Eating Disorders Can Affect Your Sex Life

When we talk about harms associated with eating disorders, body weight is often the first topic to arise. Anorexia nervosa (AN), for example, can be a visually shocking disease as people affected sometimes become dangerously thin.

However, not everyone with AN reaches that point, especially during the onset of the disorder. AN is simply defined by an intense fear of gaining weight as well as extreme measures one takes to suppress weight gain. What's more, people with other eating disorders, like bulimia nervosa (BN) and binge-eating disorder (BED), often stay at a weight that's considered normal.

More than just weight alone, disordered eating can have real long-term health implications. Every organ system in your body can be affected by an eating disorder, leading to anything from constipation to esophageal rupture to heart failure. Eating disorders have one of the highest mortality rates among psychiatric conditions.

The physical and mental health implications of eating disorders are truly devastating. But what's not talked about as much, said Zach Verwey, M.A., LPC, NCC, a therapist based in Denver, Colorado, is how these behaviors affect sex and intimacy.

"Eating disorders have everything to do with physicality, being in our bodies, self-esteem, shame and sensuality," he said. "Our sexuality is bound to be impacted if we are struggling with an eating disorder."

"Think of it as a chain-link fence," said Sam Louie, M.A., a therapist based in Seattle, Washington. "There are all kinds of things that can be interrelated when we talk about eating disorders."

Physiological effects

Before we separate physiological and psychological effects, Cynthia Bulik, Ph.D., founding director of the University of North Carolina Center of Excellence for Eating Disorders, said it's important to remember that both tend to occur together, as well as perpetuate each other.

For example, prolonged low weight is often seen in anorexia nervosa, which can lead to decreases in sex hormone levels—such as lower testosterone in men and lower estrogen in women.

"On a basic biological level, lower levels of these hormones can reduce sex drive and sexual responsiveness," Bulik explained. "With this can come less lubrication in women, as well as [more difficulty] to become aroused and/or reach orgasm regardless of sex and/or gender identity."

Prolonged low weight in women can lead to irregular menstrual cycles (oligomenorrhea) or the complete loss of a period (amenorrhea). Although these cycle changes can also contribute to lowered sexual desire and arousal, Bulik is careful to mention that they do not indicate infertility.

"Many women with amenorrhea think they are protected from becoming pregnant," she said. This is mistaken thinking. "In fact, you can still be ovulating even though you are not menstruating."

Or, if someone with AN is in the process of gaining weight during recovery, ovulation can occur before their periods return.

'The impacts of eating disorders on sexual functioning and intimacy can vary greatly by person, but disordered eating is still likely to increase the risk.'

Either way, with anorexia nervosa, menstrual cycles should not be the bona fide way to tell if you're pregnant. In a 2010 study, Bulik and colleagues found that their participants with anorexia nervosa had a higher rate of unexpected pregnancy and clinical abortion than women without eating disorders. This is of clinical concern, they wrote, because absent or irregular menstruation may be misinterpreted as decreasing the risk of pregnancy.

"Being amenorrheic is not contraception," Bulik emphasized.

At the same time, many women who experience prolonged amenorrhea and/or oligomenorrhea may have difficulty conceiving when they do decide they want to become pregnant.

"So infertility can be a persisting problem that they encounter even after recovery," Bulik said.

Despite these links, it remains hard to know how eating disorders will affect any given person's physiological responses to sex, sexual desire and menstrual cycles.

"The impacts of eating disorders on sexual functioning and intimacy can vary greatly by person," Bulik explained. "But disordered eating is still likely to increase the risk."

"Eating disorders can happen at any size," Bulik added, "so we need to remember we are talking about ranges from severely underweight to people living in very large bodies."

Psychological effects

In addition to and perpetuating the physiological can be the psychological. Bulik noted that body image concerns are often the last symptom to resolve in eating disorders, even if the individual has recovered from harmful eating and exercise patterns.

That is, if someone's dislike, disgust or shame toward their body, regardless of actual body shape or size, persists, they can still have a hard time cultivating a fulfilling sex life. Body dissatisfaction and/or body image distortion can lead someone to avoid sexual activity altogether or not be present while having sex.

