Environmental Racism's Toll on Reproductive Health

In the 4-square-mile Ironbound community of Newark, New Jersey, environmental activists advocate against the construction of a new power plant.

The Ironbound community is home to 50,000 residents and faces terrible air quality caused by two existing power plants, congested diesel truck traffic, an incinerator and one superfund site, The Diamond Alkali Superfund. A superfund site is an abandoned toxic waste site that requires a cleanup response due to hazardous materials and conditions.

During Superstorm Sandy, 8 million gallons of raw sewage flooded into Newark Bay after the Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission (PVSC) lost power, prompting plans for the backup power plant. PVSC's plans for the plant were not solar- or wind-powered and would dump more greenhouse gasses into the already polluted air.

It's no surprise that Ironbound community residents face health consequences due to pollution, including high childhood asthma rates: 1 in 4 children in Newark has asthma, which is three times higher than the national average.

'The reproductive health conditions of a grandmother will be passed on genetically to their granddaughters.'

And it's not just asthma—the people of Newark face reproductive health challenges, as well. A 2017 Community Health Assessment found the rate of infant mortality is higher in Newark than anywhere else in the state of New Jersey. Further, Black infants are twice as likely to die than white infants.

"Considering poverty and access to health care as barriers and added detriments, these sites of toxic pollution are silent and slow killers," said Jessica Valladolid, an environmental justice organizer with Ironbound Community Corporation, an organization that serves the Ironbound community.

The effects of pollution on reproductive health last for generations, Valladolid explained. "The reproductive health conditions of a grandmother will be passed on genetically to their granddaughters."

Newark is one example of the inextricable link between environmental racism and reproductive health.

Environmental racism and health inequities

Environmental racism is the disproportionate effect of hazardous environmental conditions on communities of color. It is a global issue causing reproductive health problems for birthing people, infants and communities.

Climate change exacerbates health challenges. A 2021 report by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) concluded that Black and African American, Hispanic and Latino, American Indian and Alaska Natives, and Asian individuals are most likely to live in areas with the highest impacts of climate change.

"At the intersection of environmental justice and reproductive justice is the right to parent in a safe and healthy environment," said Taylor Morton, director of Environmental Health & Education at WE ACT for Environmental Justice.

For pregnant people and their babies, hazardous environmental conditions can stem from poisoned water, polluted air or exposure to heavy metals. "It's important to note that there is a cumulative impact when exposed to multiple environmental hazards, as is often the case in these communities," Morton said.

"The reproductive justice movement came about because if you can't access a right, do you really have it?" explained Tracey J. Woodruff, Ph.D., M.P.H., a professor and director of the Program on Reproductive Health and the Environment at the University of California, San Francisco.

Woodruff explained that one example of environmental racism is redlining—a racist housing policy that outlined Black, Brown and immigrant communities as hazardous, warning mortgage lenders to deny them services. The New York Times reported that formerly redlined areas are 5 degrees hotter than non-redlined neighborhoods, frequently have fewer trees, and are home to more paved surfaces, such as highways, which trap and radiate hot air. Similarly, "sacrifice zones" are areas with hazardous chemical pollutants situated near heavily polluted industries, typically inhabited by low-income residents and people of color.

According to a 2018 study in the American Journal of Public Health, Black people are exposed to pollution at 1.5 times the rate of the rest of the American population.

"Studies also show that Black, Brown and Indigenous communities and low-income people face disproportionate harms from pollution and chemicals, and those exposures are linked to a litany of health harms, including premature birth and low birth weight, that have ramifications across the life span," Woodruff said.

Air pollution on reproductive health

Newark is fighting to breathe clean air, Valladolid said.

Research published in the October 2021 International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, co-authored by Woodruff, makes the connection between climate change and reproductive health alarmingly clear.

