What Is the Link Between Sexuality and Mental Health?

Sexuality and mental health are inseparable. Both can impact a person's overall health, well-being and quality of life.

"The World Health Organization (WHO) defines sexual health as experiencing optimal, consensual, pleasurable sexual experiences, going beyond just the absence of disease. It includes physical, emotional and mental components, relating it directly to mental health," said Candice Nicole Hargons, Ph.D., an associate professor at the University of Kentucky and executive director of the Center for Healing Racial Trauma in Louisville, Kentucky.

"That means people who are mentally healthy are less likely to experience decreased sexual health," she added.

Similarly, WHO defines mental health as a "complex continuum" distinct to each individual. More than an absence of psychiatric disorder, it is a state of mental well-being that allows a person to cope with life stressors, realize their abilities, learn and work well, and contribute to their community.

"It is an integral component of health and well-being that underpins our individual and collective abilities to make decisions, build relationships and shape the world we live in," states the WHO website. "Mental health is a basic human right. And it is crucial to personal, community, and socio-economic development."

Sexuality and mental health can influence one another, according to Sara C. Flowers, Ph.D., the vice president of education and training at Planned Parenthood Federation of America, headquartered in New York City.

For example, masturbation and sex can produce mental health benefits, including improved mood, reduced stress and better sleep.

Conversely, stigma and shame around bodies, sex, sexuality and relationships can adversely impact mental health.

Mental health conditions, which impact about half the United States population to some degree, can have sexual health implications, too.

Sexual and mental health are integral to public health, Flowers noted, and prioritizing them as such could have extensive, meaningful impacts.

