The Bewildering History of Valentine's Day

In the days leading up to February 14, grocery stores swarm with roving heart-shaped nylon balloons, mail carrier routes clog with orders of imported roses and lifesize teddy bears, and partners throughout the land scratch their head wondering what would be an astounding gift for their loved one.

And the internet floods with Valentine's Day origin stories. (But not as good as this one!)

Year after year, morning talk show hosts, news anchors, journalists and bloggers make a valiant attempt to unwrap the holiday's history, and year after year, we seem to come to the same conclusion—no one really knows how Valentine's Day began.

While some historians trace its roots to a bawdy and somewhat wild Roman festival, others cite Geoffrey Chaucer's "Parliament of Foules" as the inspiration. Even those who link the holiday to Valentine the saint disagree over which St. Valentine is the holiday's true namesake.

But with that series of disclaimers out of the way, here's one thing we do know about Valentine's Day: It's a holiday whose origins are as murky as they are decidedly unromantic.

Lupercalia: An ancient Roman fertility festival

When tracing the origins of Valentine's Day, some historians go as far back as ancient Rome. Every February 15 from as early the 6th century B.C.E., ancient Romans celebrated a fertility festival known as Lupercalia. Looking somewhat different from the rose-festooned and prix-fixe dinner-fueled celebrations of today, Lupercalia was a bloody ceremony characterized by animal sacrifice, whippings and wine-drenched debauchery.

As Noel Lenski, Ph.D., professor of classics and history at Yale University, describes the holiday, "[Lupercalia] was kind of a wild and raucous fraternity party," adding that, like a frat party, it was attended primarily by "a bunch of drunken guys."

But instead of business and accounting majors, these drunken guys were priests from the order of Luperci. On Lupercalia, the reveling holy men would congregate in the Lupercal Cave, where city founders Romulus and Remus were legendarily nursed by a wolf. To honor the lascivious horned and hoofed god Pan, the priests sacrificed dogs and goats—instead of the more commonly sacrificed animals like pigs and calves—because they were thought to have more voracious sexual instincts.

Drunk, naked and smeared in dog and goat blood, the Luperci priests would run around Palatine Hill with strips of the hides of their freshly slain animal sacrifice. Any women they met along the way would get whipped with these bloody straps.

"This supposedly made the women fertile," Lenski explained. "In fact, women who wanted to become pregnant would purposely get in front of these people so they'd get beaten." He pointed to mosaics from that period depicting the festival, which show women being held up, stripped naked and happily accepting the whipping.

The rowdy fertility rite also may have been followed by a matchmaking lottery, some historians believe, when men would draw names of the city's eligible bachelorettes from a jar. The couple would be paired for the year and—if it worked out—eventually wedded.

St. Valentine of Africa

In the 5th century, Pope Gelasius I outlawed the observance of Lupercalia and replaced it with a day to honor the Christian martyr Saint Valentine.

"This is a thing that happens a lot in the Middle Ages," noted Elizabeth Nelson, Ph.D., a 19th-century pop culture expert and history professor at the University of Nevada Las Vegas. "The Church wants people to become Christians, so they lump together familiar pagan holidays with Christian ones." She cited Christmas, which draws many of its cultural aspects from pagan winter solstice celebrations.

But from the beginning, the true identity of the holiday's titular saint has remained somewhat mysterious. There are around a dozen saints named Valentine (or some variation thereof), at least three of whom were martyred on February 14 during the 3rd century A.D.

Little is known about the first St. Valentine, other than that he is believed to have died in Africa along with 24 soldiers.

St. Valentine of Rome

Of the three Valentini, the most popular might be St. Valentine of Rome. Legend has it that this St. Valentine was a holy priest who was executed by Emperor Claudius II on February 14, 270 A.D.

It's this version of the St. Valentine's Day legend that professional storyteller Hannah B. Harvey, Ph.D., often tells in lectures and highlights in her book, "The Hidden History of Holidays." According to the legend, Harvey said, "Claudius II canceled engagements and forbid marriages for conscripted soldiers so that they could focus on serving him rather than missing their sweethearts and family at home, since an untethered soldier could travel anywhere willingly."

Valentine—whether driven by a soft spot for romance or a priestly duty to prevent unwed soldiers from living in sin—defied Claudius the Cruel (as he was known to his subjects) and continued to conduct marriages for lovers in secret. When he was caught, the emperor ordered him to be beaten to death with clubs and beheaded.

