What Is the Freeze Response to Trauma?

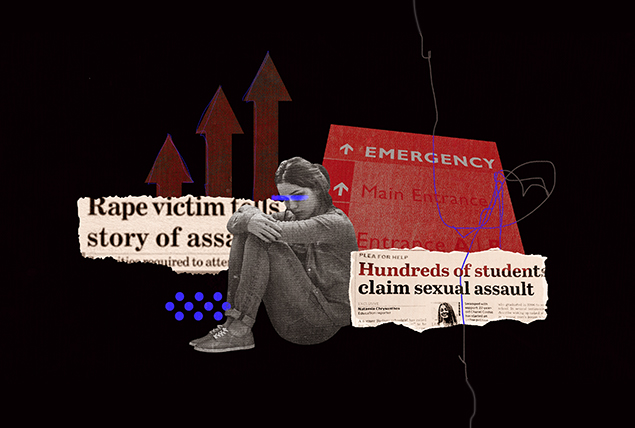

In sexual assault cases, it's not uncommon for the court of public opinion—and defense attorneys—to argue that if the victim didn't fight hard enough, scream loud enough or run away fast enough, they must have wanted it.

Even in assault prevention education, many students are taught that "fight or flight" are the "right" ways to respond to threats. But these options aren't always available.

Research suggests about 70 percent of sexual assault survivors experience a third response known as freezing, according to Rebecca Heiss, Ph.D., an evolutionary biologist and stress physiologist based in Greenville, South Carolina.

What does it mean to have a freeze response?

Like the fight-or-flight response, the freeze response is an evolutionary, automatic function that has helped humans survive for thousands of years, Heiss said. However, despite its prevalence, many people are unaware it exists.

As a result, survivors often feel ashamed and blame themselves, believing they could or should have done more to prevent the assault. Not only can this compound the trauma and inhibit healing, but it can increase people's susceptibility to chronic mental health issues.

These health issues include post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which is 2.75 times more likely to affect women who freeze in response to trauma, a 2017 study suggested.

What is the freeze response?

The nervous system consists of two main parts:

- Somatic nervous system. It handles voluntary, conscious actions, such as walking or speaking.

- Autonomic nervous system (ANS). This system performs essential functions to keep you alive, such as breathing and responding to stress.

Fight mode, flight and freeze all stem from the ANS and are involuntary, reflexive adaptations for survival and how our body responds to perceived danger.

The freeze response, specifically, usually occurs when the threat seems so imminent and overpowering that fighting or fleeing seems impossible and potentially lethal, Heiss explained.

"It shuts us down, essentially. If you've ever seen a possum play dead, it's the same kind of immobility," she said.

The response occurs on a spectrum, with various manifestations and severity levels, she said, from complete tonic immobility (temporary paralysis), where the brain disassociates from the body to a "grin and bear it" phase.

Other than tonic immobility and disassociation, symptoms may include the following, according to the nonprofit organization Ashley Addiction Treatment and a 2007 study:

- Feeling disconnected

- A 'deer in headlights' sensation

- Restricted breathing

- Feeling cold or numb

This response can occur with various forms of trauma, but Heiss said the freeze response had been studied primarily in relation to sexual assault and sexual trauma.

"Really, freezing is an escape from a more dominant member of society," she said. "For example, if you think of rich celebrities or leaders—anybody that has power—the freeze response is the mechanism to basically say, 'OK, you're bigger than I am. You have more pull. There's nothing that I can do here. If I run away, you can catch me. If I try and fight back, you know you're larger than I am and it's going to cause harm to myself either psychologically or physically.'"

Experts said the functional freeze response could also occur before fight-or-flight, serving as a temporary "pause" while the ANS assesses the threat and determines the best course of action.

As for why the disassociation freeze response can be conducive to survival, Heiss explained it protects the body and psyche from going into "complete overdrive." Dissociating basically removes all responsibility for everything that's happening in the moment. Sometimes, what's happening can be so overwhelming and traumatic that the mind can't process what's happening to the body.

"With that kind of tonic immobility, we stop feeling our bodies, which, again, in these incredibly traumatic situations, that's an adaptive response. You don't want to be feeling what's happening. You don't want to have to be processing that in the moment because it would be too painful, too much for the body to take," Heiss added.

How does the freeze response compare to fight-or-flight?

Both fight and flight produce a state of hyperarousal, where your heart rate, blood pressure and breathing rate all accelerate to prepare you for escape or confrontation, according to Ellen Astrachan-Fletcher, Ph.D., a regional clinical director at Pathlight Mood and Anxiety Center in Chicago.

Fight typically entails a form of power-seeking and aggression, which can involve physical, verbal or other forms of attack. The latter can include actions such as writing scathing comments online, said Susan Zimmerman, L.M.F.T., a certified clinical trauma professional based in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area.

