Transgender Women Can Get Prostate Cancer, Too

Health care for transgender people is similar to a larger societal view on trans issues: We've made a lot of progress, but more is necessary.

Much more.

Trans women in particular face unique risks regarding prostate health, especially with cancer screening and treatment.

But what are those challenges and how is the medical community evolving to offer better care?

Trans women and prostate cancer screening

For starters, screening for prostate cancer in trans women involves paying attention to the same risk factors, such as age, race and family history, facing a cisgender man.

If they haven't undergone gender-affirming hormone therapy or gender-affirming genital surgery, a trans woman's prostate gland presents similarly to that of a cis man. Screening for these patients would likely follow the typical flowchart: prostate-specific antigen (PSA) tests leading to secondary testing if indicated, then a potential biopsy.

However, all of this changes if the person is on gender-affirming hormone therapy, which suppresses the production of testosterone.

"Their normal PSA values are not going to be the same as someone who is not on several years of hormone suppression," said Amy Pearlman, M.D., a urologist and the director of men's health at the Carver College of Medicine at University of Iowa Health Care. "So unless someone who is checking their PSA is aware that those reference ranges are going to be different, they may not even detect that the person has an elevated PSA for the medications that they're on."

If they haven't undergone gender-affirming hormone therapy or gender-affirming genital surgery, a trans woman's prostate gland presents similarly to that of a cis man.

PSA is a protein made by both normal and cancerous cells in the prostate gland. The PSA threshold for a person who isn't on hormone suppression is usually about 4.0 nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL) of blood. Depending on a person's age and other factors, the level can fluctuate up or down, and values higher than about 4.0 could indicate serious problems, which would mean further testing.

However, for a trans woman on testosterone suppression therapy, the cutoff point is just 1.0 ng/mL—a critical difference.

"If they're on gender-affirming hormone therapy, practitioners and patients both need to realize that a PSA cutoff of 4.0 in the trans community is not appropriate," said Brian K. McNeil, M.D., the chief of urology at the University Hospital of Brooklyn in New York City. "It's lower if you're accounting for the impact of hormones."

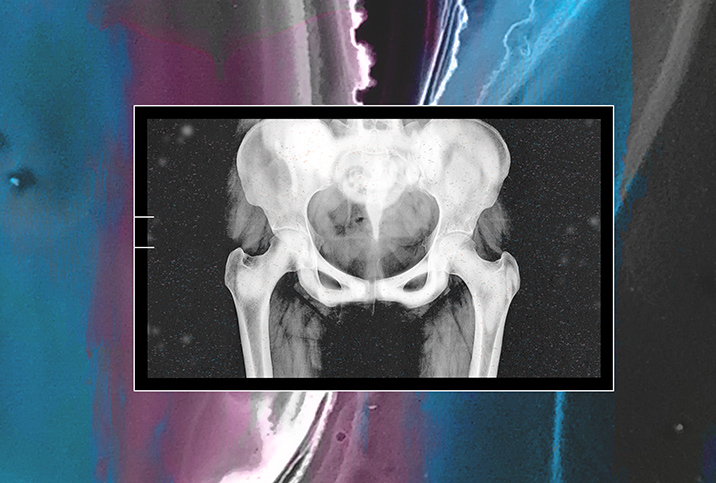

Trans women and prostate size

Another consideration is that testosterone suppression therapy shrinks the size of the prostate gland. Similar hormone therapy is often used in combination with radiation for men who have metastatic or otherwise high-risk prostate cancer to do just that.

However, for a trans woman facing a prostate cancer diagnosis, testosterone suppression can throw a monkey wrench into things.

"It makes the prostate really small, and operating to remove a really small prostate can be very difficult," Pearlman said. "It can still be irradiated, so that would probably be similar; I don't know if there's any difference for a really small prostate versus a larger one for irradiation. But then in terms of even getting a biopsy for diagnosis, it'll depend on whether they've had surgery."

The good news for a trans woman who has undergone gender-affirming bottom surgery is the prostate is relatively easy to access for a biopsy through the vagina, as the prostate sits directly up against it.

The bad news for those with a cancer diagnosis is that apart from the difficulty of operating on a hormone-shrunken prostate, removing the prostate can cause even more complications than it would in cis men or trans women who haven't had bottom surgery.

"To remove the prostate after that, they might actually leak a lot of urine," Pearlman said. "That's why we don't generally remove the prostate at the time of gender-affirming genital surgery, because we're dissecting through pelvic floor muscles, and so they become reliant on the sphincter between the bladder and the prostate. If we remove the prostate, we remove that sphincter that's keeping them dry and they can actually become incontinent."

Trans women and special screening

The PSA test has its limitations for trans women and cis men alike. One possible remedy in the case of trans women might be expanded use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) tests.

"With members of the trans community, the PSA test is not as reliable," McNeil explained. "We're using an imperfect test that's made even more imperfect by someone being on gender-affirming hormone therapy. I think in the future—and this hasn't really been studied yet—but in the future, we might have to rely on the use of MRI more to detect prostate cancer. MRI can help us discern whether or not there's some sort of lesion present in the prostate that's concerning. It's not a perfect system, but it helps."

Conclusions

In terms of providing health care for trans people in general, good clinicians are becoming more aware of the approach to treating patients of all kinds.

"Patients who identify as gender-expansive are going to show up at any one of our clinics, and it may not be specifically for gender-affirming genital surgery," Pearlman said. "These patients will have concerns or healthcare questions about any part of their body. Every single healthcare provider has to feel comfortable providing culturally sensitive care. They might need to see other people in other clinics who routinely do oncology and who don't routinely see transgender patients. These providers need to get comfortable with the conversation, so these patients who need care are comfortable coming in.

"Otherwise, if we don't make it comfortable for them, we can't be surprised if they don't show up at our clinics," she added.