Cervical Cells Can Be Used to Predict Ovarian Cancer Risk, Study Finds

In 2022, the American Cancer Society estimates that 19,880 women in the United States will receive a new diagnosis of ovarian cancer. This disease causes more deaths than any other cancer of the female reproductive system, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

A polygenic risk score can help identify women at risk of developing ovarian cancer. This score measures your disease risk due to your genes. However, this type of risk score does not have a high level of accuracy and is not widely available.

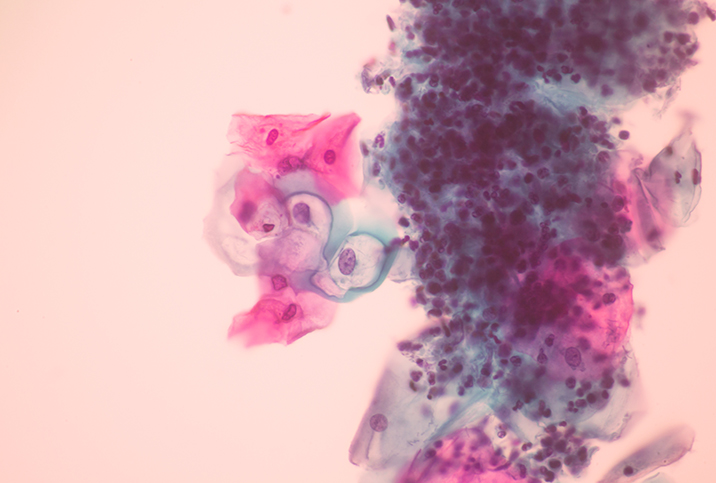

A 2022 study published in the journal Nature Communications indicated that cervical cell samples collected during a Pap smear may be able to predict ovarian cancer risk.

What did the study find?

"The study describes how a collection of cells from the uterine cervical area, much like what is done during a routine Pap smear, can be used to find or predict the risk of developing ovarian cancer," explained Steven Vasilev, M.D., a quadruple-board-certified integrative gynecologic oncologist, medical director of integrative gynecologic oncology at Providence Saint John's Health Center and professor at Saint John's Cancer Institute in Santa Monica, California.

The cells are collected using a brush from the cervical area but can originate from anywhere in the Müllerian (gynecological organ) tract or ducts, which includes the cervix, uterus, ovaries and fallopian tubes, Vasilev explained.

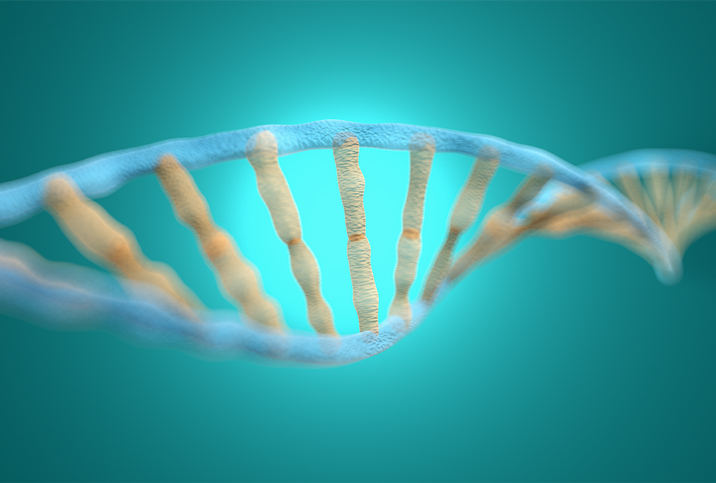

"Very sophisticated evaluation of these cells for epigenetic, meaning on top of the DNA, signatures or patterns involving degree and location of methylation was performed on patients known to have eventually developed ovarian cancer compared to those who did not," he said.

Methylation degree and location on the DNA is one of the ways your body turns genes on and off, including those which protect against or foster cancer development, Vasilev added.

"A specific methylation profile was identified that was strongly, but not perfectly, associated with the risk of ovarian cancer," he said.

The majority of ovarian cancers develop in cells that are part of the Müllerian ducts, which are an embryological structure.

