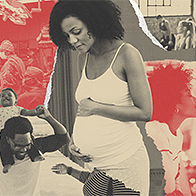

Black Women Are Less Likely to Receive Care for Postpartum Depression

Postpartum depression (PPD) is a public health issue affecting about 1 in 8 women who have recently given birth, according to research conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). COVID-19 likely exacerbated instances of postpartum depression by decreasing access to social and professional support and heightening infant and parental health concerns.

Black women have a significantly higher risk of developing postpartum depression than white women. But they are less likely to receive care for it.

Low-income white women are twice as likely to initiate mental health treatment after delivery compared to low-income Black women, according to a 2011 study in the journal Psychiatric Services. Black and Latina women who initiated care are less likely to receive follow-up treatment or continued treatment.

Postpartum depression is debilitating and can be characterized by mood swings, irritability, sadness, an inability to connect with the infant, trouble sleeping, suicidal ideation and difficulty concentrating, among others. The condition impacts not just the birthing parent but also the baby, family and community.

Therapy, medication and support groups can be effective treatments for postpartum depression, assuming an individual is able to receive these treatments in the first place, which entails receiving a proper diagnosis.

Reasons behind the disparity in care

Lack of support is a chief reason behind the inequity in care for Black mothers, said Shyana Broughton, executive director of Our Mommie Village, a full-service postpartum support community in Buffalo, New York.

"Mothers are leaving the hospital after a few days without a plan of support for themselves when they are home," Broughton said.

The reasons are also systemic. Implicit bias directly impacts the quality of care someone receives, which could include timely diagnosis and prescriptions.

"The most common cause is based on biases that exist in our current delivery of care system," said Kay Matthews, L.C.H.W., founder and executive director of the Shades of Blue Project, an organization in Houston dedicated to breaking the barriers in maternal mental health.

A damaging and wrongful school of thought is the assumption that Black women are stronger than others and don't need any help, which couldn't be further from the truth, Matthews said.

"It is imperative to stop this thinking as it is very harmful to the mental health and well-being of Black birthing individuals," Matthews said.

"Black mothers, especially, feel that it is a badge of honor to do things alone," Broughton added.

Matthews noted the "superwoman syndrome" and the immense pressure some women feel to always be strong and never accept permission to breathe and seek treatment.

The "superwoman syndrome" assumption is also pervasive in health care. Some providers erroneously believe Black patients have stronger bones and thicker skin, according to a 2016 study on racial bias published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Stigma about seeking mental health support also exists in the Black population.

"In my experience as a Black mother—children ages almost 17, 11 and 9—in the Black community, it is still taboo that this is even an issue," Broughton said. "If you appear not to be able to handle this transition to motherhood without complaining, then you may be considered weak, which is so backward to me."

The fear of being penalized or risking a visit from child protective services is a very real concern that prevents some Black mothers from seeking support.

"So often, Black birthing individuals are penalized within systems of care for saying that they are mentally struggling or feel like something is wrong," Matthews explained.

"Instead of being extended a helping hand, so often, police are involved and often include children's protective services. To all avail, too many unnecessary steps have been enacted that lead most to deal with their struggles behind closed doors," Matthews said.

Research substantiates the concern for police or child welfare agency involvement. Caseworkers deem Black mothers more unfit to parent at a higher rate than white people. Black children are also more likely than white children to be removed from their homes.

Postpartum depression screening tools

Postpartum screening tools used by clinicians were developed through research on white women, Virginia-based psychologist Alfiee Breland-Noble, Ph.D., M.H.Sc., told NPR in a 2019 report.

A 2010 study in the journal Pediatrics examined the accuracy of screening tools for postpartum depression and suggested that urban, low-income Black mothers may benefit from a lower threshold for the score at which they identify depression, similar to grading the test on a curve. This was the case for some, but not all, of the routinely used screening tools. The reasons for this are unclear. It is also unclear if these differences would persist over different socioeconomic situations or how generalizable these findings may be.

Different cultures may also speak about mental health in varying ways, so indicators of postpartum depression for white people may be less relevant for Black people. Variations in identifying symptoms of postpartum depression may cause clinicians to miss the diagnosis altogether. For example, Black patients are less likely to use the word "depression," according to a 2011 study in the International Journal of Culture and Mental Health.

Mental health resources are available

"It is hard for individuals to focus on their mental health when they are also struggling to obtain basic needs, such as diapers, clothing and financial support. Meeting those needs first is how you start to combat the mental health struggles that may exist," Matthews said.

Sometimes, support is as easy as calling on someone to assist with the bedtime routine while mom gets to rest, Broughton added.

"When it is more complex, each mother has access to a mental health counselor that is available any time they feel they need extra support," Broughton said.

Creating a community where new mothers can potentially bond over shared experiences and feel less alone can be helpful.

"There are resources for Black women with PPD, but they are predominantly white spaces," Broughton said, adding that the majority of clients her organization serves in western New York are Black.

Catching the warning signs for postpartum depression is imperative.

"At Our Mommie Village, we believe that addressing the needs of these Black mothers before they are completely overwhelmed is the key," Broughton said.

Ensuring that Black mothers see they are not alone and can find solutions is part of absolving the inequity in support, Matthews explained. Adequate resources with culturally competent providers are part of the solution.

"There is a collective effort that must take place for this to happen," Matthews said.