How Your Dog Knows When You're Not Well

Kim Denton, who has had type 1 diabetes for about 50 years, said she might not sense severe low blood sugar, or hypoglycemia, until her blood sugar drops below 40 milligrams per deciliter—maybe not even until it gets to 25 milligrams per deciliter, the point at which a person often passes out.

Denton recalled being home alone one day with Troy, the golden retriever she had just taken home from Dogs4Diabetics (D4D), a program affiliated with the National Institute of Canine Service and Training, and a provider of training and service dogs for people with diabetes who are insulin-dependent. Troy wandered over and alerted her to check her blood sugar. Plastering himself in her lap and refusing to leave, Troy would not let her get up.

"He sat on my lap the entire time till my blood sugar went back up to a normal amount," said Denton, who now works as the finance director for D4D. "And I would have been dead if I had not had him tell me that because nobody would have been around."

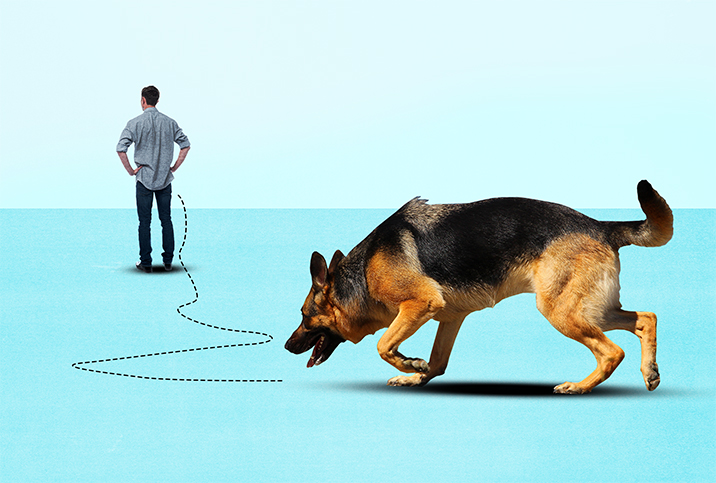

Troy's heroics are all in a day's work for dogs like him that sniff out potential problems in humans. The power of the canine sense of smell to detect disease and fluctuations in physiological markers in humans has proved effective in controlled experiments and, more importantly for Denton and others like her, in practice.

The research into dog sniffing

Medical Detection Dogs, a charitable organization based in the United Kingdom, trains Bio Detection Dogs to sniff out disease odor in urine, breath and sweat samples. The organization's founder, Claire Guest, co-authored the first published study of canine bladder detection, which showed dogs can be trained to distinguish urine samples of people with bladder cancer from those without, simply based on odor.

Medical Detection Dogs recently assisted Milton Keynes University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust with a clinical trial to study canine detection of prostate cancer, and the Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust to discover how well dogs can detect colorectal cancer from urine. The organization has also collaborated with Manchester University and Edinburgh University to study the ability of dogs to detect Parkinson's disease, possibly years prior to any symptoms. Another task was to have their dogs examine pieces of socks of 400 schoolchildren in The Gambia, West Africa, to determine which were worn by kids who had contracted a parasite that causes malaria.

The power of the canine sense of smell to detect disease and fluctuations in physiological markers in humans has proved effective in controlled experiments.

Echoing similar research on dogs detecting prostate cancer, Guest collaborated with researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) on a study in 2021 that tested the feasibility of early prostate cancer biosensing through an artificial neural network based on data from trained dogs' olfaction diagnosis. Researchers aimed to pave the way toward the development of machine-based olfactory diagnostic tools that define and recapitulate what can be detected and accomplished via canine olfaction, as the authors concluded.

Guest and colleagues are busy working with dogs to detect COVID-19.

Jennifer Essler, Ph.D., formerly a postdoctoral fellow with the Penn Vet Working Dog Center in Philadelphia, co-authored a study published in April 2021 in which dogs were able to discriminate between the urine samples of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID. Essler's research includes exploring biomarkers that might be useful in screening detection dogs, and using dogs trained to find ovarian cancer from blood plasma to identify compounds canines use to make their determinations in hopes of creating an "electronic nose" early-detection system for ovarian cancer.

The Penn center has also researched canine detection of cancer, COVID-19, biofilm infections and sinonasal papilloma.

