Vaginal Fistulas: The Abnormal Connection

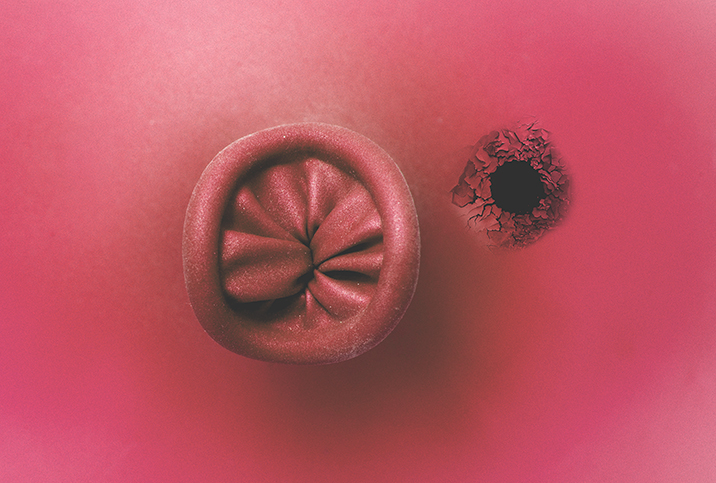

A fistula is one of the more common and uncomfortable conditions the human body may experience. It is an abnormal connection between two organs that may occur anywhere within the body, usually following an injury or prolonged strain.

Vaginal fistulas are the most common type experienced by women, though other reproductive organs, such as the uterus and cervix, may also be affected. A vaginal fistula is an abnormal opening between the vagina and another organ (bladder, colon, rectum, etc.).

"Essentially, there is a weakening in the tissue or a poorly healed opening postsurgery that allows two cavities to communicate that normally wouldn't," said Kiarra King, M.D., F.A.C.O.G., an OB-GYN in Chicago.

Vaginal fistulas are differentiated into subtypes:

- Rectovaginal fistula: where an opening links together the vagina and rectum

- Vesicovaginal fistula: an abnormal connection between the vagina and the urinary bladder

- Enterovaginal fistula: one that develops between the small intestine and the vagina

- Ureterovaginal fistula: an opening that develops between the ureter and the vagina

- Urethrovaginal fistula: one that develops between the urethra and the vagina

What causes vaginal fistulas?

Several things can lead to vaginal fistulas. For the most part, fistulas of the vaginal region are caused by prolonged strain during childbirth, which causes some blood vessels to be cut off. This lack of blood flowing into the area leads to tissue death—essentially, the degeneration and dissolving of tissues between organs—thus forming the fistula.

The condition isn't limited to childbirth, however. "Vaginal fistulas can result from an injury that can occur rarely during labor, delivery or surgery. They can also occur after radiation treatment, from inflammation, or an infection," said Amy Roskin, M.D., chief executive officer of The Pill Club.

In highly developed countries, vesicovaginal fistulas occur if the urinary bladder is damaged during pelvic surgery, such as a hysterectomy. However, in developing countries where childbirth occurs without professional medical intervention, prolonged labor lasting three to five days is the primary factor.

The pressure of the unborn child within the mother's birth canal cuts off blood flow to the tissues between the vagina and either the rectum or the bladder. The subsequent birth then leads to what is known as a severe vaginal tear.

Other potential causes for vaginal fistulas include the following:

- Pelvic fractures

- Vaginal or cervical cancers, as well as necessary radiation therapy

- Glandular abscesses near or around the rectum

- Inflammatory bowel diseases, such as ulcerative colitis, megacolon and Crohn's disease

- Infected episiotomy post-childbirth

In particularly extreme cases, repeated sexual abuse and violent rape may also cause vaginal fistulas in the victim.

Symptoms of a vaginal fistula

Typically, vaginal fistulas don't really hurt, but they can be uncomfortable and more than a little embarrassing.

"A woman with a vaginal fistula may experience persistent discharge from the vagina. Depending on the type, women can leak urine or stool into the vagina," King said. "Because of this, they may notice a foul odor related to the discharge. Additionally, due to the persistent presence of urine or feces, vulvar (external genitalia) irritation and infection can occur."

