Suicide Risk Factors and Warning Signs

Editor's note: This first of two related stories features information and discourse on suicide. Please use discretion with regard to reading and sharing the story. Anyone showing warning signs for suicide or observing those signs in another person can call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 24/7 at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) or access the Lifeline Chat to connect with a crisis counselor online, 24/7.

Paul Baltimore, Ph.D., could be quite creative, according to his mother, Patricia. The American history professor at the Los Rios Community College District in California wrote a series of comics, composed short stories, recorded YouTube videos for his classes, entertained audiences with widely revered karaoke performances and made progress on a book about the history of botany.

"He was a very well-rounded and very well-loved person," Pat Baltimore said of her son, who took his own life on April 8, 2021, four days before his 50th birthday. It's exceedingly difficult to explain the experience of having that happen to someone so close, she explained. "The loss is immeasurable."

Baltimore, who moved from Pennsylvania to California to reconnect with her son, watched his mental health deteriorate. A month and a half before Paul died, she felt like she was grasping at straws, and by that point, it was too late, she said. However, now she wants to tell her son's story to help others.

Suicide awareness

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 45,979 people in the United States, a country with a population of about 330 million, intentionally ended their lives in 2020.

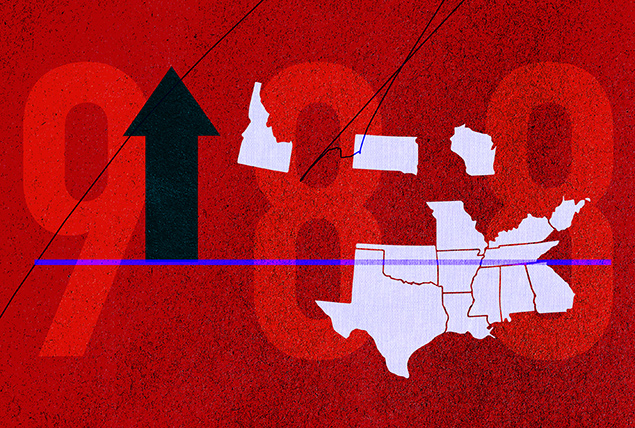

"Between 2000 and 2019, most WHO [World Health Organization] regions demonstrated a decline in the suicide rate, which was typically much higher than in the Americas throughout most years," said Stephen O'Connor, Ph.D., chief of the Suicide Prevention Research Program in the National Institute of Mental Health Division of Services and Intervention Research in Bethesda, Maryland. "However, the Americas was the only WHO region to demonstrate a rising suicide rate during this period of time."

About 1.2 million people in the U.S. attempted suicide in 2020, and suicide was among the top nine causes of death for people ages 10 through 64 that year, according to the CDC. It was the second-leading cause of death for people ages 10 through 14 and 25 through 34, too.

Rates of suicide, referring to the injury inflicted with the intention of ending one's life that results in death, are higher in the U.S. than in most other high-income countries, O'Connor added. The age-adjusted suicide rate in the U.S. went from 10.5 per 100,000 people in 1998 to 14.2 per 100,000 people in 2018, O'Connor said, basing the numbers on CDC data. Notably, though, the rate dropped to 13.5 per 100,000 in 2020, following a decline the previous year, as well.

Rates of suicide are higher in the U.S. than in most other high-income countries.

O'Connor suggested the recent trends might signal an end to "the gradual but consistent" increase in the suicide rate observed since the turn of the millennium. Data for suicide since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, which could either affirm or alter that picture, is not yet available.

Worldwide and in the United States, males account for a larger share of suicides, O'Connor added, with suicide by firearm being more common in the U.S. Veterans, residents of rural areas, LGBTQIA+ individuals and people with disabilities all have higher rates of suicide than the general U.S. population, according to information from the CDC.

Research suggests males are more likely than females to develop suicidality during marital separation and that the risk of suicide is four times higher for males than females following a separation. Recent research reaffirms that someone who has never been married is at increased suicide risk—which may be especially true if the person is in a low-income bracket—and separated individuals are more likely than married people to die by suicide.

Risk factors

Among young people in the U.S. between 10 and 24 years of age, the suicide rate increased 57 percent between 2007 and 2018, O'Connor noted. Pressure to embody perfection, possibly exacerbated by comparisons to peers who share polished photos on social media, may contribute to disconcerting trends. Experts point to an uptick in youth suicide since the launch of platforms such as Instagram which are fraught with images that could engender unrealistic expectations, especially among already overwhelmed adolescents.

