A Short(ish) History of Birth Control

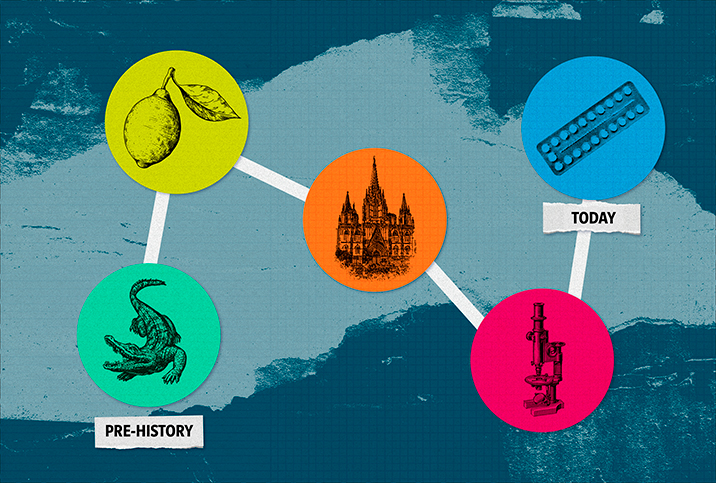

For as long as people have been giving birth, there have been people trying their damndest to avoid having babies. Birth control has taken on a multitude of forms and methods across every society across all of human history—to relate them all would be impossible, though several lengthy books have tried.

In the developed world, it can sometimes feel like most of the history of reproductive rights is just that—history. Nevertheless, the recent judicial decision in Texas banning abortions after six weeks or the revelation that Britney Spears' conservatorship included a forced contraceptive shows us that the past isn't really all the way past. The age-old struggle of childbearing individuals to maintain control over their own body continues today.

Moreover, the long and storied history of contraception illustrates how birth control is not a modern indulgence but a fundamental human necessity—one that has always been intimately intertwined with not just gender and sexual rights, but questions of racial, economic and political justice.

What is birth control?

Today, birth control is often colloquially used to describe contraceptive pills, but really it refers to any method (however effective) intended to prevent conception and pregnancy, from abstinence to "the pull-out method" to condoms.

Abortion, though falling under "reproductive rights," is not considered birth control per se, and much of the history of abortive methods and rights has been omitted from this particular narrative. But since no birth control method (except abstinence) is 100 percent effective, the history of abortion is inextricably tied to the history of birth control, and both will sometimes pop up in our story side-by-side.

Legendary groupie Pamela Des Barres opens up about using birth control as an expression of feminism in the 1970s. Watch the full interview here.

Prehistoric Era: Pretty much magic

In the Grotte des Combarelles, there is a prehistoric cave drawing dating back to at least 12,000 years ago that appears to show a man wearing a cover of sorts over his genitalia. Some, like author and professor Aine Collier, have speculated this represents a primitive condom, though its purpose—whether prophylactic, contraceptive or ceremonial—is unknown.

According to an extensive history of birth control assembled by Planned Parenthood, many Stone Age people didn't understand the link between intercourse and pregnancy. Some folks thought that certain fruits contained the spirits of children, while others believed that pregnancy was ruled by the sun, wind, rain, moon or stars.

Family planning becomes pretty much impossible if you believe, like these Stone Age lovers, that pregnancy is basically "a magical event." But for ancient people who did understand the connection between sex and pregnancy, abstinence was likely one of the earliest forms of contraception.

The Ancient World: Crocodile poop, lead and sneezing

Some of the earliest evidence of deliberate birth control and abortion was found on two ancient Egyptian medical scrolls, the Kahun Papyrus (1250 BC) and the Ebers Papyrus (1550 BC). An account from the Ann Arbor Sun describes the various birth control methods outlined in the ancient texts.

The Papyri recommend various pessaries—vaginal suppositories—made from an abundance of odd substances, including honey, sodium carbonate, crocodile dung and lint moistened with acacia juice. The efficacy of these methods is mixed; acacia is actually a component of some modern spermicides, for example. Crocodile dung—no doubt dangerous to both collect and stick inside you—has produced inconclusive results in modern tests.

