Colorado Is the First State to Ban Anonymous Egg and Sperm Donations

In 2025, Colorado will become the first state to abolish anonymous egg and sperm donations. Senate Bill 22-224 allows donor-conceived individuals to discover their genetic parent's identity after turning 18. The new legislation is the first of its kind and will undoubtedly affect the lives of children born with the help of assisted reproductive technology (ART).

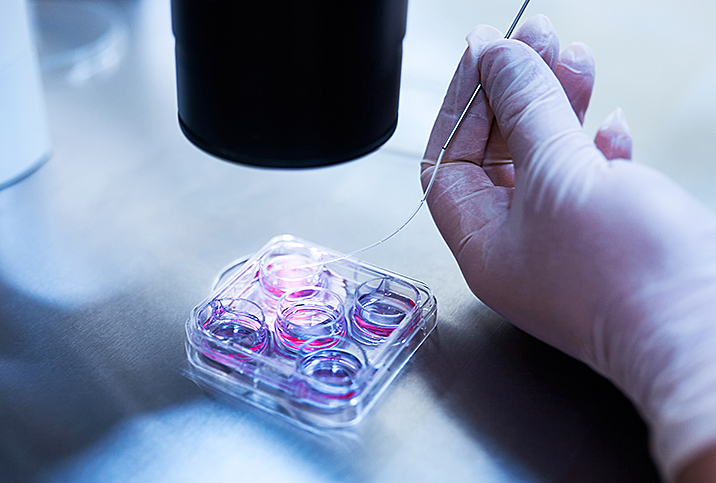

The number of people who use ART is on the rise, but it's largely unregulated territory. Several recent lawsuits detail serial sperm donations, fertility fraud and lack of federal oversight other than screening for communicable diseases.

Colorado's legislation, signed in May 2022 and effective starting in 2025, is unique. Five states have enacted the Uniform Parentage Act (UPA) of 2017, where donor-conceived individuals can request the identity of their genetic parent when they turn 18, but it's optional for donors to agree. Several other states have pending UPA legislation, which was amended in 2017 to include same-sex parents and other provisions protecting assisted reproduction.

Advocates say Colorado's new legislation will support donor-conceived people with bolder safeguarding.

"The Colorado law is an important step in the right direction because it recognizes that donor-conceived people have rights and interests that deserve protection," said Erin Jackson, a San Diego resident and CEO and president of the U.S. Donor Conceived Council, a catalyst behind the new legislation.

S.B. 22-224 ensures that a sperm donor can contribute to only 25 families. The bill also limits the egg donation retrieval process to no more than six times, which is consistent with the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) guidelines.

The new legislation also ensures that donors and the families who use donors are on the same page.

"The CO bill will change the discussion about donation so that donors understand the impacts of their donation," said Gina Davis, M.S., the founder and certified genetic counselor at Advocate Genetics, an Elk Grove, California, company that backed the legislation.

The impact of knowing your medical history

Knowing your medical history is indispensable. Accessing the genetic parent's medical records can help donor-conceived individuals comprehend their own medical history and be aware of any potential risks for their own children.

"Research consistently shows that many donor-conceived people need to know the identity of their genetic parent for a variety of reasons, including wanting a more complete picture of their own identity. The law also requires donors to provide regular medical updates, which could be lifesaving for the people conceived via their donations, and their children," Jackson said.

"Many donor-conceived adults do not have any medical history information [for] about half of their biological relatives, which can cause anxiety and put people at an undue disadvantage regarding medical care and treatment," she added.

A complete medical history can be lifesaving, especially regarding early detection, prevention, and spotting pertinent symptoms you know are in your history.

"From a health perspective, as we chip away at the genetic and environmental causes of disease, the long-term communication of family medical updates has become indispensable to health management. It can often lead to testing, early diagnosis and preventive management for at-risk individuals," Davis said.

A lack of access to this critical information can significantly impact medical care for people, Davis pointed out.

"This includes most donor-conceived people, because of decades of reliance on non-identified gamete donation," she explained.

Donor-conceived individuals have a host of other reasons for wanting to know their genetic parent's identity, such as curiosity about who they are, what they look like or to show them how they turned out as a person.

In a 10-year study from the Sperm Bank of California, adult donor-conceived people from 256 families were eligible to receive identifying information. One-third of the individuals wanted to know their genetic parents because they were curious about their identity. The most common reason was that people wanted more information, including medical histories.

Anonymity doesn't exist anymore

The nature of using assisted reproductive technology is evolving, moving away from a past of secrecy and shame.

A 2017 study stated that since the beginning of donor conception, families have largely utilized secrecy and partial disclosure. Respondents in the study who found out they were donor-conceived later in life mainly felt deceived. The study concluded that knowledge of being donor-conceived is essential and a donor's anonymity is double concealment, first in the child's family and then with their genetic parent.

"Studies show that when parents are open with their children by the age of 4 about their birth story, that they adapt and adjust well and have stronger and healthier relationships. No longer is donation a 'family secret,'" said Lisa Stark Hughes, president of Gestational Surrogate Moms, another California company behind the Colorado legislation.

"Hopefully, the CO law will encourage recipient parents to be open with their children from a young age, so donor-conceived people no longer feel like they have been lied to their whole lives after finding out from a home genetic test or while trying to decipher their medical issues," Hughes stated.

A complete medical history can be lifesaving, especially regarding early detection, prevention, and spotting pertinent symptoms you know are in your history.

In the age of DNA tests that ship to your front door, anonymity no longer exists. The chances of someone finding out they are donor-conceived, even if their family kept it secret, are more likely now than in the past.

"State regulation helps to establish thoughtful guidelines that will facilitate more appropriate communication of medical and identifying information for donors, recipients and donor-conceived people," Davis said.

While no other state is considering legislation like Colorado's yet, U.S. Rep. Chris Jacobs, R-N.Y., recently introduced House legislation requiring sperm banks to collect more comprehensive medical information from their donors. The bill, Steven's Law, is named in honor of Steven Gunner, who died at age 27 due to an opioid overdose and battle with addiction and schizophrenia. After his death, his parents learned that the donor used to conceive him had also been diagnosed with schizophrenia and struggled with addiction, according to Jacobs' website.

"Hopefully, the CO bill will encourage more open donations so that donor-conceived people can have a more accurate family medical history and recipient parents can be more open about their family-building story," Hughes said. "Using a donor to build your family should not be a family secret. It is time to let that go."