Notably, though, all ages are affected by suicide, as CDC reports underscore.

Suicide is not a common response to adversity or mental illness. What has been termed "deaths of despair," which include suicides and deaths due to overdose, have been on the rise for 50 years, suggesting that further attention should be paid to risk factors, including ones often neglected in discourse about suicide awareness and prevention.

The CDC highlights higher suicide rates among workers in specific occupations, such as mining and construction, and lists a lack of employment security, suboptimal wages and work-related stress as factors that have been shown to contribute to increased suicide risk. These factors are also prevalent, perhaps surprisingly, in fields such as higher education, as the late professor Baltimore's experience attests.

Pat Baltimore said she believes work-related issues had the biggest effect on her son's deteriorating mental health. Despite earning a doctorate from the University of California, Santa Barbara, he could barely manage to pay rent or afford to keep his refrigerator stocked with healthy food while working as a part-time professor, cobbling together whatever classes he could to attain even a minimal standard of living in the Sacramento area.

He initially kept these issues from his mother, who for a time was largely unaware of higher education's two-tier system, which relegates many educators to contingent, frequently part-time faculty positions with little or no benefits and paltry pay. Burdened by massive debt and stuck on the bottom tier of that employment structure, Paul Baltimore, according to his mother, felt like a failure because he had such great aspirations in the teaching profession.

"He came alive in a classroom," she said. "And he was like, 'I've gone through all this. I have massive student debt. I've put my all into this career that I wanted. And I'm going to be 50, and I have nothing to show for it.'"

A 2013 meta-analysis of relevant literature found a statistically significant relationship between indebtedness and mental disorder, depression, and attempted and completed suicide.

"At the individual level of analysis, summarizing recent research in areas affecting risk of deaths by suicide, perhaps one of the most consistent predictors of suicide is low income," Steven Stack, Ph.D., a professor of criminal justice at Wayne State University in Detroit, wrote in a 2021 review for Preventive Medicine.

A 2018 meta-analysis and systematic review examining 22 studies identified "adverse psychosocial working conditions" as potentially contributing to suicidal thoughts and actions. These include "low job control," referring to a lack of work-related decision-making power and limited work opportunities to develop new skills at work; high job demands, referring to excessive workload and job pressures; imbalances in effort exerted at work and reward received for that labor; as well as concerns about job security.

All those psychosocial exposures increased the risk of suicidal ideation, the authors of the review found. Low job control is a condition arguably affecting a majority of people denied a substantive say over decisions affecting them within typical workplace arrangements. Low job control predicts and increases the risk of death by suicide, as an Australian national population-level study published in 2017 found to be the case for males, after adjusting for socioeconomic status, and authors of a 2007 community-based cohort study previously concluded with respect to male workers in Japan.

Warning signs

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) recommends the use of evidence-based screening, assessment and treatment strategies to help reduce the risk of suicide across a person's life span. Additionally, improvements in quality of care, continuity of care and the training of providers in suicide prevention core competencies all represent important components of health systems that are effective at addressing suicide risk among service users.

Mark Mayfield, Ph.D., is a licensed professional counselor and author of "HELP! My Teen Is Self-Injuring: A Crisis Manual for Parents," which features the author's own suicide survival story. He said risk factors for suicide can include not being (or feeling) seen, known, valued or loved. Still, warning signs are not always overt.

"I think some of the signs are…categorically withdrawing from things that are important," Mayfield noted.

Mood swings, looking for lethal methods online, demonstrable feelings of extreme guilt or shame, increased drug use, acting agitated or anxious, expressions of rage and the desire for revenge are other warning signs someone may be at risk for attempting suicide, O'Connor confirmed.

Additional warning signs someone might be suicidal, according to the NIMH, include expressing a desire to die, feeling hopeless, feeling trapped, believing there aren't any solutions to life's problems, talking about being a burden on others, saying goodbyes, giving away prized possessions, and experiencing severe emotional or physical pain.

The Didi Hirsch Suicide Prevention Center in Los Angeles also has a list of both warning signs and risk factors, as well as ways to help.

Anyone showing warning signs for suicide or observing those signs in another person can call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 24/7 at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) or access the Lifeline Chat to connect with a crisis counselor online, 24/7.