Air pollutants lead to lower fertility and live birth rates, adverse birth outcomes, and higher rates of miscarriage, preterm birth and low birth weight. Further, a 2018 study cited by Woodruff noted that proximity to major roadways increased the risk of infertility among nurses in the U.S.

A 2017 study also in Woodruff's research suggested that for 1.1 million live births, the risk of low birth weight was higher within 3 km of a fracking site and increased by 25 percent within 1 km of a site. Meanwhile, a 2022 study indicated exposure to wildfire smoke while pregnant leads to preterm birth.

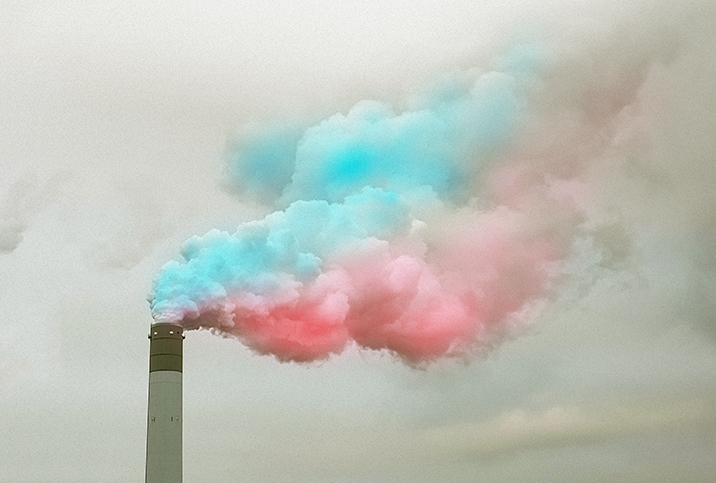

Rising temperatures, declining fertility

Rising temperatures have detrimental consequences on reproductive health, such as fertility and preterm birth. National Partnership's site lists that Black or Hispanic women with heat exposure had double or more the risk of preterm birth or stillbirth.

"Complications from extreme heat can be much harsher on mothers and pregnant people," Morton said. The aforementioned research connects that women and birthing people are more vulnerable to climate change because of their social status and family responsibilities. Temperature extremes also cause droughts and floods and lead to food and water insecurity, heightening maternal and infant stress, and safety and health issues.

Rising temperatures mean more heat waves; heat waves can mean more hospital visits. Overcrowding in hospitals due to rising temperatures impacts those who need reproductive services. The number of physicians is also typically lower in low-income areas.

Pregnant people are likely to have premature, underweight or stillborn births due to the "heat island effect" (higher temperatures in concrete jungles, where there is limited green space), Valladolid explained.

Woodruff added that people in low-income housing might not have access to AC, water or shade to help alleviate the heat. "All of these things—heat, flooding, neighborhood contamination—are linked to health harms, and those hit low-income communities disproportionately," Woodruff said.

Mitigating impact

"There is power in policy," Valladolid stated. New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy signed the Environmental Justice Law in 2020, intended to protect overburdened communities from further harm—the law's rules are still in development.

Murphy did halt the vote on the impending power plant in the Ironbound community and called for a more thorough review of the environmental impacts. The hope, Valladolid said, is that any development would include community input in creating solutions.

To help mitigate the impacts of climate change, Woodruff works on translating the science for policy change. "One of the biggest challenges is that EPA does not always use the best science or most up-to-date methods to evaluate chemical risks, and that means people are often left unprotected from harmful chemicals," Woodruff said.

"We have been very focused on EPA's implementation of the updated Toxic Substances Control Act," Woodruff continued. "That is the law governing how chemicals are evaluated for health risks and other harm. It took 40 years to update the law, which was signed in 2016, and it was supposed to make it easier to ban harmful chemicals, but it hasn't worked out that way. The updated law gave EPA new tools to restrict these harmful chemicals, but if the agency doesn't use them—that's a problem."

"If we can't have clean air, water and healthy food, then our reproductive health is at risk," Woodruff concluded.