Unequal Access, Unequal Outcomes: Race and Prostate Cancer

Here's the good news: The mortality rate for American Black men with prostate cancer has fallen drastically since the 1990s. Fewer than half as many who contract the disease will die from it: roughly 37 per 100,000 in 2017 compared to 70 per 100,000 in 1999. Other than a small uptick in 2007, the downward trend in the age-adjusted rate has been consistent and encouraging.

But there's a bad news component: Black men die at double the rate of non-Hispanic white men, whose mortality rate has been falling in line with that of Black men.

Despite the improvement in outcomes since the turn of the century, the cancer statistics are enough to make you do a double-take:

- Black men are 73 percent more likely than white men to be diagnosed with prostate cancer.

- Overall, Black men have more than double the risk of dying from prostate cancer—even with a low-grade type of the disease.

- Men of African descent are significantly more likely to develop low-grade cancer that is genetically predisposed to be more aggressive.

While some of the reasons for the disparities are apparent (e.g., genetics) and others are assumed (e.g., access to health care, socioeconomic inequity), ongoing research seeks to amplify the apparent and quantify the assumed.

Race and prostate cancer: A multiethnic analysis

A massive study of about a quarter of a million men led by epidemiologist Chris Haiman, Sc.D., recently shed light on some of the genetic factors that predispose Black men to such undesirable outcomes from prostate cancer. Follow-up research is going to address the other half of the equation.

Haiman's research, published in January 2021 in the journal Nature Genetics, looked at a huge trove of data from 107,247 men who had been diagnosed with prostate cancer against that of a control group of 127,006 who were cancer-free.

"Over time, we've combined smaller numbers of different ethnic groups together in some of our studies, but this is really, I think, the first very large-scale multiethnic analysis," said Haiman, a professor of preventive medicine who leads the cancer epidemiology program at the University of Southern California. "It was definitely the biggest at the time."

Aside from the sheer scope of the study, another factor that sets it apart is the way the investigators looked at men of varying genetic backgrounds.

Previous work on prostate cancer almost exclusively focused on white men. While the genetic markers for prostate cancer risk identified in these prior studies have value, they almost always fall short in predicting risk for men whose ancestry falls outside of Europe.

For perhaps the first time, Haiman and his team were able to overlay genetic data from large groups of men with European, African, Asian and Hispanic ancestry and determine not only which genetic markers were unique to each group but also which ones were common among them.

"Most genetic studies in the past, whether it be prostate cancer or other chronic diseases, have focused on populations of European ancestry," Haiman said. "And there's always the question of, 'Well, do the markers identified in that study, do they generalize? Are they transferable across populations?' And with our multiethnic study, we identified markers that work across populations."

Prostate cancer, the killer

No matter a man's ethnic background, prostate cancer is a danger. It's the second most common cancer in men and the fourth-leading cancer type overall. In the United States, prostate cancer cases make up 13.1 percent of all new cancer diagnoses.

Nearly a quarter of a million American men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2021, and some 34,000 men will lose their lives to it, according to the National Cancer Institute.