St. Valentine of Interamna

Other historians point to Valentine of Interamna, the bishop of what is now modern-day Terni, about 65 miles northeast of Rome, Italy. Just like the other Valentine, this particular Valentine was also executed by Emperor Claudius II. Some historians believe that this St. Valentine sealed his fate by trying to convert the cruel one to Christianity. Because of similar timelines and origin stories, many historians suspect they may have been the same man.

One (or both, if indeed they are the same) of these St. Valentines is associated with another holiday origin story. The legend goes like this: While imprisoned and awaiting execution, Valentine found favor with the jailer's daughter. To thank her for her kindness, the prisoner wrote her a card and signed it "your Valentine."

Nelson, however, is skeptical of this story. "One: Paper is hard to come by," she said. "Two: Nobody is giving out pens to prisoners. And three: Most women aren't literate in that time, period."

"But it doesn't really matter," she added. "We like these origin stories because they give a sense of authenticity to the celebration."

Geoffrey Chaucer: 'Parliament of Foules'

The first official mention of Valentine's Day as a day for lovers is in Geoffrey Chaucer's 14th-century poem, "Parliament of Foules." This 699-line poem describes a group of birds who gather on "seynt valentynes day" to choose their mates.

Harvey, who favors this feathery romance over the dog-slaughtering, lady-whipping Lupercalia when explaining the origins of Valentine's Day to young audiences, noted that "the story is likely a veiled symbolic reference to Queen Anne of Bohemia, who at one time had three kings vying for her hand."

Victorian Valentines

Valentine's Day continued to pick up steam over the following centuries before taking off in the 1840s.

"That's when commercial manufacture of mass-produced paper printed matter—especially when combined with technologies that enabled color printing of pictorial elements—underwent a huge boom," said Annebella Pollen, Ph.D., reader in history of art and design at the University of Brighton.

At this time, increased paper production and printing presses made preprinted Valentine's Day cards affordable to the masses.

"Other practical reasons that helped the circulation and spread of printed Valentines included the expansion and improved efficiency of the postal service and the growth of literacy—more of the population could now read and write," she explained.

Also driving the rise of Valentine's Day was Victorian-era Romanticism, a movement characterized, in part, by the exaltation of emotion over logic and of the senses over intellect and associated with the communication of sentimental feeling.

"Commercial Valentine card manufacturers capitalized on this expectation by developing a wide array of sentimental products for sale," noted Pollen.

Victorian-era card manufacturers' efforts worked, and millions of cards were produced and sent every year.

"At the most expensive end of the market, especially later in the 19th century, commercially produced Valentine's cards were beautifully elaborate and complex, with fine lace paper, foiled inserts, layers of fabric and cushioning, sometimes scented or trimmed with feathers and flowers," Pollen said. "And in addition to being really wide, Victorian-era Valentines were really comprehensive in their coverage of different moods—much more so than today, where they are almost universally sweet and loving."