"One partner we worked with in our couple-based treatment said, 'It always feels like there are three people in bed: Her, me and her eating disorder,'" Bulik said.

"There can also be considerable shame associated with having others see or touch their body, with every action being a reminder of how dissatisfied they are with their weight and shape," Bulik added.

Further, many people who go on to develop eating disorders have usually gone through stressful life events, such as childhood sexual and/or emotional abuse, which can lead to foundational problems with intimacy.

Childhood abuse, Louie noted, doesn't always look like what we might imagine. He has seen clients who were never physically abused as children, but who experienced or sensed that they may have been objectified. For example, if they looked different from everyone else in their town—say, due to ethnicity and/or skin color—and felt unsafe or objectified for it, it can all build into what Louie described as, "The creepy icky feeling that got them fixated on what they have to look like."

"Those who do have a history of sexual abuse or any sort of trauma can face additional challenges with post-traumatic reactions, lack of trust, and other trauma reactions that adversely influence their relationships," Bulik said.

Eating and sex behaviors can mimic one another

To understand the psychology of eating disorders and sex in a different way, Verwey offers an additional perspective: "Food and sex have historically always been linked."

Certain foods, like chocolate, are "sexy." There are entire industries built around "food porn," and we can feel desire for food as well as other people.

"When you have a distorted relationship with food, for whatever function that might be serving, your relationship with sex is going to follow suit in some way," Verwey said.

More than just "following suit": Verwey said the two—eating and sex attitudes/behaviors—can mimic each other.