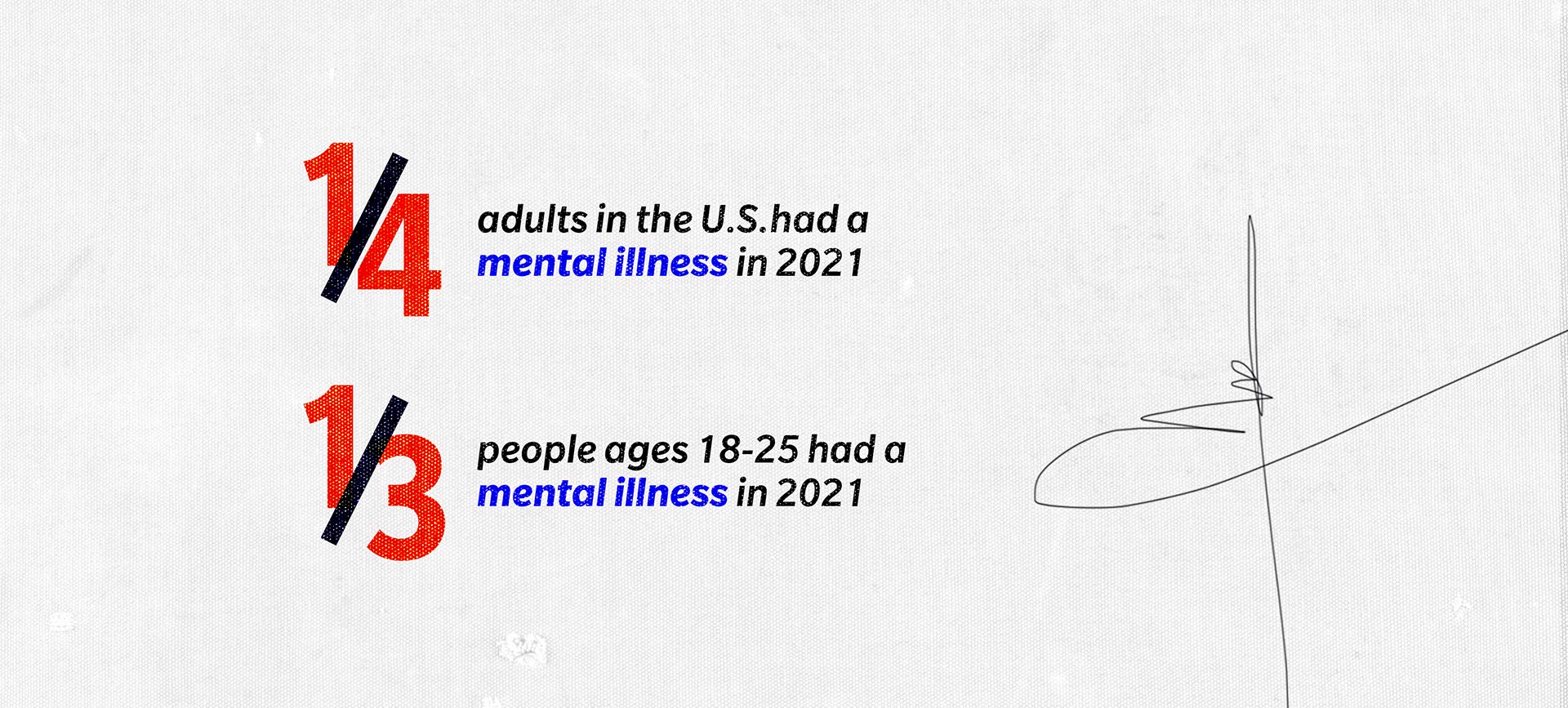

About one in four adults in the U.S.—and one in three people ages 18-25—had a mental illness in 2021, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration annual survey published by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HSS).

That's compared to 20.78 percent of adults in 2019-2020, as published in the annual State of Mental Health Report by Mental Health America.

Approximately 1 in 25 adults in the U.S., or 10 million people, live with a serious mental illness, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). A serious mental illness is defined as causing substantial functional impairment and severely limiting one or more major life activities, per the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

