The Husband Stitch Represents Systemic Issues in Health Care

Stop me if you've heard this one before: A woman has just given birth, and a doctor is in the process of repairing a tear in her perineum (the skin between the vagina and the anus) by applying stitches. Her husband catches the eye of the doctor and says, "Hey, Doc, throw in an extra stitch for me." (In some versions of the joke, the doctor responds by saying, "Sure, how small do you need it?")

The implication is that the vagina was stretched during birth and now needs to be tightened—not for the benefit of the birthing person, but for the sexual pleasure of a male partner. The added stitch isn't just about "correcting" a vagina to its pre-birth state, said medical historian Sarah Rodriguez. "It's also, wink-wink, 'improving.'"

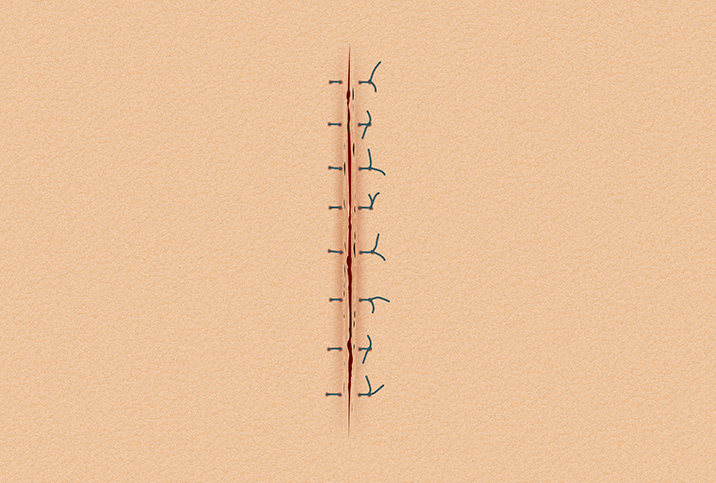

The extra, unnecessary stitch is often known as the "husband stitch," and it is not an official medical procedure. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends repairing tears that are bleeding and that have distorted anatomy. But the repair should be to restore normal anatomy, and if the tear is superficial with no bleeding, stitches may not be needed at all.

"In my career, which is 30 years, the only person I've heard talk about the husband stitch is the husband. And it's usually inappropriate humor," said Geoffrey Cundiff, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of British Columbia.

But the myth of the husband stitch looms large, and women have talked about receiving a husband stitch, with horrific results. Sometimes, women only find out it's happened after months or years of painful intercourse.

The extra, unnecessary stitch is often known as the 'husband stitch,' and it is not an official medical procedure.

Rodriguez said the narrative of the husband stitch likely came from activists in the '70s who were critiquing routine episiotomy and episiotomy repair. In the early 20th century, women started going to the hospital more to give birth, instead of in the home. Doctors started seeing more tears during labor—possibly because birthing positions changed in the hospital to lying down.

In this context, doctors increasingly performed episiotomies, which is a cut to the perineum during labor to enlarge the vaginal opening. Doctors thought if they controlled the cut, women would tear less, preventing dangerous third- and fourth-degree tears.

But this wasn't necessarily the case. Not only did routine episiotomies not prevent tears, but they can also lead to an increase in tearing. "When I explain this to my students, I actually use a piece of paper, and I make a cut with scissors, and it tears easier when you've made a cut with scissors than if you just try to tear paper without the scissor cut," Rodriguez said. In addition, ACOG says women who underwent routine episiotomies were more likely to have pain with intercourse in the months following labor.

Episiotomies became routine practice by the '50s and '60s, and the person in labor very likely didn't specifically consent to the procedure—it was just seen as a part of giving birth in a hospital setting. When activists talked about the husband stitch, they were critiquing the idea that episiotomy should be routine for every person giving birth. By labeling episiotomy repair as something that was done for men and not the patient in labor, activists were able to draw attention to the practice and reconsider who it was benefitting.

Episiotomies are no longer recommended to be routine, but they may be used in certain scenarios, like when forceps are used in birth. ACOG states that clinician judgment is the best guide for deciding when to use an episiotomy.

And, importantly, the conversation around consent in medical settings has evolved. Patients have the right to informed consent, which means they have a right to information about possible outcomes of procedures—and a right to decline medical interventions and treatments.

Informed consent is a right even in an emergency situation, like when labor has a complication. But birthing people often face sex-based discrimination that may violate that right.

Farah Diaz-Tello, senior counsel and legal director for reproductive justice organization If/When/How, wrote a paper in 2016 that looked at instances of coercion of pregnant people while receiving maternity care. In the paper, she cites a 2014 Maternity Support Survey from the U.S. and Canada that found more than half of birth workers witnessed a physician perform a procedure against a woman's will, and that almost two-thirds had often or occasionally seen providers perform a procedure without giving a patient a choice, or time to consider the options.

"It's marginalizing, it's infantilizing, and it also undermines the pregnant person's own agency and their ability to take on risk for themselves," Diaz-Tello said.

Even if a medical provider has the best of intentions and has participated in informed consent, stitching a person too tight can happen by accident. "Women who are pregnant have a lot of blood supply and they bleed a lot, and with really bad tears you have to sew fast and stop the bleeding. In that context, sometimes people don't get things quite right," Cundiff said.

In the past, when a person had pelvic organ prolapse, which occurs when pelvic floor organs like the uterus or bladder shifted and may be bulging into the vagina, the goal was to close the vagina to keep things from coming out, Cundiff said. This surgery isn't an anatomical repair; it actually changes anatomy by pulling muscles in tighter. "That has remained a technique that some people use. I think it's people who don't have complete training perhaps as a reconstructive surgeon," Cundiff said.

The story of the husband stitch is powerful because it encapsulates a lot of systemic problems in medical care: incompetence, sex-based discrimination, violation of consent and prioritizing men's sexual desires over women's well-being. And historically, there is evidence of doctors mutilating women's bodies without their consent, so this fear isn't unfounded. Whether stitching too tight during repair of the perineum happens by accident or on purpose, the pain and fear patients feel are real.