When Donating Your Embryos Is Not an Easy Decision

Kelly*, a mother of three in Chicago, was surprised one spring afternoon when she saw she'd missed a call from her 7-year-old daughter's dance teacher. Though they'd never called or texted before, the two women were acquainted and had had some lengthy conversations during pickup and dropoff. The teacher, who we'll call Nora*, was always complimentary of Kelly's three children, and had confided in Kelly that she was in her mid-40s and now wanting children. Kelly told Nora that she had gone through in vitro fertilization (IVF) and shared the name of her local doctor, in case Nora was interested in pursuing some iteration of IVF.

Assuming it must be about needing to cancel a class or an issue that had come up, Kelly called her back right away. But it wasn't a schedule change, or a discipline issue, or about dance at all.

Nora was calling to ask if Kelly and her husband Matt* would ever consider donating an embryo they weren't going to use to Nora and her partner. "She acknowledged that it was a huge ask and that I shouldn't feel pressure," Kelly said. "When you start having these conversations you very quickly get into all the technicalities because everyone wants to know the ins and outs of how the process works and so I guess I'd told her in one of our previous conversations that we had two frozen embryos remaining. She mentioned she would be happy to pay for them."

Kelly said she never would have accepted money for them, but she walked away from the initial conversation leaning toward the decision to donate.

"I want to help people that really want a child. I have these embryos that I know create what I believe to be really great little humans. And I don't think I have any intention of using them. There's no way you can prepare for a decision like this," she said.

The decision of whether or not to donate an embryo

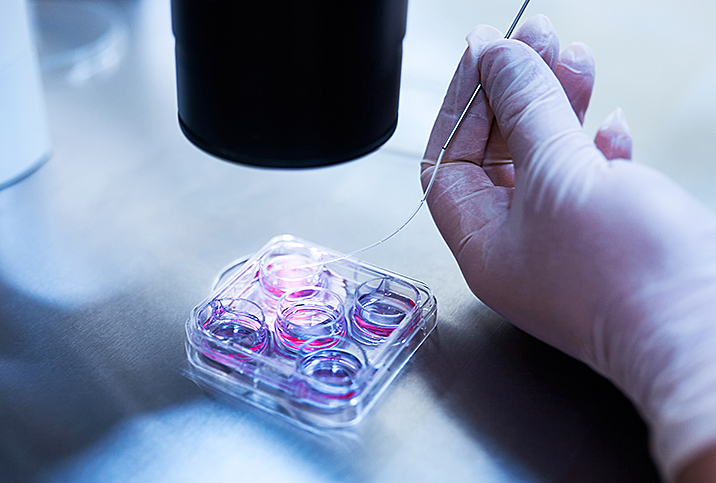

Unlike an egg, an embryo is made up of both parents' DNA. It's the step before the fetus and the only difference between the two is gestational age. "Embryos can be discarded, donated for research, or donated to another individual or couple," said Lucky Sekhon, M.D., a fertility specialist and board-certified OB-GYN in New York City.

According to 2021 reporting from The New York Times, there are as many as 620,000 frozen embryos in the United States currently. Of course, some of those will be used by the biological parents, but many will not. This puts so many individuals and couples in the position to make a difficult decision about what to do with their unused embryos.

Kelly and Matt spent four weeks going back and forth. "I felt so guilty. I want her to be happy and I want her to have the family that she wants. It felt like I was just being selfish," Kelly said. "You're not giving this child a chance at a life. From a decision standpoint, I felt like the only person I was protecting by not giving it to her was myself, my own emotions."

She said she found it impossible to predict how she would feel knowing there was a biological child of hers in the world, one whose life she wouldn't be much a part of but would probably see on Instagram and receive the occasional update on. It would likely have been easier, she thinks, to donate to either a family member or a close friend, or on the flipside, a total stranger. The liminal in-between space of an acquaintance was hard to imagine.

Other people deciding whether or not to donate may find themselves asking questions, such as: What if they knew that child ended up in the foster system? Or what if the adopted parents died? What would they say to their existing children about their biological sibling?

"I had to listen to my gut," Kelly said. "Maybe it would be great and everything would be fine, but who knows what kind of anxiety that decision could cause me. You can never take that decision back." Ultimately, she said, it boiled down to this question: Am I willing to open myself up to the possibility that I feel something that I don't want to feel for the rest of my life?

During the decision process, Kelly also realized that maybe she did want another child, which is ultimately what she told Nora, who cried when she heard the news, but was extremely understanding.

Kelly and Matt are not alone in their ultimate decision not to donate. "Most couples discard embryos or donate to research," said Lora Shahine, M.D., host of Baby or Bust on Apple Podcasts, and a double board-certified reproductive endocrinologist at Pacific Northwest Fertility and IVF Specialists. "In my experience when talking to patients about options, most feel uncomfortable donating to other people to try to conceive with. When people do decide to donate, they are typically excited to help other people with fertility challenges and report a positive experience."

And I want to stress that point here. Though I could not find a couple who donated to speak on record, for many people, donating to another couple is a joyful, fulfilling decision, though not one made lightly.

What to do with unused embryos

Ultimately, Kelly learned some medical information that made her and her husband decide that a fourth child would not be in the cards for them. And while they decided not to donate to another couple, they still have a tough decision to make when it comes to what to do with embryos.

Kelly explained that when the couple was in their late 20s and starting the IVF process, the clinic had them fill out a bunch of paperwork about the potential fate of the embryos. What would they do with them in the case of divorce? What if one parent died? This process, in a way, is similar to being asked to create a will before you've ever earned a dime. It feels hypothetical at best. How is anyone realistically supposed to know what they'll want to do with something they don't yet have?

Kelly said while she is finding the final decision to be extremely hard (she oscillates between calling her leftover embryos "blessings" and "unintended consequences"), she does not wish she thought more about the decision ahead of time. "I think when you're beginning the IVF process, sometimes, at least for me, ignorance is bliss. You don't want to be scared away from doing what you're doing, it's already totally scary."

One way to make it so fewer couples have to make these decisions is to limit the number of embryos produced to begin with, but this doesn't really make sense either. "It's not a good idea to purposely limit the number of embryos by starting out by inseminating a limited number of eggs," Sekhon said.

"Human reproduction is extremely inefficient—with a high rate of attrition from oocyte (egg) to embryo. Approximately 60 percent of fertilized eggs turn into embryos—but there could be a wide range and it is unpredictable," Sekhon continued. "If one purposely limits the number of eggs inseminated, it could increase the odds of not having embryos or having a sufficient number of embryos to facilitate family building goals."

Shahine agreed, but said she asks patients about any ethical considerations beforehand and if people express concern about too many embryos, "we talk about fertilizing only a portion of the eggs and freezing the rest as unfertilized eggs. Eggs are less ethically challenging to discard for many of my patients."

The fourth option

It seems there is general agreement that there are three things to do with unused embryos: discard, donate to science, donate to another couple. But, in reality, there is a fourth option, one many couples ultimately go with. They decide simply not to decide. They stop paying their storage fees without specifically telling the facility what they want done with the embryos.

Reporting from NBC News found that at least 90,000 frozen embryos are considered abandoned in the United States. When I told Kelly this stat, she made a sound of agreement then said, "Every year I get that invoice and it takes me longer and longer to pay it. And eventually maybe I'll just not pay it at all. I'll let it all float off into the distance, out of sight out of mind." She paused before adding, "That's awful."

*Names and identifying details have been changed.