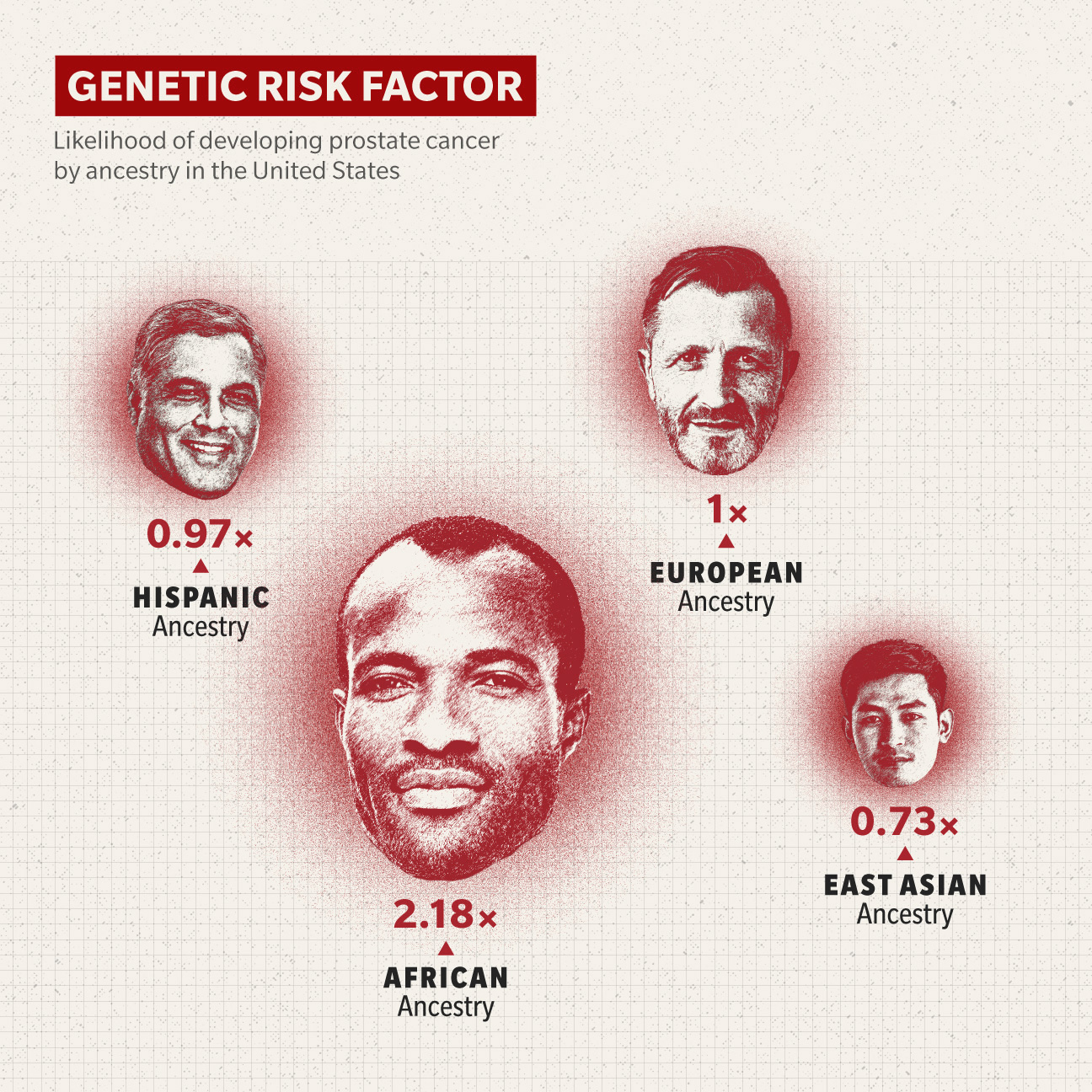

However, the numbers are grimmer for Black men. Haiman's study found the genetic risk score—basically, how likely a person is to get prostate cancer based on their DNA—for Black men is more than twice what it is for white men.

"We know there are various nongenetic risk factors for prostate cancer," Haiman said. "But there's very strong evidence that genetics plays an important role. And through this study, we identified close to 300 markers that are common in the population and can really help identify men who are at high risk and men who are at low risk of developing prostate cancer."