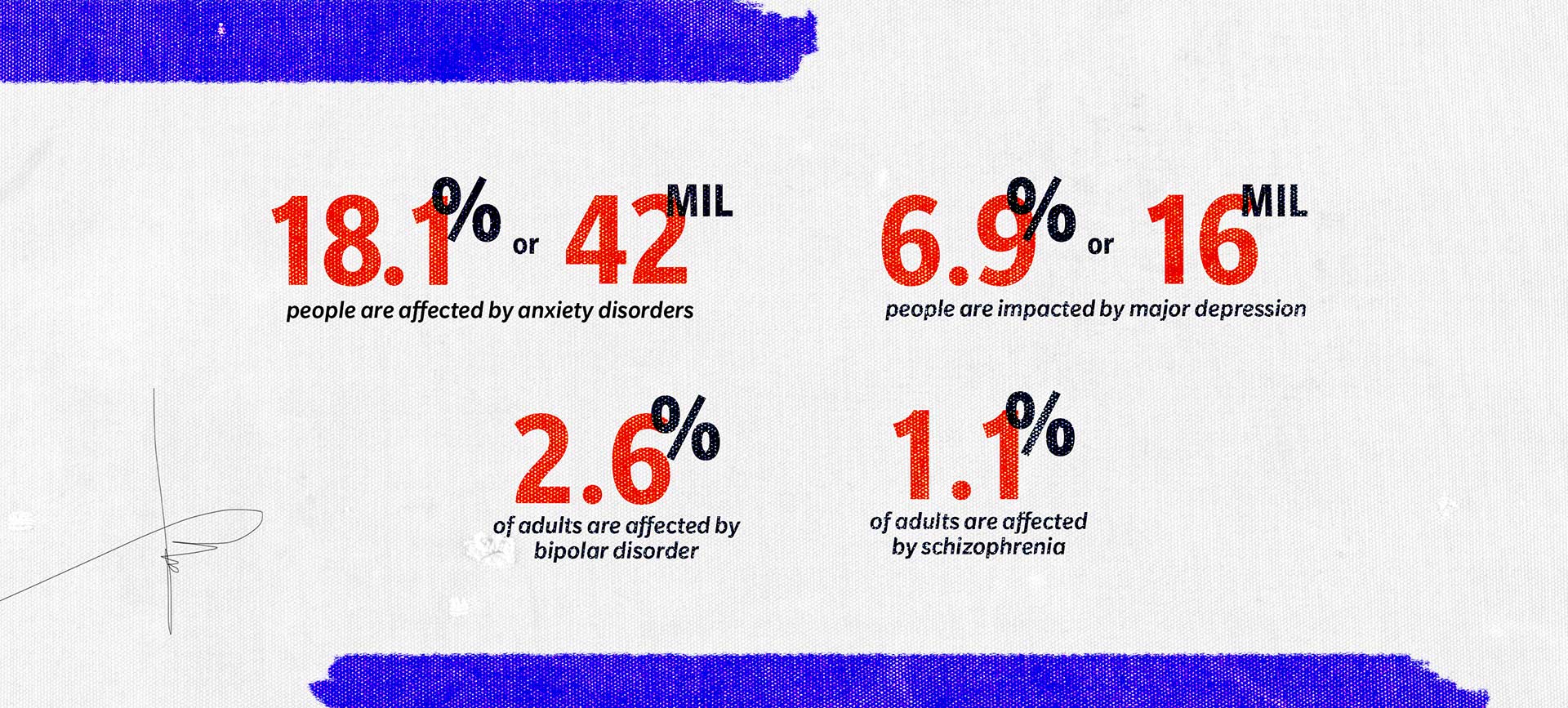

According to NAMI, anxiety disorders are among the most prevalent, affecting about 18.1 percent of U.S. adults, or 42 million people. Major depression impacts 6.9 percent of adults, or 16 million people, while bipolar disorder affects about 2.6 percent of adults, and schizophrenia affects 1.1 percent of adults.

Millions more people experience symptoms of mental illness, even if they don't meet the full diagnostic criteria. According to the U.S. Census Bureau's Household Pulse Survey of 2020-2023, 47 percent of adults reported anxiety symptoms and 39 percent disclosed symptoms of depression.

More than 20 million Americans ages 12 and over meet the criteria for substance use disorder, and about 10 percent of American adults will have a substance use disorder at some point in their lives. Federal agencies have reported this number has risen dramatically since the 1990s, due largely to the ubiquity and addictiveness of opioids, including fentanyl.

The National Center for Drug Abuse Statistics has deemed the opioid epidemic a "public health emergency." The number of opioid-related overdose deaths jumped from 70,029 in 2020 to 80,816 in 2021, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Although the COVID-19 pandemic spurred mental illness in many who'd not previously experienced it and exacerbated symptoms in those with existing conditions, the nation was in a mental health crisis well before 2020.

Tameca N. Harris-Jackson, Ph.D., L.C.S.W., is a sex and relationship therapist, intimacy and relationship coach, and founder and director at Hope and Serenity Health Services in Altamonte Springs, Florida.

She asserts that many factors have contributed to a slide in mental health, including a changing political climate, environmental crisis, the health effects of certain environmental toxins and an economic downturn.

"We've had a lot of ways and reasons over the past several decades where people have started to feel they're no longer safe in their bodies, in their homes or in their communities. They no longer feel like they can take care of themselves, their families. It's really been having an impact," Harris-Jackson said.

Despite the life-altering consequences of untreated mental illness, about half of people with mental health concerns generally—and 94 percent of those with substance use disorders—didn't receive any treatment in 2021.

This is largely because of inadequate resources due to insufficient public services and flawed insurance policies that left patients and providers in the lurch, she said.

"The reimbursement rates are much lower for mental health. And because of that, and with the influx and the need, many providers are saying they're having the same issues as well that their clients are having, especially trying to take care of themselves," she explained.

As a result, she said, providers are leaving insurance networks and practicing privately, making their services inaccessible to people who cannot pay out of pocket.

More than 150 million people live in federally designated mental health shortage areas, and more than 50 percent of counties nationwide have no psychiatrists, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC).

The AAMC predicts that, within a few years, the country will be short between 14,280 and 31,109 psychiatrists, while other mental health care providers will remain overextended.

There's also a stark shortage in inpatient care facilities.

In response to public outcry over widespread abuse and neglect, and advancements in psychological research, scores of psychiatric facilities shuttered in the 1950s and 1960s. The well-intentioned strategy yielded some significant positive outcomes, and many patients flourished in their newfound freedom with community-based support.

However, many of those most seriously ill were left destitute.