Flight involves trying to evade danger altogether. Like freezing, these are automatic responses to real or perceived threats or stressful circumstances, according to Erika Rajo, Psy.D., a trauma psychologist and director at the University Medical Center New Orleans Trauma Recovery Center.

"When the stress response is activated, the part of your brain responsible for logical thinking goes offline temporarily, allowing the emotional processing center (amygdala and hypothalamus) to take charge," Rajo said. "Your emotional brain tells the rest of your body what to do to maximize your chance of survival in the current situation."

As Heiss said, when fighting or fleeing aren't viable options, the freeze response typically takes over.

What is the fawning trauma response?

There is a fourth even lesser-known response. The fawning trauma response involves attempting to appease or please others to protect yourself from harm, according to Hayley Nelson, Ph.D., a neuroscientist, psychology professor and founder of the Academy of Cognitive and Behavioral Neuroscience (ACBN) in the Philadelphia area.

Behaviors associated with fawning include trying to "win over" someone with compliments, special attention, services or expressions of affection to evade danger, Zimmerman said.

"The purpose of this 'people-pleasing' is to 'keep the peace' and regain a sense of safety," Rajo said. "As with other trauma responses, a person might develop the fawning response as a means of survival in one stressful environment or unhealthy relationship and reflexively deploy this defense mechanism later in situations where it isn't warranted and/or does not benefit them."

Note, however, that a person doesn't choose to fawn anymore than they choose to freeze under pressure, Rajo added.

Can you experience chronic freeze responses?

It is possible to become stuck in a freeze response, experts said. The phenomenon is more prevalent in people with PTSD or complex PTSD, but anyone who has repeatedly experienced trauma or intense stress can develop it.

"One of the sayings we have in neurobiology is 'neurons that fire together wire together.' That means the more often you experience something, the more often those neurons fire together, the more likely they will do the same behaviors in the future," Heiss said. "So if you freeze the first time and you survive—which in biology, that's all that matters—then your brain records this and says, 'Ah, great, that worked. I'm going to do that again next time and next time and next time.'"

This doesn't only happen in response to acute threats but to reminders of the trauma, too, Nelson and Astrachan-Fletcher said. In people with PTSD, chronic freeze responses often occur alongside flashbacks and involve disassociation, Astrachan–Fletcher explained.

Similarly, the nervous system can be stuck in a fight-or-flight response. Besides PTSD and CPTSD, this can be symptomatic of—and contribute to—various conditions, including anxiety and depression, according to Mayo Clinic.

What are the chronic freeze response symptoms?

Experts said several chronic freeze response symptoms resemble those of a one-time freeze response and share similarities with PTSD.

These responses include, but aren't limited to, the following:

- A habit of maintaining silence or quietude when interacting with a perceived dangerous person or persons

- Avoiding situations where there's a perception of possible danger, even social situations

- Emotional numbness

- Physical immobilization

- Feeling like a deer in headlights

- Feeling physically tense or rigid

- An exaggerated startle response

- Tunnel vision

- Dissociation

- Trouble communicating

- Being on edge

- Regularly scanning for threats, even in benign situations

A chronically overactive stress response can have several consequences for physical and mental health, Rajo said. Additionally, if people are repeatedly traumatized or in stressful situations in childhood, their brain's development can be affected, predisposing them to conditions such as anxiety and panic disorders.

How can you overcome the freeze response?

As for how to get out of a freeze response, it's impossible at the moment, Heiss said, emphasizing again that it's completely involuntary.

"Often, women go back and they blame themselves. They're like, 'Oh, I should have run, I should have screamed, I should have done this or that,'" she said. "The reality is, you can't. You cannot override this mechanism in the moment."

That said, she continued, there are ways to move from PTSD to "post-traumatic growth," or PTG, which largely involves training the brain to operate differently in moments of stress.

"So you can train ahead of time and you can train after the event, so that you're less likely to respond the same way in the future," Heiss said.

Long-term techniques to overcome the freeze response include trauma-focused therapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) and somatic experiencing (such as deep breathing and mindfulness), Rajo and Nelson said.

"These therapies aim to address underlying trauma, promote self-regulation skills and help individuals develop new coping mechanisms," Nelson said.

The bottom line

Experts said the most important thing for survivors to recognize is that freezing is natural, adaptive and involuntary. It may feel as though your body is betraying you, but it is a subconscious biological response you had no control over—and it is not your fault, Heiss reiterated.

"We spend an exorbitant amount of time trying to educate women on what to do during a sexual assault. And the reality is they can't do any of it because their body is taken over by these physiological mechanisms," Heiss said.

"You did not choose to freeze. The freeze response is involuntary. Freezing helped you survive," Rajo said. "Your brain and body helped you do exactly what you needed to do to survive. You are not to blame, and you are not broken."

If you are a trauma survivor, experts advise seeking help from a qualified healthcare provider who specializes in trauma, stress responses and PTSD. Although the freeze response is uncontrollable, it is possible to heal, adapt and move forward with support and professional guidance.