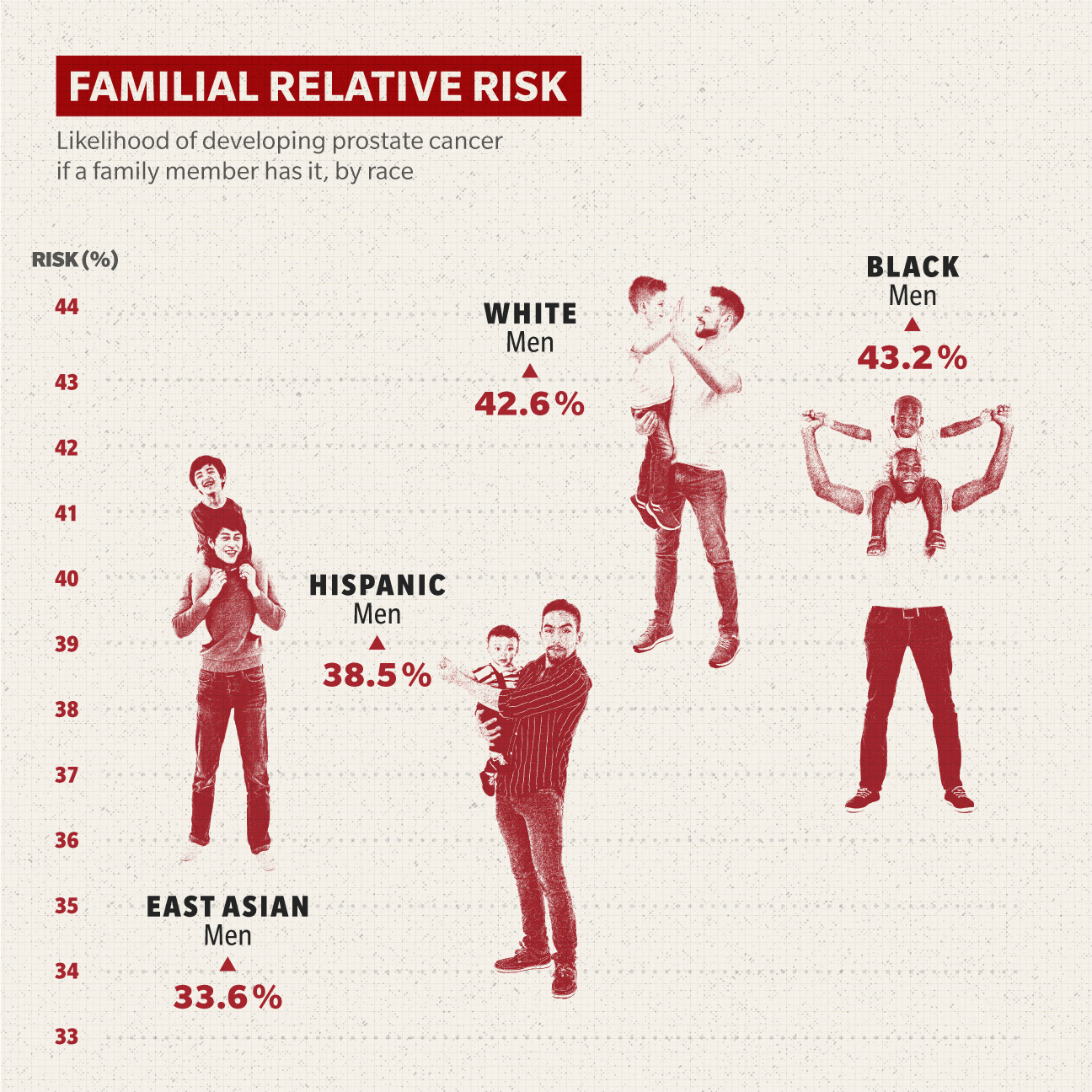

Family history makes a bigger difference for Black men, as well.

"African American men plus family history—like if they have a father or brother with prostate cancer—essentially puts them at the highest risk of developing prostate cancer," said Jayram Krishnan, M.D., a urological oncologist affiliated with the Cleveland Clinic at Akron General Hospital.

This risk is called familial relative risk (FRR), which measures a person's chance of developing a disease based on a family member having it versus the general population. This risk for Black men sits at 43.2 percent, according to Haiman's study. By contrast, East Asian men's risk increases by 33.6 percent, Hispanic men's by 38.5 percent and white men's by 42.6 percent.