During the civil rights movement, efforts to expand community mental health services helped fill the gap, but a significant population requiring inpatient care remained without access. Despite noteworthy advancements, the problem persists.

According to a 2012 report by the Treatment Advocacy Center, a nonprofit that works to improve treatment access for people with mental illness, the number of inpatient psychiatric beds decreased by 14 percent from 2005 to 2010. Currently, there are more people with mental health conditions in prisons than in hospitals.

Exacerbating barriers to care, Medicaid doesn't pay for long-term institutional treatment in facilities with more than 16 beds. Also, public hospitals typically can't keep patients for more than 72 hours due to insufficient resources.

Many private psychiatric hospitals and inpatient rehabilitation facilities don't accept insurance, and a weeklong stay could cost several thousand dollars.

As for why there's such a stark contrast in resources and reimbursement rates for mental versus physical care, Harris-Jackson pointed to a historical lack of awareness of the importance of mental health and its place in public health.

"We didn't put that same priority on mental health the way we did on physical health. It was almost like if you couldn't see it, you couldn't treat it. We know better now, but the policies have not caught up with the devastation that we're seeing," she said. "We're in a severe crisis, and I don't think there are many mental health providers you can speak to that wouldn't say the same thing."

There are more people with mental health conditions in prisons than in hospitals.

Alongside the opioid epidemic, the U.S. is experiencing an epidemic of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

As of 2018, about 20 percent of the U.S. population had an STI on any given day, according to the CDC. The COVID-19 pandemic, with its effect on testing and services, exacerbated the plight, and incidence rates continue to climb.

In addition to the physical consequences, if STDs are left untreated, they can lead to severe mental health complications.

Syphilis, for example, can cause psychiatric symptoms such as depression, delirium, mania and psychosis. However, STDs and STIs primarily impact mental health through the stigma and shame associated with them, noted Hargons.

"People who have STIs, regardless of chronicity, fear disclosure because a valence of disgust often accompanies those types of infections or diseases," Hargons said. "This is largely due to sexual shaming and sex-negative views, as we don't typically maintain a similar level of disgust for people who disclose a cancer diagnosis."

The stigma around sex and sexual health conditions can stem from multiple sources, including cultural and religious beliefs, upbringing, past experiences, and stories and messages delivered by others. Flowers noted that, in the end, this negative perception harms everyone—regardless of STI status.

Despite the ubiquitous nature of STIs and the fact that so many Americans will, at some point in their lives, be infected, the stigma still leads people to feel dirty, ashamed and isolated, Flowers added.

As a result, individuals may be reluctant to seek and utilize prevention, testing and treatment services that could preserve or improve their health and protect others.

"Stigma doesn't prevent STIs. In fact, the stigma around STIs can increase our shame related to sex and sexuality and result in not getting tested regularly, not talking to our partners about our sexual health history and more," Flowers explained. "Those stigma-fueled behaviors can, in turn, increase our risk of getting or spreading an STI."

Even taking a pregnancy test can elicit a slew of emotions, including stress, depression or anxiety, regardless of whether the pregnancy was planned or unplanned, and as pregnancy hormones intensify, so too can emotional and psychological changes.

As a result, people are at increased risk of the onset and relapse of mental health disorders during the pregnancy and postpartum period, according to Rachel Diamond, Ph.D., L.M.F.T., clinical training director and assistant professor for couple and family therapy programs at Adler University in Chicago.

Diamond suggested examining pregnancy through a biopsychosocial (BPS) lens since biological, psychological and social health domains are all interconnected, and each affects a person's mental health.

"Psychologically, there is immense stress and anxiety related to the major life transition that is pregnancy, in addition to incredible changes to one's identity," Diamond explained. "Lastly, the social domain of health considers the relationships and conditions of one's environment. If either of these is negative—for example, poor or limited relationships or limited resources—it can have a negative impact on the other domains of health."

Although a certain degree of stress and anxiety are expected during pregnancy, and "baby blues" are common in the days following birth, these typically dissipate soon after the baby arrives. However, about 1 in 7 birthing people experience a more severe disorder, postpartum depression, which can persist for months without intervention.

