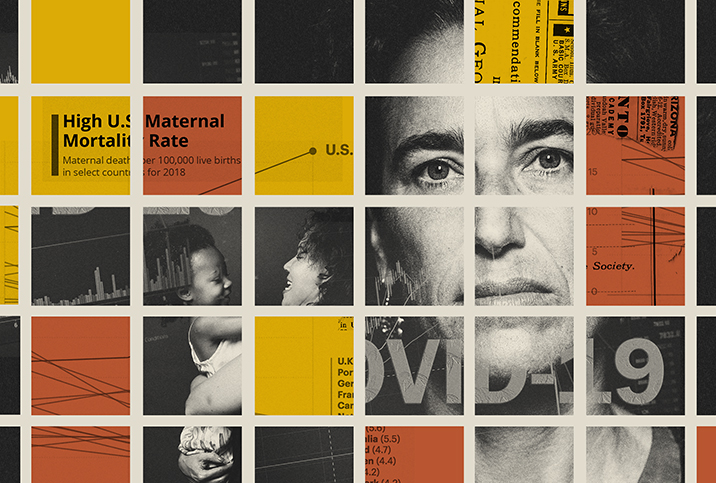

Black Women Are Much More Likely to Die From Childbirth

The United States has the highest maternal mortality rate (MMR) in the developed world, and we are the only developed country where that rate is increasing.

When the numbers are broken down by race, it tells an even more complex story: Black mothers in the U.S. are dying at a much higher rate than white or Hispanic women. In 2019, the maternal mortality rate was significantly higher than in 2018, according to a report released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in April 2021.

In 2019, the maternal mortality rate (number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births) was:

- U.S. (overall): 20.1

- Hispanic: 12.6

- Non-Hispanic white: 17.9

- Non-Hispanic Black: 44.0

This isn't new information. Depending on the year, Black mothers are two-and-a-half to four times more likely to die from complications related to pregnancy. In certain states, the statistics are much worse. In 2018, Black women in New Jersey had a maternal death rate of 102.3 (deaths per 100,000 live births)—seven times the maternal death rate of white women.

There are many complicating factors around statistics like these, but socioeconomic status, education and preexisting conditions cannot fully explain the difference. Studies have shown college-educated Black women are more likely to have a pregnancy-related death than white women who don't have a high school degree.

Even fame doesn't protect Black women. Serena Williams has talked about her near-death experience following the birth of her daughter, in which she had to demand proper medical care. Beyoncé experienced preeclampsia, a life-threatening pregnancy complication that required an emergency C-section of her twins.

Erica Garner, who became a social justice activist after her father, Eric Garner, was killed by a police officer in 2014, died of a heart attack at age 27. Her death came three months after her first heart attack, which occurred shortly following the birth of her son. It was discovered she had an enlarged heart.

In addition to MMR, another metric used to capture the death rate for women is pregnancy-related mortality (PRM), which tracks mothers through the first year after delivery. PRM has skyrocketed, from 7.2 in 1987 (the first year of data collection) to 17.3 in 2017. Again, Black women score poorly, dying at three times the rate of white mothers.

One-third of maternal deaths occur between one week and one year postpartum, and cardiomyopathy, a weakened or enlarged heart—like Erica Garner had—is the leading cause of these deaths. Who is most likely to die from postpartum cardiomyopathy? Black women.

For every metric, Black women have worse pregnancy outcomes compared to women of other races. Black fetal mortality rates (miscarriage and pregnancy loss) and Black infant mortality rates are also higher than for their white and Hispanic counterparts.

Reports indicate that an increase in Black birth attendants, such as doulas and midwives, for Black mothers leads to better birth outcomes.

Tara Mylers is a Black mother living in Philadelphia. When she was 36 weeks pregnant with her second child, she experienced a sharp, continuous pain in her abdomen and went to the hospital. They sent her home because she wasn't having contractions. This back-and-forth continued for three days.

The doctors kept insisting it was a normal pain from her cervix stretching. "But I knew it wasn't stretching. I knew it wasn't normal. You're not supposed to be in that kind of pain with just stretching. This wasn't my first baby," Mylers said. "They just brushed me off, they didn't take me seriously—a single, Black woman."

The advice Mylers received was to "just go home and put your feet up." The medical personnel never did an ultrasound to check on the baby. If they had, they would have discovered Mylers' placenta was separating from the uterine wall.