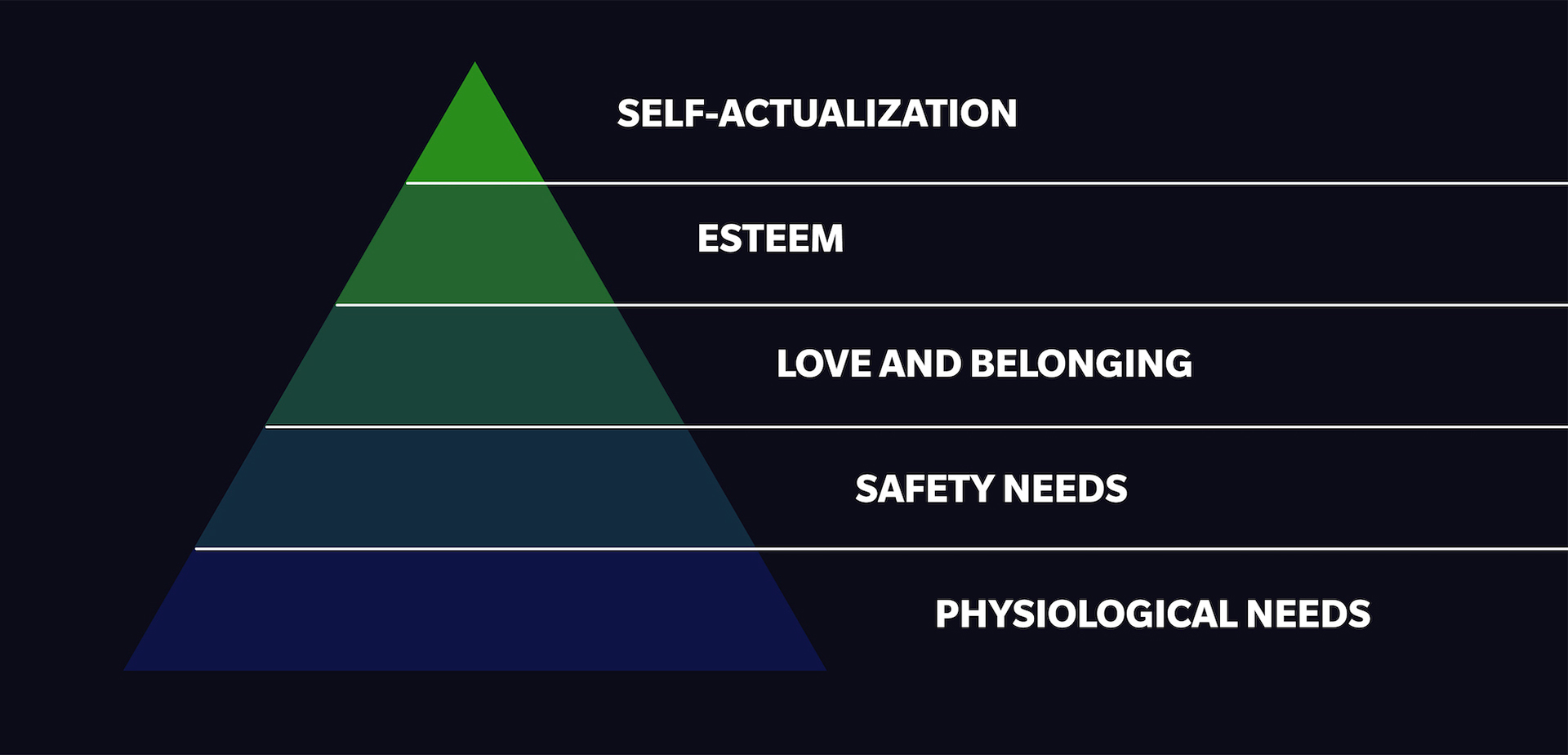

Take Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs. This theory categorizes human needs into five levels, from the most basic physiological needs (food, shelter, reproduction, etc.) to higher levels of self-actualization. To progress to the higher levels, the lower levels need to be adequately satisfied first.

Eating and sex, Verwey said, are both on the bottom and most primal layer.

"When you have gotten accustomed to distorting one of those needs or using it for another purpose, such as to feel control or to numb oneself, very naturally, that is going to translate into that other need as well," he continued.

In his own research and work, Verwey focuses on how issues of disordered eating and sexuality impact LGBTQIA+ individuals. Through this, he said, anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa-related behaviors tend to coincide with specific attitudes toward sex.

Those who exhibit more AN-related behaviors, he noted, tend to be more restrictive with sex, use it to numb themselves, and/or prioritize cleanliness and purity during intimacy. These patterns seem to reflect the restricted caloric intake and excessive "orderliness" that characterizes anorexia nervosa.

For those in the bulimia range, Verwey added, sexual activities and behaviors may be more impulsive and self-destructive, as if mimicking the binge-purge cycle.

Bulik sees similar patterns in her work.

"Much like their binge-starve cycle, some [patients] actually experience periods or patterns of more impulsive sexuality," she said. "This can bring about a host of risky behaviors, such as unprotected sex with strangers, binge drinking and drug use."

As for people with binge-eating disorder, studies also point to issues with sex and sexuality, although more research is needed.

Treat the eating disorder, treat the intimacy

Any compulsive or addictive behavior, such as those around food, exercise and/or purging, can play into intimacy disorders.

"The lack of true intimacy—where an individual does not feel emotionally safe—leaves one vulnerable to develop addictive tendencies as a means to cope," Louie wrote for Psychology Today.

People can use a substance or behavior to keep somebody at a distance, which doesn't have to mean they're not in a relationship, or that there's physical distance.

"There's an emotional gulf between the two," Louie said. "The behavior and/or substance is a way to help the individual keep that distance."

The individual might not even consciously want distance, but something has happened—perhaps a past trauma—that led them to doubt their safety in intimate relationships.

In private practice, Louie tries to get at the central intimacy-related fears of his patients who exhibit behaviors like disordered eating.

"We're trying to strip all that away," he said. "What exactly are the real fears? Being known? Being accepted? Being judged?"

In Bulik's work, she finds that many people with eating disorders "can and do recover and develop rich and satisfying intimate relationships." However, she noted, sexuality remains a challenge for some.

To treat eating disorders, Bulik and colleagues developed Uniting Couples in the Treatment of Eating Disorders (UNITE). The idea came after the recognition of how including partners in therapy could benefit the individual and their relationship.

"We deal with intimacy topics directly in the therapy, allowing us to work with both the patient and their partner and fully understand the experience of each regarding the eating disorders, their relationship in general, and their sexuality and intimacy," she said.

The couple-based intervention is still emerging and aims to offer an alternative to traditional treatment assumptions. Therapy for eating disorders, Bulik and colleagues noted, is "often only designed for the individual with the disorder despite partners being negatively affected and typically wanting to help in an effective and loving way."