Postpartum psychosis (PPP), a rarer and more severe condition requiring immediate medical attention, occurs in approximately 1 in 1000 births, Diamond added. About 40 percent to 50 percent of people with PPP have no history of psychiatric disorders, and the only apparent risk factor is giving birth for the first time.

"It's thought that the incredible hormone changes that occur immediately after birth places the person at psychiatric vulnerability, which is why this disorder also tends to have a sudden onset, one to two weeks after birth," she explained.

As well as the factors mentioned above, Diamond added that societal messages and myths around motherhood that establish the concept of a "good mother" can be incredibly detrimental to mental health.

Moreover, the shame and stigma around emotional and psychiatric challenges in motherhood can also be barriers to getting the right mental health diagnosis and treatment.

"When 1 in 5 new mothers develop perinatal mood and anxiety disorders, it's no wonder a common experience is to question themselves and ask if they are, in fact, good enough," she said. "Rather than see themselves as having a curable disorder largely created by biological factors and unrealistic societal structures outside their control, they turn the blame inwards."

Infertility, miscarriages and stillbirths also carry substantial mental health consequences, Diamond added.

Research indicates that people dealing with infertility report similar levels of depression as those diagnosed with chronic, life-threatening illnesses like cancer. Miscarriage and stillbirth can spur equally significant and life-altering distress that can persist for years.

More than 150 million people live in federally designated mental health shortage areas, and more than 50 percent of counties nationwide have no psychiatrists.

"When we are physically and emotionally safe, we may feel freer to be our authentic selves, to try new things and to be more vulnerable and build better intimacy in our relationships," Flowers explained. "On the other hand, feeling physically or emotionally unsafe can stop us from living our truth, learning new things about ourselves and having healthy relationships."

People who feel supported in their relationships and community tend to report better mental health and an increased sense of freedom, Hargons added. In contrast, those with less support are more likely to be depressed, anxious and lonely.

The importance of a sense of safety, and the consequences of not having it, are particularly pronounced among members of the LGBTQIA+ community, who are more vulnerable to discrimination, oppression and violence.

Research indicates LGBTQIA+ individuals are more likely to experience mental health problems, such as depression, thoughts of suicide or substance use, compared to the general population due to the lasting mental health effects of stigma, prejudice and discrimination.

"As a person that's part of the LGBTQIA+ community, each time you meet someone else, each time you think you're getting into a relationship or want to connect that person with family or friends, you're taking a risk that you're coming out again and again. Coming out is not a one-time thing. It's an ongoing process," Harris-Jackson said, adding that people who live in rural or historically conservative areas may feel particularly isolated and apprehensive about disclosing their identity.

"There's a very broad spectrum to that safety that's not just about safety within the sexual relationship, but contextually, societally safe as well," she added.

Although having a supportive, caring community can promote a sense of security, Hargons emphasized true sexual liberation requires dismantling and rebuilding systems that perpetuate oppression. That includes the nation's sex education system, through which comprehensive, medically accurate, sex-positive and queer-affirming information is inaccessible to most students.

Currently, just 10 states require instruction to affirm LGBTQIA+ health or identity, and according to Sex Ed for Societal Change (SIECUS), only five states mandate comprehensive, inclusive sex ed that affirms all sexual orientations and gender identities and expressions. At the same time, six states require a curriculum that is unfavorable toward LGBTQIA+ individuals.

Flowers and Jackson-Harris agreed that, regardless of sex, gender or sexual orientation, there's power in owning your sexuality, knowing what makes you feel attractive, desirable and confident, and feeling able to express your wants and needs without fear of ridicule or rejection.

"When we know and identify our needs and communicate them to others, we're more likely to get those needs met," she explained. "It's almost like writing out a list of what you'd like for your birthday and sharing it with your loved ones. If you know what will make you happy, you tell others. And when they meet those needs, everyone wins."

Numerous studies have demonstrated mental and physical health are directly connected, and mental illnesses can manifest in physical and psychiatric symptoms. Mental illness can also impede a person's ability to care for themselves or others. Occasionally, it spurs decisions that cause catastrophic harm.