"I was really trying to demand for myself. But the doctors were like, 'Look, you're not contracting. Go home.' So I had no choice but to leave," she said. "And imagine leaving in the same pain, going through a whole 'nother night in that same pain. Beginning of the next day, I can't take it, so I'm going back. Something must be wrong. This pain is not normal."

On the fourth day, Mylers called 911 and went to a different hospital by ambulance. She was fully dilated when she arrived, but her baby's umbilical cord was coming first and she needed an emergency C-section. She never got to see her baby alive. By the time she woke up from general anesthesia, her baby, Michael Troy King, had passed in his grandmother's arms. The hospital provided no medical care for Michael. He had lived for only 22 minutes.

Thinking about it later, Mylers said, "Sometimes we're not taken as seriously when it comes to medical situations. And that case is a perfect example. Why, if I'm coming in that many times and I'm in pain like that, why wouldn't you check my cervix? And monitor me instead of keep sending me home? Same hospital, three days."

There was a lawsuit against the hospital, but they filed for bankruptcy before the suit was heard. "And to this day," Mylers said, "there's hurt and confusion. You know?" She pauses and gathers herself. "And it wasn't right. They didn't care."

What is the cause?

One single thing isn't responsible for the maternal mortality rates in the United States. The issue is complex and multifaceted. Often, many signs of an impending problem are overlooked until it is too late, even for white women. Half of these deaths are caused by a handful of conditions: hemorrhage, cardiovascular and coronary conditions, cardiomyopathy or infection. Shockingly, about 60 percent are preventable.

The CDC identified the strongest contributing factors of maternal death as:

- The patient's lack of education regarding warning signs.

- Inadequate provider care.

- Problems in the "systems of care," which include access to health care and communication between providers.

The CDC acknowledged these factors are intermingled and there is a component of social inequality that needs to be addressed in order to effect the necessary changes.

Therein lies the problem: There are two separate battles. The U.S. maternal mortality rate needs to decrease, but in order to achieve this, birthing outcomes of the Black community need to be improved. Accomplishing this second goal requires that systemic racism in the United States be recognized and addressed.

Studies indicate the reason Black women and their babies are more likely to have worse birth outcomes than white women and their infants could be from the cumulative effect of racial bias itself. These factors include increased levels of poverty, decreased access to medical care and healthy foods, epigenetic changes caused by high levels of stress and medical professionals not believing Black people when they report pain. An enlarged heart, such as Erica Garner had, can be caused by physiological stress, including high blood pressure.

What can be done?

California started an initiative in 2006 to create a protocol for two of the most common causes of maternal mortality: hemorrhage and preeclampsia. By 2013, California's MMR had decreased to 7.3, half what it had been in 2006 and one-third the national rate. This success was attributed to having a specific plan in place to handle the more common kinds of birth complications. Similarly, when Britain focused on reducing deaths from preeclampsia over a three-year period, there were only two deaths attributed to this condition.

Additionally, reports indicate that an increase in Black birth attendants, such as doulas and midwives, for Black mothers leads to better birth outcomes.

Kira Kimble is a doula and doula trainer in Charlotte, North Carolina. She founded Charlotte's first black-owned doula agency, MINE-R-T Doula Company. "We are all doulas of color who are able to provide a deep level of cultural competency and awareness," Kimble said. "We are able to connect with our clients on a level that helps them emerge from childbirth whole and with less trauma."

Kimble explained how doulas address the three areas the CDC identified as factors in maternal mortality:

- Doulas offer childbirth education for couples to prepare them for the birth and explain possible intervention methods.

- Doulas provide continuous care for the mother, beginning even before conception if needed, and continuing into the postpartum period. "Our traditional postpartum care draws from the wisdom of indigenous practices to promote mental, emotional and physical healing following birth," Kimble stated.

- Doulas are advocates for their clients in the healthcare system. Kimble's doulas attend births in hospitals, birthing centers and homes, and can go with the mother if she needs to transfer to a different facility.

Kimble travels throughout the Carolinas, Georgia and Florida to train doulas. "I am developing doulas who are capable of providing effective support to individuals and couples throughout their pregnancies," she explained. "My doula training covers the history of birth work, how systemic racism contributes to disparities in birth outcomes and what doulas can do about it. My doula training workshops do not shy away from difficult subjects. Participants are challenged and encouraged to explore their own biases and beliefs."