Most women who develop vaginal fistulas may experience the following symptoms:

- Fever, consistent with a rupture and a potential infection

- Lower abdominal pain, similar to cramping

- Lower back pain (particularly in the case of a rectovaginal fistula)

- Diarrhea

- Weight loss despite no change in dietary habits or exercise routine

- Nausea with or without vomiting

In the case of rectovaginal fistulas, additional symptoms include the following:

- Passage of stool, gas or pus from the vagina

- Malodorous and/or unusually colored vaginal discharge

- Recurring vaginal or urinary tract infections

- Moderate to severe irritation of the vulva, vagina and perineum (the physical border between the vagina and anus)

- Pain during intercourse

- Constant vaginal pain

For vesicovaginal fistulas, incontinence—the inability to hold in your urine or to control the impulse to urinate—is a telling sign. In the case of smaller vesicovaginal fistulas, their presence may manifest through thin, watery vaginal discharge.

Diagnosing and treating a vaginal fistula

Usually, a pelvic exam will suffice if a physician suspects a patient may have a vaginal fistula. This exam is performed along with a look at the patient's medical history. The doctor will check for potential risk factors, including recent pelvic, urogenital or lower GI tract surgery, recent childbirth (especially if the patient underwent prolonged labor), infections and whether or not the patient experienced any form of radiation therapy.

If this type of diagnostic is inconclusive, the doctor may mandate any of the following laboratory tests or procedures:

- Bladder-specific dye test

- Cystoscopy to determine whether the bladder or urethra are damaged

- X-rays, either a retrograde pyelogram or a fistulagram

- Flexible sigmoidoscopy in the case of rectovaginal fistulas

- CT urogram scan

- Pelvic MRI

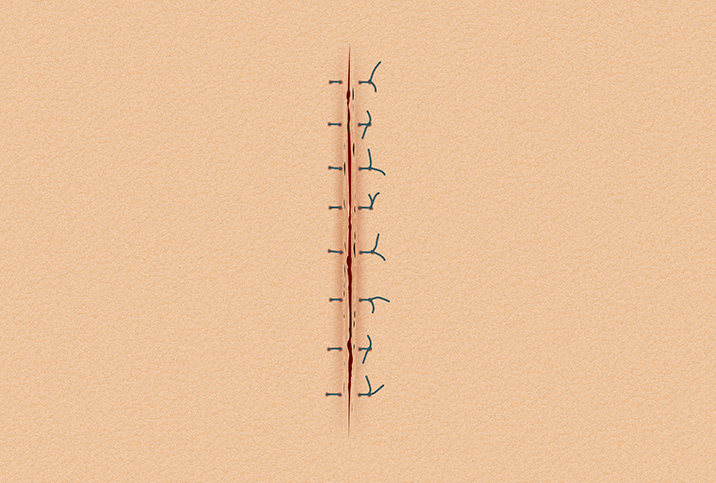

Once you are diagnosed with a fistula, a fistula repair is in order.

According to Kelly Culwell, M.D., an OB-GYN, fistulas usually require surgery to close the opening. A fistula repair is a surgical procedure that closes the defect that has allowed the spaces (such as bladder and vagina) to communicate.

"Occasionally, some small fistulas can heal on their own if caught early by draining the bladder continuously with a catheter so no urine can leak through the opening while it heals," Culwell said, "or for fistulas between the rectum and bladder, by treating diarrhea while also avoiding constipation or the need to strain with bowel movements."

In cases where the patient needs surgery to relieve the pain and discomfort of a vaginal fistula, the type of surgery to be performed depends on the type of fistula involved and its location.

Sometimes, standard abdominal surgery involving scalpels and putting the patient under a general anesthetic will suffice. Particularly deep cases are treated via laparoscopic surgery, wherein the attending physician makes a series of small incisions to insert micro-cameras and surgical tools.

In some cases, surgical adhesive, a binding compound made of natural proteins, may be used to seal up the fistula. Adhesive or glue treatment is often accompanied by an antibiotic regimen to treat any infections caused by the fistula.

If you've been diagnosed with a vaginal fistula or think you may have one, don't despair. Help is available. Talking about vaginal issues can feel awkward, but it's crucial to communicate with a medical professional with whom you feel at ease sharing your symptoms. Openness and honesty with your healthcare provider or team is essential for your full recovery and healing.