We Need to Talk About Maternal Overdoses and Suicides

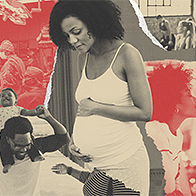

Over a Google Meet, Adrienne Griffen, M.P.P., executive director of the Maternal Mental Health Leadership Alliance in Arlington, Virginia, shows two photo collages. The first contains pictures that come up when you search for "having a baby" or "new parents." All of the images have warm lighting, and parents hold their newborns with pure adoration in their eyes.

The second collage shows photos of what you probably won't find when you Google "new baby": heaps of laundry, screaming infants and a toddler meltdown.

New parenthood is often glamorized, but for many people, it's a challenging transition that may come with high rates of depression, anxiety and other mental illnesses. Maternal mental health is not publicized as often as it should be, and the picture that's painted for new parents can be unrealistic.

While there is some awareness of postpartum depression, there is actually a wide variety of perinatal and postpartum disorders, including mood disorders, anxiety disorders, perinatal or postpartum psychosis, and perinatal or postpartum obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). And within each of these diagnoses lies a diversity of experiences.

The rates of suicidality among childbearing individuals climbed substantially from 2006 to 2017, according to a study published in JAMA Psychiatry. More than one-fifth of pregnancy-associated deaths from 2010 to 2019 were from suicide, drug use and homicide, according to a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

When pregnancy and caring for an infant is touted as blissful, perfect and always enjoyable, an individual's struggles are often compounded by an added layer of shame.

We don't often consider mental health a pregnancy complication, but it is, and unfortunately, it's all too common. For new parents, suicide and drug overdose are two of the leading causes of death. But despite these rising rates, both suicides and overdoses are omitted from published maternal mortality data.

The California Pregnancy-Associated Mortality Review examined suicides between 2002 and 2012. The review found nearly one-third of women used illicit drugs or prescription opioids during or after pregnancy, with substance abuse cited as a precipitating factor in almost 30 percent of the suicides. The report, which is the largest statewide in-depth review of pregnancy-associated suicide, indicated that most suicides in California occurred within six months to one year after childbirth.

Similarly, a 2017 study of perinatal suicide among Canadian women suggested that mothers were more likely to die by suicide nine to 12 months postpartum, which is past the time frame cutoff for classification as "maternal deaths" by the World Health Organization (WHO).

The WHO defines maternal death as "the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and the site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes."

Many pregnancy-related deaths occur after that 42-day period.

Who keeps track of maternal suicides and overdoses?

How we codify and count maternal suicides and overdoses is a confusing system, with a couple of different surveillance systems.

"Widely used maternal mortality surveillance statistics, most notably the maternal mortality ratio [MMR], exclude deaths from suicide and overdose," the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) told Giddy.

"Deaths from injury, such as suicide or overdose, among pregnant or recently pregnant persons are not assigned an ICD-10 code for obstetric deaths and are therefore excluded from the MMR," the department stated, referring to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, a system of diagnosis codes.

"Different surveillance methodologies than the MMR are used by states to monitor deaths from suicide or overdose among persons who died during pregnancy or up to one year after the end of pregnancy. Surveillance of non-obstetric deaths varies by each state's capacity for monitoring and reviewing these deaths," the department stated.

Griffen explained part of the confusion over the reporting: "We've got these two organizations within the CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] collecting data with two different endpoints, but neither includes accidental or incidental causes of death." These rates end up being omitted from published rates of maternal mortality, meaning the full picture is not being presented, Griffen explained.

"Each maternal death from suicide or overdose requires a complex, comprehensive case review to determine whether a given death was related to pregnancy and to identify those factors that might have been contributory," the CDPH said.

Maternal Mortality Review Committees, which are multidisciplinary teams that process maternal deaths in each state, do not require uniform data, according to a recent review by the Guttmacher Institute, a research and policy organization for sexual and reproductive health. Only 14 states, plus New York City and Puerto Rico, require an assessment of whether these pregnancy-related deaths were preventable.

"In California, maternal mortality surveillance and review teams examine trends and emergent issues and consult with subject matter experts to guide decisions regarding the focus areas of comprehensive case reviews. In-depth reviews are important because the data informs prevention or intervention strategies, but they are time-consuming and resource-intensive, so not all states—because of size or resource differences—can do the same approach," the CDPH stated.

Death certificates also under-categorize pregnancy-associated suicides. The pregnancy checkbox, which was added to death certificates in 2003 to help identify maternal deaths, is not utilized uniformly by all states.

"There needs to be just some standardization around the data; that would help immensely," Griffen said.

"Suicide and overdose deaths are included in pregnancy-associated deaths, which is a death in pregnancy and one year postpartum," said a spokesperson from 2020 Mom, a maternal mental health nonprofit organization based in Los Angeles. "Suicide and overdose death are counted as pregnancy-related deaths if they are deemed pregnancy-related by a maternal mortality review committee."

A pregnancy-related death is defined by the CDC as "the death of a woman during pregnancy or within one year of the end of pregnancy from a pregnancy complication, a chain of events initiated by pregnancy, or the aggravation of an unrelated condition by the physiologic effects of pregnancy."

Again, there isn't a standard approach by Maternal Mortality Review Committees, 2020 Mom pointed out.

Why have cases increased?

Mental health issues are often stigmatized in the United States. But when pregnancy and caring for an infant is touted as blissful, perfect and always enjoyable, an individual's struggles are often compounded by an added layer of shame. More awareness of perinatal mood disorders and recognizing the symptoms can help people access treatment sooner.

The ubiquitous increase of mental health issues caused by the COVID-19 pandemic certainly has not helped, although there hasn't been any tracking of suicide-specific maternal deaths in this time period, yet. Unfortunately, cases of maternal suicides and overdoses were increasing before the pandemic.

Addressing suicide risk in OB-GYN settings

When Griffen told her doctor she wasn't doing well, the OB responded with a quick "Would you like Prozac?" Griffen was handed a behavioral health card and sent on her way, and that was the extent of the conversation. There's often a disconnection between OB care and mental health, Griffen pointed out.

Griffen recommended cross-training OB-GYNs, who could then check in with patients about mental health each and every visit, alongside the typical prenatal and postpartum checks. An obstetric provider has ample opportunity to ask about mental health at each visit.

"An average person getting routine prenatal care and routine pediatric care will see a healthcare provider 25 times," Griffen said.

The California mortality review indicated that 51 percent of the women in the analysis had a good-to-strong chance of suicide preventability with missed opportunities to intervene.

Suicide and drug overdose are two of the leading causes of death for pregnant or postpartum individuals, Griffen stressed.

"You don't hear anybody really talking about [it, but] that is the gong I keep banging—that is unacceptable," Griffen said.