If you're a Black man, you also have about a 15 percent chance of developing prostate cancer in your lifetime, as opposed to a 10 percent chance for a white man.

What's more, if a Black man gets prostate cancer, it's likely that even his early-stage cancer will be more aggressive than a white man's, according to Krishnan. Almost 6 in 10 Black men experience disease progression, in contrast to fewer than half of non-Hispanic white men, based on the 10-year cumulative incidence reported in a 2020 study published in JAMA, an American Medical Association publication.

There's a 4 percent chance prostate cancer will be lethal for a Black man, whereas a white man with prostate cancer has only a 2 percent chance of dying from it.

"If there's an African American man of the same age and the same environment as a Caucasian man and they both get prostate cancer, the African American male has a higher chance of developing aggressive cancer," Krishnan said.

The impact of access to health care

Since at least the 1950s, researchers have puzzled over these disparities in prostate cancer rates and outcomes for Black men in the U.S. versus men of European descent.

While there is clearly a genetic component, you can't sensibly talk about anything related to race in America without also addressing socioeconomic inequities.

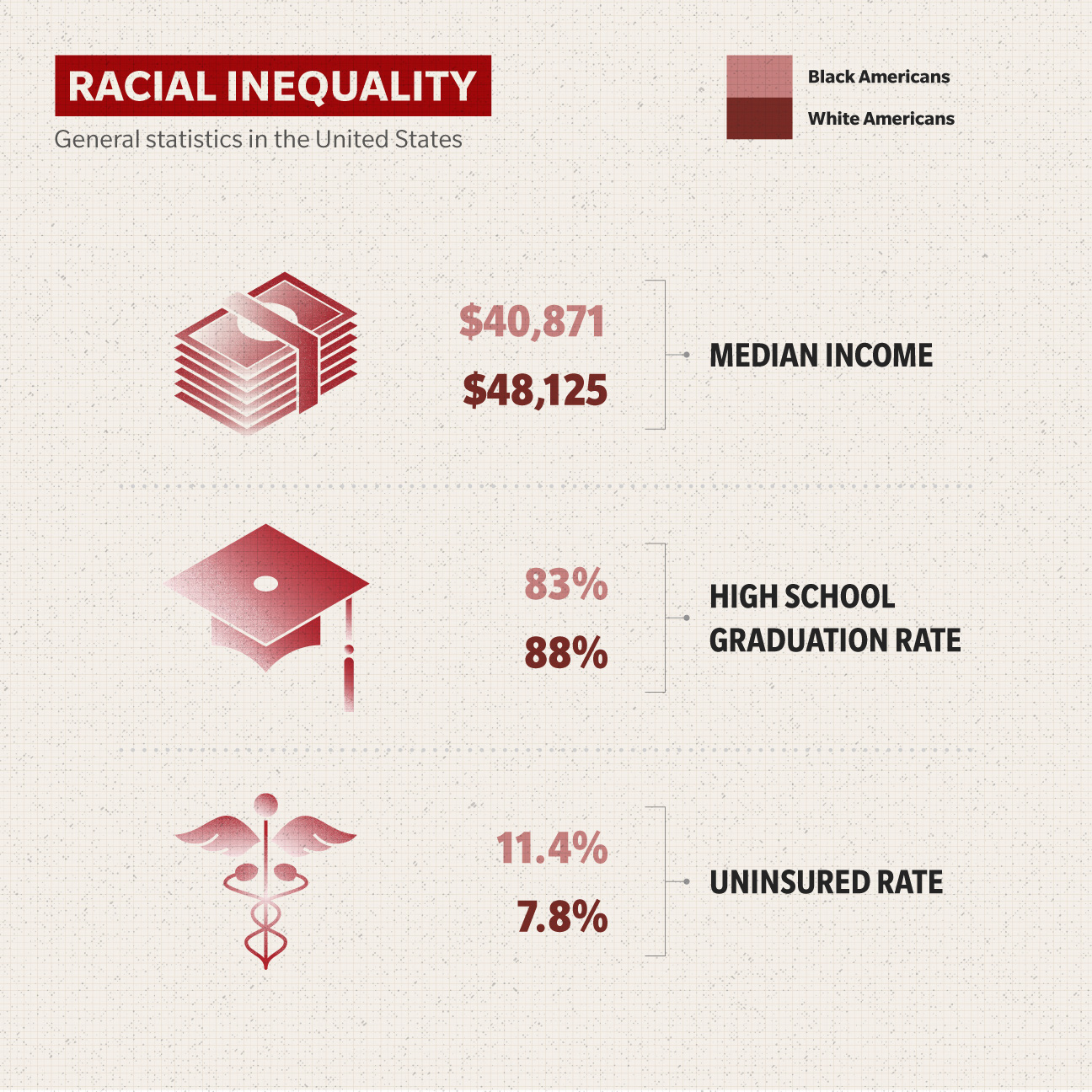

For example, one factor alone has a huge impact on prostate cancer outcomes: access to healthcare. The percentage of white, nonelderly Americans without health insurance is approximately 7.8 percent, according to data released in 2021 by the Kaiser Family Foundation. For black nonelderly Americans, the rate is 11.4 percent.

That kind of disparity inevitably has an impact on health outcomes. A 2005 study suggested that 10 percent to 30 percent of the geographic variation in prostate cancer mortality rates may be related to variations in healthcare access. In other words, less access to healthcare may contribute to more prostate cancer deaths in certain U.S. regions.

The study also found the incidence of late-stage prostate cancer is associated with geographic variations in death rates. Geographic variations in late-stage prostate cancer may account for up to 28 percent of the geographic variation in death rates for Black men.

In recent developments, prostate cancer treatment during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic was unevenly applied, according to research published in the journal JAMA Oncology. Researchers put together a retrospective cohort study that compared prostatectomy rates in Black and white men with untreated nonmetastatic prostate cancer before and during the pandemic (While also acknowledging the regionality of the study).