19th- and 20th-century 'Vinegar' Valentines

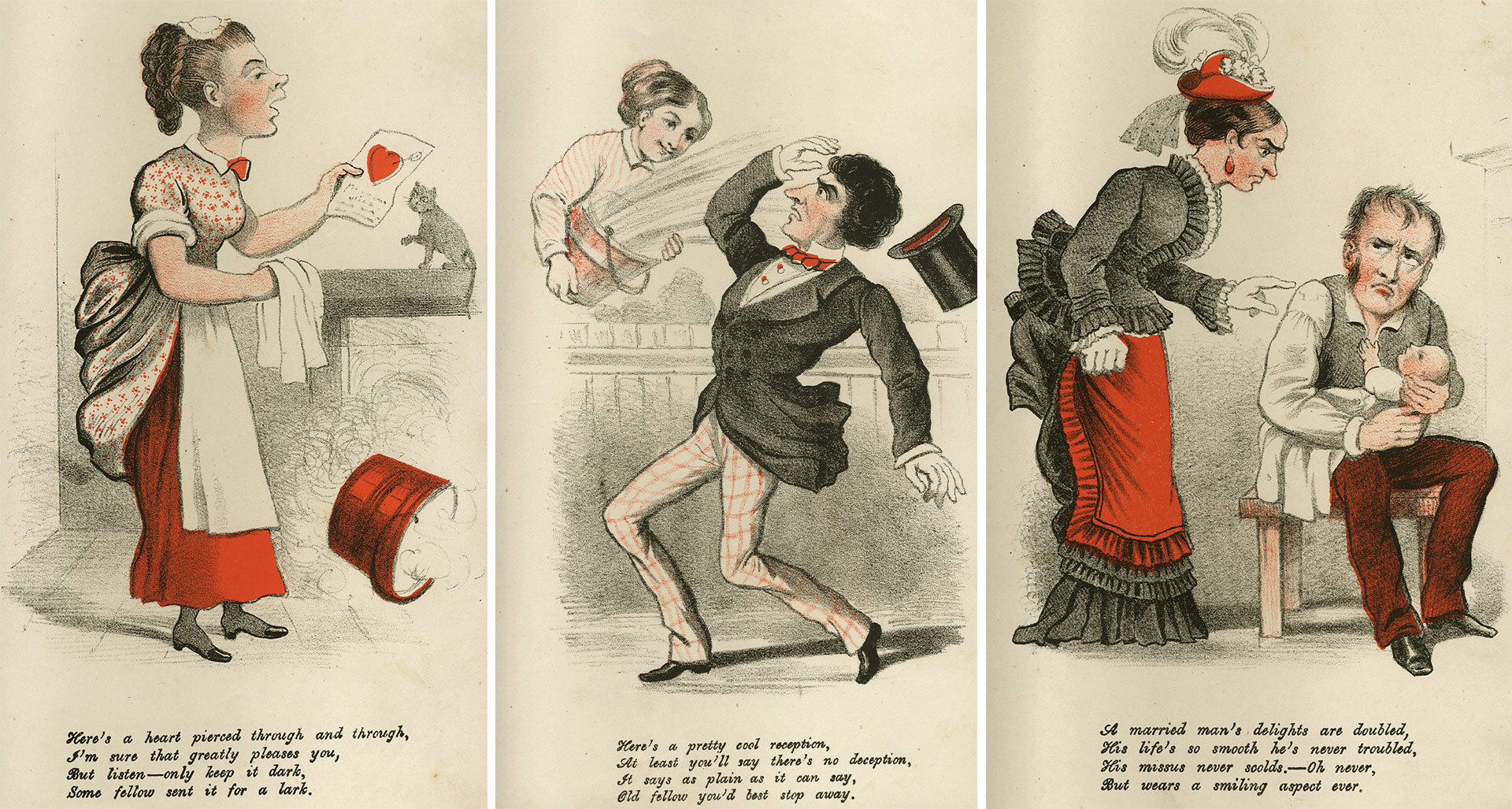

In fact, quite the opposite from sweet and loving, many Victorian Valentine cards were downright mean. As far back as the 1840s and up until the mid-20th century, it was not uncommon to send "mock" Valentines that hurled insults at the recipient.

Pollen, who first stumbled upon mock Valentines while researching a project on love and courtship, said that these "Vinegar" Valentines were enormously popular, representing between a third to a half of all Valentines sold in the Victorian period and circulated in the millions.

"Comic Valentines could be gently teasing or completely vicious," she said. "Some mocked the false and deceitful, who might be worthy recipients, but some made horrible comments about the recipient's physical appearance or financial status."

"There are also quite a few that mock excess drinking, which many in the 20th century would view as an addiction or a disease not suitable as a subject for a card," she added. "For example, another example from the Brighton Museum collection shows a drunken man wrapped around a lamppost, with the following verse:

"The kiss of the bottle is your heart's delight, And fuddled you reel home to bed every night, What care you for damsels, no matter how fair? Apart from your liquor, you've no love to spare."

If these Valentine's Day cards sound nasty to you, you're not alone. Pollen said that even in less-politically-correct Victorian times, many of the cards were not warmly received.

"Where I have been able to find traces of their effects, there are many examples of upset people," she noted. "News reports reveal cases of violence, with fists and guns, following fights after horrible Valentines were sent. There were even reports of suicides."

Valentine's Day in 2022

The commercialization of Valentine's Day—along with many other holidays— would continue into the coming years, noted Elizabeth Nelson. In the 20th century and into the 21st century, the industry expanded from simple paper cards to include everything from flowers and stuffed animals to gummy penises and edible massage oil.

Hallmark, founded in 1911, played a key role in engaging elementary school students, shifting the focus from receiving a single sincere Valentine to the competitive collecting of cheap, multiple cards, Nelson noted.

But while the holiday gets its fair share of overcommercialization criticism, Harvey believes the holiday is important because it's one of the ways we formally recognize in our culture that love exists and that we celebrate it.

"When I'm telling a kid-friendly version of Valentine's Day history, it's always the mention of 'love' that evokes 'aaaw' and 'eeew!' from elementary school kids—they're learning how to deal with (and name, and recognize) their feelings and emotions," she said, "It's a big deal growing up, to have adults sanction a public experience where you express love. That we tell our kids, it's okay to have these feelings and it's actually really sweet and part of what makes the world work."