The ancient Greeks also included contraceptive methods in their medical records. Aristotle recommended putting both cedar oil and olive oil in the vagina to slow sperm. Soranus, a Greek gynecologist, recommended several strange contraceptive techniques to his patients, including sneezing and squatting after sex to expel the semen from the vagina.

In ancient China, a popular treatment among women was drinking highly poisonous cocktails containing lead, mercury and/or arsenic. While this did, in fact, cause sterilization, it caused a host of other issues as well, including kidney failure, brain damage and death.

Contraception also makes a brief appearance in the Old Testament—Genesis tells the story of Onan, who spilled his seed on the ground to avoid impregnating his sister-in-law. Technically, this is coitus interruptus (aka "the pull-out method"), but poor Onan, in addition to being killed by God, would also be forever associated with self-gratification.

The Middle Ages: Weasel testicles, wolf pee and the church

As the influence of Christianity grew during the Middle Ages, early Christian attitudes began to inform how contraception was practiced, controlled and discussed in Europe. The church's official position on contraception and attempted abortion was that it was a sin, punishable by exile from the church or even death.

Much of the contraceptive knowledge from this era was therefore spread through word-of-mouth among networks of women, according to scholar John Riddle. Herbal concoctions, including rue, lily root, fennel and celery seeds, were common, while Queen Anne's Lace was used as something of a primitive Plan B. Coitus interruptus, of course, continued to be popular, as was extended breastfeeding after birth—a practice that today is recognized as a pretty successful method of birth control.

Other practices were probably less successful. The use of contraceptive amulets was widespread in the Middle Ages, according to Planned Parenthood history. Medieval magicians recommended women wear weasel testicles, desiccated cat livers and hare anuses, to name a few. Lore also suggested walking three times around a spot where a pregnant she-wolf had urinated to avoid pregnancy.

The Pre-Industrial Era: Lemon peels, diaphragms and linen condoms

Much of contraception between the Middle Ages and the late Modern era remained a mix of surprisingly effective folk medicine and mostly useless folklore. As awareness of venereal disease spread, however, condom use became more common, and with it came some awareness of their contraceptive potential.

One extensive account comes from Giacomo Casanova, the famous womanizer of the 1700s, detailing his numerous experiments in contraception. His amorous memoir, "Histoire de Ma Vie," describes techniques such as inserting an improvised diaphragm made from half a lemon peel into the vagina, as well as the use of linen and animal sheaths to avoid "a certain fatal plumpness." While some worried that their seed would cause them stress, others had a more serious concern.

In America, contraceptives and abortive methods were widespread among black slaves seeking to spare future children from the horrors of slavery. Slaves brought "botanical lore from Africa," according to historian Janet Farrell Brodie, a medicinal practice that included instructions on which plants to consume to avoid or abort the pregnancy.

The Industrial Era: Obscene rubbers

In the early 19th century, one of the most popular contraceptives was Edward Bliss Foote's rubberized pessary called the "womb veil," a precursor to the modern diaphragm. In the mid-19th century, Charles Goodyear invented vulcanized rubber, which, according to medical historian Mike Magee, "was more moldable, mechanically stronger, and all importantly, less sticky" than natural rubber. This discovery was soon followed by the widespread proliferation of...well, "rubbers."

But advances in contraception were quickly hamstrung by a cultural backlash. In 1873, an anti-obscenity campaign spearheaded by stick-in-the-mud and dry-goods salesman Anthony Comstock led Congress to pass the Comstock Act. Congress ruled that contraceptives were "obscene," making it a federal offense to distribute birth control through the mail or across state lines.

The Early 20th Century: Eugenics and Margaret Sanger

The history of birth control science is not entirely a story of steady progress toward women's agency over their own body. For much of the early 20th century, it was the exact opposite.