Given similar COVID-19 risk factors, Gleason grades (a system used to determine prostate cancer's aggressiveness) and rates of prostatectomy before the pandemic, the "data show a 90.9 percent lower rate of prostatectomies among Black patients compared with a 17.4 percent lower rate of prostatectomies among white patients."

This despite the Black men being younger, which makes them a higher priority for surgical intervention, and the established fact that Black men often have more aggressive forms of the disease.

Other recent research shows that when access to healthcare is equal, guess what—so are outcomes. Black men survive on a level comparable to white men, according to a 2020 study published in the American Cancer Society journal Cancer using data from the Veterans Affairs health system.

Location, location, location

The new research also hopes to address the effect that geographic location has on his prostate cancer risk and outcomes.

Two clusters of states have prostate cancer mortality rates among Black men higher than 41 deaths per 100,000 Black men, based on 2014–2018 data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina and Tennessee comprise one cluster, with North Carolina as the outlier, though not by much.

Oklahoma, Colorado and Nebraska make up the other area. Illinois and Hawaii (by extrapolation, as it registered only 17 such deaths) round out the 10 states that have more than 41 deaths per 100,000 Black men, and California was at exactly 41. White men in these same groups of mostly central and southern states have a much higher survival rate.

"Geography or where you live and how you are able to access guideline-based care has certainly been shown to be associated with the care cancer patients receive," said Scarlett Gomez, professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California at San Francisco. "We are collecting data from the participants on some of these access issues, whether they've had difficulty with being able to get to care, their ability to access care, to travel, in addition to insurance issues, whether that played a role in the access they received."

The next frontier

What happens now? The short answer: more work.

Haiman is one of many researchers participating in an ambitious new $26.5 million study looking specifically at aggressive prostate cancer in Black men. Called the RESPOND study, it is a sprawling, multidisciplinary research project backed by the National Cancer Institute, among others, that will expand on Haiman's previous work looking at genetic markers and incorporate social, environmental and personal history factors.

