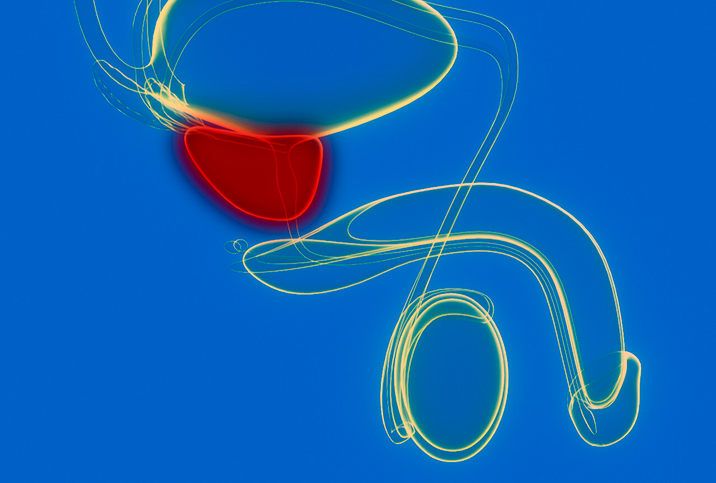

Prostate Cancer Patients May See Benefits From Combination Therapy

Discussions about treating cancer often fall into three distinct silos: surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy.

Prostate cancer patients, though, may not be as familiar with another treatment category called combination therapy, a process that combines radiation with hormonal therapy.

Also known as androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), hormonal therapy involves suppressing androgens—sex hormones such as testosterone—to starve the cancer of the fuel it needs to grow.

Combination therapy, also known as multimodal therapy, has long been an option for patients whose cancer has expanded outside of the prostate or is considered high risk due to other clinical findings.

Now, thanks to the publication of a new meta-analysis, clinicians are gaining insight into how combination therapy can be more effectively calibrated for men in high-risk categories as well as those with intermediate-risk prostate cancer.

The research

As the second deadliest and most common type of cancer for men—only skin cancer is more prevalent, according to the American Cancer Society—prostate cancer has been extensively researched in the modern era. But a breakthrough meta-analysis published in January 2022 in the Lancet Oncology looked at nearly 60 years of large combination therapy trials from around the world and synthesized the relevant results in a way that offered some powerful new insights.

"We sought out every single randomized trial that had been done with prostate cancer patients getting radiation, with or without or variable durations of hormone therapy, in what we call Phase III trials—big, randomized trials in multiple centers, not just one institution," said Daniel E. Spratt, M.D., the study's lead author and the Vincent K. Smith chair in radiation oncology at University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center in Cleveland. "And they had to report on what we call long-term or hard end points, like developing metastatic disease or how long you live. They can't just report on, like, patients' PSA response levels."

The questions

Spratt and his colleagues approached the data from 12 relevant trials with three queries:

- What is the benefit of adding hormonal therapy to radiation therapy?

- What is the benefit of adding hormonal therapy before beginning the radiation treatment (aka neoadjuvant therapy) and/or prolonging it?

- What is the benefit of adding hormonal therapy after radiation treatments (aka adjuvant therapy)?

With regard to the first question, the research seemed to confirm that by incorporating hormonal therapy, the effectiveness of radiation therapy was dramatically improved.

"Adding hormone therapy, we showed, for patients with what's called 'intermediate-risk prostate cancer' and 'high-risk prostate cancer,' there's a very profound improvement in reducing the development of metastatic disease and also in how long they live," Spratt said. "You treat on the order of about 10 men, and you prevent one man from either dying or developing metastatic disease 10 years later. So it's pretty profound."

The study also suggested when to include hormonal therapy. For the first time, findings from the meta-analysis showed that adding hormonal therapy for an extended period prior to radiation therapy appears to have no effect one way or the other.

"In the past, some people may say, 'I'll give you hormone therapy for three months before starting radiation,'" said Brian K. McNeil, M.D., the chief of urology at the University Hospital of Brooklyn in New York City. "Some people might have thought that if you manage someone with hormones before starting radiation, that could have an impact on their overall survival or metastasis-free survival. Looking at all these old studies, these randomized trials, [Spratt's study] has shown that it doesn't make a difference. You can start them both at the same time."

How do you create hormones?

Since the body's testosterone production is being curtailed during the process of ADT, the patient may suffer many of the side effects of low testosterone. It can affect libido, mood, energy and erectile function—all the same symptoms touted in those late-night ads for powders and pills that don't have approval from the Food and Drug Administration.

Out of deference to patients' concerns about their post-treatment sex life, clinicians may steer men away from combination therapy and recommend higher radiation doses instead.

The data shows this approach may not be as effective.

"Unfortunately, there are a lot of practitioners out there who, if you give them a hammer, everything's a nail," Spratt said. "So if I'm a radiation doc, [I] just ignore hormones: 'No guy wants to be on hormones. Let me just blast away with the radiation.' But there's a pretty profound benefit [to hormonal therapy] no matter what radiation dose you give. The most important components are giving the hormone therapy during the radiation and probably following the radiation therapy."

Encouragingly, once the combination treatment is complete, the patient's original testosterone level may be recovered.

"The hormone manipulation we do lasts for a certain amount of time," McNeil said. "We alter the pathway through which your body produces testosterone. But once those medicines wear away, the hope is that your testosterone production will ramp back up. So, fingers crossed, it can come back."

Conclusions

The good news is that even older data on prostate cancer still has valuable information to offer dedicated researchers like Spratt and his team. Lives will be saved, and more men can enjoy metastases-free lives because of what researchers are still gleaning from long-concluded trials.

For people whose lives have been touched by prostate cancer in a personal way—people like McNeil—what we know and when we know it can make all the difference.

"My father was actually diagnosed with prostate cancer and he died from it when I was about 15 years old," McNeil said. "The things we know now about hormone therapy and radiation and whatnot, we didn't have the same knowledge then. So this study, I think, is pretty important because it tells us that giving androgen deprivation therapy along with radiation really works."

According to Spratt, the key development is that men and their healthcare providers now have better information with which to work.

"I think the big takeaway is that in most cancers, what we call multimodality therapy usually results in the best outcomes, and that we've provided evidence in this study for practitioners," he said. "But hopefully, they can provide to patients very personalized estimates to what's the benefit of adding these various hormone strategies."