Eugenics was first proposed as a new (pseudo) science in the late 1800s. British scholar Sir Francis Galton—Charles Darwin's half-cousin—campaigned to improve the human race by ridding human society of its "undesirables." Though it never truly took hold in Galton's home country, eugenics gained popularity in America during the early 20th century.

"Birth control" took on a darker meaning as U.S. legislatures passed laws allowing for the forceful sterilization of thousands of Americans possessing "undesirable" traits, including criminals, the poor, the sick, the mentally ill and people of color.

The legacy of America's eugenics continued well into the 20th century. Adolf Hitler spoke admiringly of the United States' eugenics practice and modeled his own forced sterilization programs after them. In America, involuntary sterilization of indigenous people and inmates of mental institutions would continue as late as 1976.

'Birth control' took on a darker meaning as U.S. legislatures passed laws allowing for the forceful sterilization of thousands of Americans possessing 'undesirable' traits, including criminals, the poor, the sick, the mentally ill and people of color.

Much of the progress in reproductive rights in the early 20th century is attributed to a single woman, socialist and feminist activist Margaret Sanger. As an advocate for birth control, Margaret Sanger was a staunch opponent of the Comstock Act and frequently faced legal repercussions under its purview.

In 1923, Sanger was incarcerated for starting the Birth Control Clinical Research Bureau and the American Birth Control League, two organizations that eventually merged to become Planned Parenthood. In the decades to come, Sanger's activism would lead to the slow rollback of the Comstock Act and the development of the first birth control pill.

Despite her pivotal role in the fight for birth control, Sanger's legacy is darkened by her association with the eugenics movement of this era. Medical historians have argued that eugenics was secondary to the humanitarian motivations behind Sanger's advocacy—some even going so far as to suggest her association with the movement was almost entirely political maneuvering. Whatever Sanger's motivation, today Planned Parenthood has officially denounced Sanger's eugenist views.

The Late 20th Century–Today: The pill and beyond

The next seismic shift in birth control history came in 1960, when the first oral contraceptive, Enovid-10, was approved by the FDA, according to another history from Planned Parenthood.

Enovid-10 used synthetic hormones progesterone and estrogen to repress ovulation in women. The first version of Enovid—which had a dose of hormones nearly 100 times higher than modern birth control—had rare but serious side effects that were ignored or missed during dubious clinical trials. Nonetheless, for most American women, the pill proved a reasonably safe and nearly 100 percent effective form of contraception.

Previously, the most effective form of birth control—condoms—had put most contraceptive power in the hands of male partners. The pill gave access to reliable, (mostly) safe birth control to women for the first time in human history. Results were swift and dramatic, according to Planned Parenthood, since the development of the pill: "Maternal and infant health have improved dramatically, the infant death rate has plummeted, and women have been able to fulfill increasingly diverse educational, political, professional, and social aspirations."

The pill gave access to reliable, (mostly) safe birth control to women for the first time in human history.

After the pill, the hormonal birth control industry boomed and a wealth of new products hit the markets in the coming decades. In the 1980s, the FDA approved the first copper IUD, Paragard, followed by Norplant, the first long-acting contraceptive implant, in 1991. In the late '90s, the first emergency contraceptive (aka "the morning-after pill"), Preven, hit the shelves.

In 2010, the Obama administration enacted the Affordable Care Act, a provision of which mandated that employer insurance cover contraception, greatly increasing access to affordable birth control for millions of Americans. During the presidency of Donald Trump, however, ACA mandates were significantly weakened, as laws were passed allowing employers to refuse to pay for employee contraceptives due to religious or moral objections.

All of which leads us to today, when the story of Britney Spears bears eerie echoes of the forced contraception of the eugenics movement, while Texas' abortion ban and Trump's ACA rollback are both haunted by medieval Christian attitudes. Timelines may make for easy article structure, but the complex history of birth control—like so much of history—falls backward as much as it moves forward, mixing stories of liberation and subjugation in equal measure.