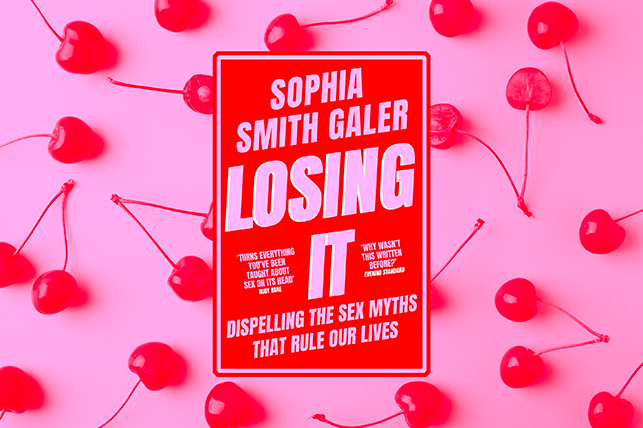

Between the Pages: 'Losing It' Relies on Sex Facts and Not Fiction

Author and journalist Sophia Smith Galer believes the world needs reformed sex education based on facts rather than fiction. As a former BBC religion reporter, Smith Galer often reported on the role that dating and sex have in people's lives. Being a pioneer in TikTok journalism, she's had a lot of conversations with young people about sex education.

"I think we all carry these personal archives of where we've somehow been failed in sex education," she recalled.

Smith Galer is a multi-award-winning journalist who made both the Forbes 30 Under 30 and Vogue's 25 Most Influential Women in Britain lists in 2022.

Her debut book, "Losing It: Sex Education for the 21st Century," debunks sex myths and promotes sexual freedom. It also investigates the harm that false information has caused, as she offers many steps to move forward in fighting "the sex misinformation crisis."

In this exclusive interview with Giddy, Smith Galer discusses consent, virility and how sex ed could be improved.

Editor's note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why did you decide to write a book about sex?

Smith Galer: When you ask people how their sex ed was, they never normally say anything positive. And, on a personal level, I'd been there thinking, how do we all just accept that? How is it a norm that sex education is bad when it's so important to our adult lives? All the conversations we have about dating and sex, but equally, all the harms that come about from not feeling fully informed.

I put my journalist hat on and started looking at the available research on sexual behavior and health education. I realized the statistics show a pretty miserable picture for all of us. It could be so much better if our sex education was far broader and the information about sex we had access to throughout our lives was better and based on evidence.

Your book is based on myths. Why was it so important to address them?

We know that not only in the English language but even more so in the non-English language information around sex, there is a lot of misinformation online and, indeed, offline. Lots of us are raised with social or gender norms about sex that are entirely inaccurate. To name a few, the idea that sex is painful or it's normal for sex to be painful for women. That would be an example of a myth that actually has no evidence base. It may be common because of societal failures, but it's by no means normal, right?

I begin with the virginity myth in the book because if you think about it, it's wild that we still use the term "virginity," "lost your virginity" or "virgin." Or that the state of sexism—especially still in women—is something fetishized in many communities around the world. Equally, people feel a stigma about when they have sex for the first time and how they define that sex instead of looking positively. Early sexual health is a journey and a set of experiences where, hopefully, you grow, learn and have a good time.

Instead, it's viewed as a one-time thing that will change my status and my identity of who I am. That's just a really myopic way of looking at sex, which causes damage to people. We can be far healthier with how we talk about first-time sex.

Sometimes myths are dangerous in that you wind up spending money on something you didn't need to and you cause yourself damage from spending money on it, such as a vaginal tightening wand. It may be that your belief in the virginity myth means you ostracize someone in your community because you've learned they've had sex with someone. Belief in some sex myths could make you cause harm to a sexual partner or may make you so depressed you want to take your own life. The harms you may chart from sex myths are innumerable and wide-ranging.

In the consent myth chapter, you mentioned that sex education in the United Kingdom has a long history of 'can'ts' and not 'cans.' What should be the approach to consent for both men and women?

I think the approach goes back to the crux of why you were teaching sex ed. If you're teaching sex ed so young people don't get STIs [sexually transmitted infections], don't get pregnant as teenagers or have unintended pregnancies as adults, and that they don't commit assault or become a victim of assault, you're teaching them a tiny fraction of sex. You are not teaching them to feel like they deserve control over their sex lives, what they want for themselves or the vocabulary to ask for what they want. I'm talking about really wide-spanning communication with your partners about equity in relationships and sex, which is far more expansive than that.

We need to start from a place where we teach sexual autonomy. Can a woman truly say yes to sex when 37 percent of people in the U.K. mislabeled the clitoris on a female reproductive anatomy diagram? So many of us have not been taught to have sexual autonomy over ourselves that when we do say yes or no to sex, we're not fully informed. We're also not told about normalized coercive behaviors in society, how to deal with them and how to be empowered enough to challenge them.

Sexual autonomy is the baseline. Once you've got young people with good information about sex, with good self-esteem, that will protect them for their entire adult lives. That's when you introduce, "OK, here's what to do if someone sees your sexual autonomy and thinks, no, I have control over your body, not you," and then you introduce those ideas. And it's a really long, complex journey that takes years and years, which is why we have really long sex ed curriculums in most parts of the world.

When covering the virility myth, you talked about what happens when sexual accomplishment and masculinity are considered one. How does this affect less experienced men?

Research in this area is still nascent. But what we know is that little has been done on young people who identify as older virgins, which, historically, has been something men seem to have been a little more concerned about as a sort of social status than women. Feeling out of sync with your peer group is likely to lead to lower mental health. We know young people who have a negative first sexual experience are more likely to have a negative sexual function and possible dysfunction into their adult lives. There is so much stigma around the attachment between masculine identity and sexual activity.

We've gotten much better as a society talking about depression and anxiety, and it's been hard enough to stimulate that conversation amongst men, for whom it is a crisis. We now need to get a lot better at talking about the stigma of virginity and not perpetuating it. We need to lose that word from our vocabulary and understand that everyone starts having sex at different times, when they are ready, have achieved sexual autonomy and are mature enough to act upon it.

We also need to not judge people for their sex lives. To truly have a sex-positive world and our sexual rights, we deserve the right to not be judged for how and who we have sex with, so long as we're not causing harm to ourselves or others. And the right to not be judged is not a right we have access to in 2023. We've gotten a lot better over the last few decades, but you only have to go online and see how people are judging others and judging themselves for not having had sex.

What is the biggest problem with sex education these days and what should be done to make it better?

There are incredible teachers and educators out there, and they all have the same refrain: They don't have the resources or the time. For Vice World News, I uncovered that the government failed to invest half of the amount they had promised into training teachers to deliver the new sex education program in England. That money is desperately needed. When I speak to teachers who really want more education, they're very vocal about wanting more information around online harms because, I'd imagine, they didn't go through these when they were young themselves and need the education about it to feel confident.

Secondly, as adults, loads of us had bad sex ed. And now we're no longer in educational settings. How do you reach us with good information about sex? And that's where you need social media platforms, newsrooms and television commissioners to realize there is a misinformation crisis happening about sex, our bodies and our relationships. We need to solve this as a society to be better at commissioning content that will reach all age groups.