The study was led by Martin Widschwendter, M.D., a professor of cancer prevention and screening and director of the European Translational Oncology Prevention and Screening (EUTOPS) Institute at the University of Innsbruck, Austria. He explained the study further: "The WID-OC methylation test used in the study allowed us to identify 71.4 percent of women under 50 years of age and 54.5 percent of women over 50 years of age with ovarian cancers with 75 percent specificity.

"Although we have not shown yet that the test is able to identify women at risk for ovarian cancer years in advance of their diagnosis, the fact that the test is not driven by the presence of tumor DNA in the sample suggests that the test would have identified women well in advance of their diagnosis," he explained.

Vasilev said this finding is noteworthy because it is yet another way to help identify women at the highest risk of developing ovarian cancer.

"Our results are significant because other methods developed to date, i.e., the polygenic risk score, to identify women at risk of developing this cancer lack the sensitivity and specificity to be used in clinical practice," Widschwendter stated.

How can cervical cells detect ovarian cancer risk?

"More and more data are accumulating that show cancer formation is a result of so-called field defects," Widschwendter said.

He explained this concept in detail: The majority of ovarian cancers develop in cells that are part of the Müllerian ducts, which are an embryological structure. As a fetus grows, the Müllerian ducts form the fallopian tubes, and the left and right ducts merge to form other parts of the female reproductive system, such as the uterus, cervix and the upper third of the vagina.

During the course of life from fetus through childhood, puberty and adulthood, factors such as hormone levels, diet and reproductive issues contribute to ovarian cancer formation in the fallopian tubes. These factors influence the fallopian tube cells' epigenome, or their "software." As these cells share their origins in the Müllerian ducts with other parts of the female reproductive system, such as cervical cells, the epigenome of the cervical cells share any epigenetic changes.

"In the cervical cells, changes in the cells' epigenomes do not drive cancer formation but can be used to identify women at risk of cancer," Widschwendter concluded.

Can current models predict ovarian cancer?

Vasilev said most of today's ovarian cancer screening models are based on older technologies of ultrasound, family genetic history and various tumor marker blood tests that are nonspecific for screening purposes.

"Genetics and epigenetics research is making inroads into the development of a more accurate method of screening," Vasilev said. "To date, the standard recommendation is not to screen women at average risk for ovarian cancer due to the poor accuracy of these tests and models."

Screening high-risk women based on family history, ethnic background or genetic testing for BRCA mutations, for example, is not very effective, either, although it is often recommended.

"Because of this lack of sensitive and specific tests and models, three out of four ovarian cancer cases are diagnosed in late stages, usually beyond cure," Vasilev stated.

"Only around 12 percent of all ovarian cancers develop in BRCA mutation carriers," Widschwendter added. "We hope that the 88 percent remaining ovarian cancers can be predicted by tests like the WID-OC, so that we can offer these women a chance to reduce their cancer risk."

Is it likely this technique will be used?

As Widschwendter stated, it's believed the WID-OC test may be able to identify at-risk women in advance of their ovarian cancer diagnosis, though this has not been accomplished yet. The only way to achieve this goal is to collect cervical samples from a large population of many thousands of women, then wait for several years to identify any women who had developed ovarian cancer.

"We would analyze samples from women who had or had not developed cancer and determine whether the WID-OC test could have predicted which women developed ovarian cancer," Widschwendter explained. "We are working on the logistics and funding for this large-scale initiative at the moment."

"This is a promising avenue of research that is in line with other genomic and epigenomic research, which will help get us to a viable screening strategy, hopefully, sooner than later," Vasilev concluded.

The future of detecting and treating ovarian cancer

According to Widschwendter, 75 percent of women with ovarian cancer are diagnosed when their tumor has spread within the abdominal cavity or beyond, and more than 50 percent of ovarian cancer patients die within five years after their diagnosis.

"Currently, we have nothing effective for early diagnosis," Vasilev said. "Treatment is a whole other story, but early ovarian cancer can often be cured with surgery alone. Therefore, early detection is high on the list of helping improve ovarian cancer survival rates."

"Our goal is to identify women at risk for ovarian cancer independently of a BRCA mutation, so that all women can make choices to minimize their chances of being diagnosed with advanced-stage ovarian cancers by either applying primary preventive and/or early detection measures," Widschwendter stated.