What diabetic alert dogs do

In the U.K., dog instructors who leave or retire from the Metropolitan Police sometimes move on to training dogs to help kids. They might end up working with Hypo Hounds, a charity that trains diabetic alert assistance dogs. According to founder Jane Pearman, dogs at Hypo Hounds are trained via food rewards and play to recognize subtle changes in a child's blood sugar levels before they become a problem.

"We take samples of the child's breath in different ranges, and then from as young as 12 weeks, the dogs are taught to recognize that smell as being 'abnormal,'" Pearman explained, adding that successful smelling and alerting results in the dog getting a treat. "To the dogs, it is a huge game with a high-value reward at the end and they just love playing it."

D4D was founded by Mark Ruefenacht, whose life was saved by a dog who woke him up in the night after he had experienced a seizure provoked by plummeting blood glucose levels. Carrie Treggett, a program manager with D4D based in the San Francisco Bay area, said Ruefenacht worked with a pharmaceutical company to identify key chemical compounds emitted by the liver that dogs seem to smell. The thinking goes, as the liver tries to counteract major blood sugar changes, it releases compounds dogs can detect in our breath and perspiration.

Treggett said her organization typically trains dogs for three months to two years, depending on whether they get the animals as puppies and on any prior training they've had. With instruction catered to each canine's personality, they teach the dogs to bark, whine, gently nudge or pick up a brinsel—an item hanging from a collar that a dog can pick up in the mouth—to alert an owner.

"Having low blood sugar is life-threatening to a client," Treggett said. "To the dog, it means, 'I get some yummy treats,' and so they're super-motivated and so they get super-excited."

The thinking goes, as the liver tries to counteract major blood sugar changes, it releases compounds dogs can detect in our breath and perspiration.

D4D often trains 10 to 12 dogs at a time, and the program has 27 hypoglycemia-sniffing sleuths at present. These canine companions can augment the power of existing technology to detect blood sugar changes, and serve as a fail-safe when equipment inevitably fails.

Denton's continuous glucose monitor tells her insulin pump to reduce insulin if her sugar starts dropping or increase it if her sugar starts rising, but she said her dog Troy often outperforms all the technology.

"He's been 15 minutes ahead of my continuous glucose monitor," Denton explained.

Treggett said dogs might alert a client when the person's blood sugar is around 167 milligrams per deciliter, in which case they're supposed to wait 10 minutes and test again to see if the blood glucose drops more than 10 percent, which would indicate the dog's early alert was accurate.

"So we find that people go from 167 milligrams per deciliter to 92 milligrams per deciliter in 10 minutes, and so that's a huge drop in their blood sugar that the dog is picking up on," she said, noting that D4D training requires a dog to obtain 90 percent accuracy before being placed with a client.

Beyond beating glucose monitors to the draw, dogs also offer emotional support, Treggett noted. Regularly interacting with friendly labs and retrievers is often more motivating and enjoyable than merely receiving an alert from a lifeless screen or a reminder from a parent or spouse to check blood glucose.

Alert dogs save—and enhance—lives

Treggett said dogs are typically within 4 to 5 feet of the client when performing their detection duties, although she's aware of many cases in which this proximity was not necessary. According to Pearman, a Hypo Hound assigned to a client once alerted from home while the child was at school several miles away.

"The parent rang our office stating that the dog was acting really strange and was continually alerting even though the child was not in the house," Pearman explained. "We told her to log the alert and see what the child's monitor said when she got home. But she didn't have to wait. The school rang stating that the little girl was having a very bad hypo at school and they were struggling to get her bloods up."

Adolescents and young adults going off to college also benefit from medical detection dogs, Treggett said. The dogs enable independence otherwise impeded by the need for a parent to check their child's blood sugar in the middle of the night to prevent a sudden, silent tragedy.

Trained alert dogs, which possess a sense of smell so powerful they're purportedly able to detect one part per trillion concentrations of substances—tantamount to sniffing a single drop of liquid in the equivalent of 20 Olympic-size swimming pools—also offer adults with diabetes the comfort of another living, caring creature and greater independence.

Before she got Troy, Denton wouldn't leave in her vehicle for more than half an hour in case her sugar crashed without warning and she caused an accident.

"Now Troy alerts, and he does it way in advance [of] when I have a problem so I can treat it," Denton said. "You know, just pull over, check my sugar, treat it and we're on our way. And so I go places now. It's amazing."