They're hoping to create a more complete picture of how and why Black men not only have higher incidence rates of prostate cancer and worse outcomes, but also why they tend to get more aggressive forms of the disease.

"The higher mortality in the population could be due to the fact that they have much greater incidence, which genetics plays a role in," Haiman said. "But there's a number of scientific projects looking at social factors, access to healthcare, social stress and tumor genetic markers, and how it may contribute to a higher incidence of aggressive disease in African American men. It's highly related to the work we've done in the past, but it adds many other dimensions to it."

In addition to recruiting one of the largest cohorts of Black men with prostate cancer ever assembled, the RESPOND study is also covering a lot of ground—literally. Researchers are recruiting from eight states, adding more diversity to the data.

"There are so many studies out there in the cancer space where you see people studying genetics or studying social determinants," said Gomez, who is leading the social stressors component of the RESPOND study. "But really pulling it together in one study is few and far between. The idea is doing a really comprehensive 'cells to society' study."

To Gomez's point, it's important to know that the median age for prostate cancer diagnosis is 63 among Black men and 66 for non-Hispanic white men—and that based on the VA study. Black men are more likely to live in regions where they have a nearly 20 percent lower median income ($40,871) than white men ($48,125), and lower high school graduation rates by 5 percentage points—83 percent for Black men and 88 percent for white men.

That's all good information. But what do all of those facts mean together? We may know soon enough.

The RESPOND study isn't the first of this type of "convergence epidemiology" research, but according to Haiman, it may be the largest in terms of looking at prostate cancer in Black men.

"It's the scale of the study," Haiman said. "Individual studies people have done in African American men, even if they're genetic studies, have been able to recruit no greater than, like, 1,000 [participants]. But this one study alone will probably be able to recruit at least 10,000 men."

Gomez points to the ways that a lifetime of experiencing systemic racism—with accumulated emotional, mental and physical injuries—can contribute to poor health outcomes, including having an influence on whether a man develops prostate cancer.

"We know cancer doesn't just happen," she said. "It's an accumulation of genetic mutations that happen over a lifetime; a breakdown in immunity. We're using more established survey tool items that capture experiences with certain types of discrimination; more day-to-day kinds of experiences that reflect the bias due to somebody's race, but also major types of life experiences, like have you ever been unfairly stopped by police or unfairly fired from a job."

Getting ahead of prostate cancer

The hope with the new research is that it will allow men to better understand their risk of prostate cancer.

Armed with the type of genetic background information being assembled by Haiman and his team, men would be able to consult their physicians well before they reach the point of diagnosis. After all, if current prostate screening is "successful," it only tells you how far the condition has progressed.

"The PSA [prostate-specific antigen test] is for after you have prostate cancer," Krishnan said. "Now, we're taking it a step back. The genetic aspect is going to be another way to derive your probability of developing prostate cancer."

Indeed, based on genetic work like Haiman is undertaking, Krishnan can envision a world where urological oncologists such as himself are put out of business. He can imagine the end of prostate cancer because it would never be permitted to develop in the first place.

"If you have the high-risk genes for breast cancer, you go ahead and do a prophylactic mastectomy," Krishnan said. "So I can see somewhere in the future, if we're able to derive a probability of a patient having prostate cancer, I could see the patient having the prostate removed prophylactically. I could see that happening within 10 to 20 years."

Krishnan was quick to point out that, thanks to advances in prostatectomy surgery in the past decade or so, there's almost zero effect on men's sexual or urinary function anymore after having the prostate removed.

Haiman hopes the genetic data produced from his work can give patients and their doctors more pieces of the puzzle.

"It's more information," Haiman said. "In addition to one's age, family history, and race and ethnicity, it can be used to make better decisions as to how to proceed when getting a PSA test at 50, or even 45 or 60 or 65, because of your risk."