Meet the First-Ever 'Vagina on a Chip'

A team of bioengineers at the Wyss Institute at Harvard University have designed a "vagina on a chip" to improve our understanding of the long-understudied organ.

The vagina chip, made from vaginal cells provided by two donors, is the most lifelike lab model of the vagina to date, successfully replicating the complex bacterial ecosystem known as the vaginal microbiome.

"While largely ignored in the past, the microbiome has been increasingly recognized to play a central role in health and disease in all organs, and this is definitely true in the female reproductive tract as well," said study author Donald E. Ingber, M.D., Ph.D., founding director of the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University.

Our understanding of the vaginal microbiome remains limited, in part, due to a history of research underrepresenting women's sexual health, but also because vaginal health and its relation to the microbiome is difficult to study in a laboratory setting.

According to Ingber, there are no suitable animal models, as animals have vastly different microbiomes than humans. In addition, there is great variation in microbiome composition among different patients, who may have different sexual histories and ethnicities, Ingber said.

Even in the same patient over time, there exist great variances in microbiome makeup during different stages of the menstrual cycle.

"While there are many different potential contributors to vaginal health that have been considered in the past—including differences in vaginal mucus, pH, lactate, microbiome, hormone levels, immune response, etcetera—it is impossible to control these parameters individually or collectively in human patients or even in an animal model," Ingber said.

Enter the vagina on a chip

Ingber believes the vagina chip to be a game changer in the field of vaginal health research. The living model of the human organ solves research hurdles by replicating physiological features of the vagina in a few key ways. For example, the chip changes gene expressions in response to the introduction of estrogen, indicating that it is sensitive to fluctuations in hormones—just like the real thing.

Ingber is hopeful that the invention can be used to test treatments for bacterial vaginosis (BV), an inflammatory condition that affects an estimated 21.1 million women ages 14 to 49 in the United States.

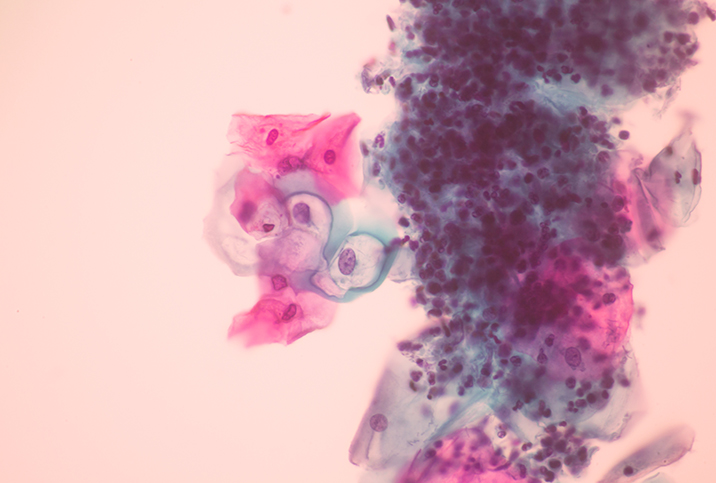

"Healthy vaginal health is associated with a community of bacteria in the vaginal microbiome that is dominated by a particular type of Lactobacillus species, Lactobacillus crispatus," Ingber explained. "[In BV], these bacteria decrease in numbers and are replaced by a diverse set of bacteria, often containing Gardnerella vaginalis.

"Importantly, BV is associated with adverse health outcomes, including increased susceptibility to and transmission of sexually transmitted infections, as well as increased risk of pelvic inflammatory diseases, maternal infections and preterm birth, which is the second major cause of neonatal death across the world," he said.

Traditionally, BV has been treated with antibiotics, but recurrence rates are very high.

How the chip can advance science

In one experiment, the scientists introduced Gardnerella vaginalis and other bacteria species associated with BV to the vagina chip. The "bad" bacteria caused the vagina chip's pH to increase, causing inflammation and cell damage, a reaction that mirrors what occurs in human vaginas with BV.

"It was very striking that the different microbial species produced such opposite effects on the human vaginal cells, and we were able to observe and measure those effects quite easily using our vagina chip," study co-author Abidemi Junaid, Ph.D., said in a statement. "The success of these studies demonstrate that this model can be used to test different combinations of microbes to help identify the best probiotic treatments for BV and other conditions."

In addition to testing new treatments for BV, Ingber hopes the vagina chip can be used to study infectious diseases caused by viruses and bacteria, as well as cancer progression. Ingber and his researchers have already designed a cervix chip that produces cervical mucus, and plan to study the two chips in conjunction to explore how cervical mucus influences health and pathogenic microbiomes.

"These chips could potentially be used to study female as well as male infertility, for example, sperm motility in the reproductive tract," Ingber said. "The vagina chip work was funded by the Gates Foundation, whose interest lies in developing health Lactobacillus crispatus consortia as live biotherapeutic products—essentially, probiotic therapeutic formulations—which they hope to advance to human clinical trials for reversal of BV in the future."