"It is a critically important component of public health. We have to think about caring for an individual's mental health the same way we would think about caring for someone's physical health," Harris-Jackson said. "If we know that someone is out here with a virus, for instance, we want to make sure that we encourage that person to get treatment and to quarantine, to give themselves time away from others until they are feeling better and until they can no longer pass on that virus to other people."

These preventative and protective measures, Harris-Jackson continued, which are standard protocol during flu season, for example, can be lifesaving. She explained that such steps are equally vital in mental health. Without them, individuals, families and entire communities can face devastating ramifications, particularly when someone takes their own life or that of another person.

"All health is connected," Hargons asserted, noting how the COVID-19 pandemic underscored the interlinking between mental and public health.

As well as the pandemic's physical implications, the profound, widespread isolation, fear, anxiety and grief contributed to a surge in psychiatric diagnoses, she added. Based on surveys before and after the pandemic, the number of U.S. adults with stress, anxiety, depression and substance use disorders increased dramatically, according to information from Mayo Clinic.

Promoting mental health—and healthier mentalities around sex and sexuality—can have various positive impacts on individuals and the public. People who experience shame and guilt around sex and sexuality may feel less comfortable in their bodies and identities, Flowers explained. They may also be less likely to seek sexual and reproductive health care.

"Being more honest and less judgmental about sex and sexuality is one of the best ways we can help keep ourselves and the people we know healthy," she said.

People with various types of mental health issues frequently experience sexual side effects, which can present in myriad ways, ranging from low libido and painful sex to sexual compulsivity.

Although most mental health conditions can impact sex, anxiety, depressive and bipolar disorders, ADHD, and schizophrenia are among the most prominent, according to Harris-Jackson and Hargons.

Prescribed medication—a lifeline for many people with mental health conditions—is widely known to produce sexual side effects, such as erectile dysfunction (ED) and low libido.

"Anxiety disorders can precipitate sexual pain and avoidance due to fear of sex and difficulty with arousal. Depressive disorders can impact motivation to pursue sex through anhedonia [a reduced ability to experience pleasure] and fatigue. PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder] can also impact people who've experienced sexual trauma," Hargons said.

"Bipolar disorders can lead to sexual compulsivity in times of hypomania or mania," she added. "Sexual and mental health overlap considerably, although many people don't know which comes first for them."

Hargons provided the example of depression and depressive episodes associated with bipolar disorder. During depressive periods, she explained, people may not feel as though they want to be in their body, let alone be touched by another person. Depression can also contribute to ED and painful penetration, as can anxiety, which frequently co-occurs.

"People have a hard time realizing that when we think about the sex or sexuality, we have to be able to be present in our bodies to have the full experience of pleasure," Harris-Jackson said. "And in order for us to be present in our bodies, that requires our minds to be present, to feel safe, to feel secure, to feel like we have a sense of desire or pleasure."

Removing barriers to care and improving the quality of mental health services could substantially impact the nation's physical and psychological well-being. As serious mental health challenges are significant causes of disability, unemployment and being unsheltered, investing in mental health could be economically advantageous.

Among the ways the federal government could address the nation's mental health crises, Harris-Jackson and Hargons cited the following:

- Better outreach and prevention measures for mental health issues

- Better reimbursement for medical doctors and nurse practitioners

- Enhanced community care services, including affordable support groups and counseling

- Expanded telehealth services for easier access to a mental health professional

- Financing for mental health facilities

"Many social determinants of health are naturally determinants of mental health. This includes affordable and adequate housing, food and nutrition security, violence reduction, and education programs that help increase mental health literacy," Hargons explained.

"For example, I direct the Neighborhood Healers Project, funded by SAMHSA, where we train Black community members in mental health first aid," she added. "This prevention and intervention approach ensures that our Neighborhood Healers Fellows can help other community members when they're experiencing stressors so that it doesn't progress to a diagnosis of mental disorders.

"But, if the person's symptoms are already in the clinical range, they have a list of mental health service providers to give them. The government should continue funding projects that address mental health from many directions."

On an individual level, Harris-Jackson encourages people to continue to tell their stories to diminish the stigma and shroud of silence surrounding mental illness.

"If you or someone you know is receiving mental health services, try to speak about that to remove the stigma," she said. "Tell your story, tell the story of others, speak about it, start to normalize it."