Study: Trained Dogs Beat Electronic Nose at Detecting Prostate Cancer

Have you ever scolded your dog for stopping during a walk to sniff every hydrant, tree trunk and other dog? Maybe you should stifle your censuring, because it's possible your canine is practicing for a lifesaving mission (never mind the feces on its snout).

With more than 200 million olfactory cells in their noses, dogs have sniffers that are about 100,000 times more sensitive than ours, according to the American Kennel Club (though this number varies widely by source). These powerful detection devices have been used to sniff out bombs, drugs, epileptic seizures, corpses, the beef jerky cleverly hidden in the pantry and more.

Now, a team of Italian researchers has shown that not only can dogs detect prostate cancer in urine samples, but they can also do it better than the best available technology.

The competition

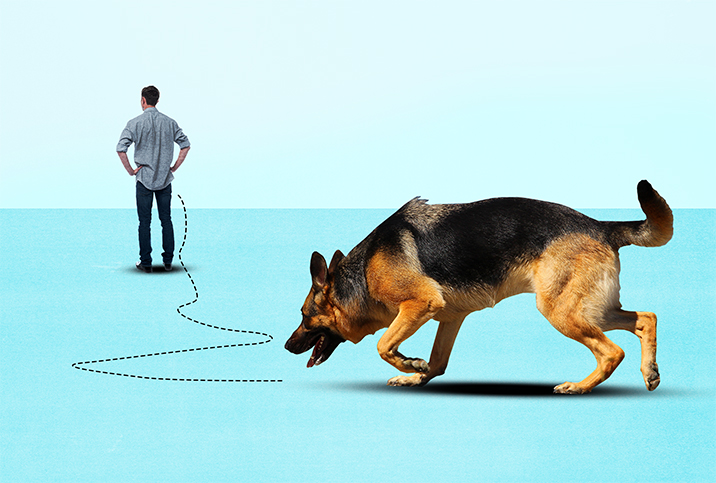

In a very John Henry-esque tale, researchers pitted two specially trained German shepherds against an electronic nose (e-nose), a device that detects odors and flavors, and has been in development for a while but is still a young technology. The competitors' mission: correctly discern which of 174 urine samples came from men with prostate cancer.

As explained during a virtual press conference at the American Urological Association's 2021 annual conference in Las Vegas, 88 samples comprised the prostate cancer group and 86 samples comprised the control group. To complicate matters for the competing noses, the control group included women and people with cancers other than prostate. No one in the control group had prostate cancer.

So what exactly were the dogs and e-nose looking for in all that human urine? Researchers are pretty certain those super-sensitive snouts can detect VOCs—volatile organic compounds created by cancer-cell metabolism—which give off a specific odor. In fact, the odor is so specific, each cancer has its own scent.

The results? In a nutshell, the two dogs achieved 97.7 percent and 96.6 percent accuracy for sensitivity (detecting the presence of cancer), and 98.8 percent each for specificity (identifying prostate cancer as the cancer present), according to Gian Luigi Taverna, head of urology at Humanitas Mater Domini in Italy. The e-nose succeeded at 85.2 percent and 79.1 percent for sensitivity and specificity, respectively, but did best with high-grade cancers.

Researchers hope they can get the e-nose to more closely mimic the dogs' olfactory system by improving the sensors.

"Most of the misclassified samples are the low-grade tumors," said professor Laura Capelli, of the Department of Chemical Engineering at the Politecnico di Milano University, during the virtual press conference.

While it may seem simple to say, "Hey, let's put trained dogs in hospitals all over the world"—seriously, how great would that be?—the use of canine cancer diagnosers has issues. During the virtual discussion, Taverna listed the following problems:

- Each center needs to be highly qualified.

- The training for both dogs and handlers is extensive.

- Dogs have a limited life span, leading to low sustainability and reproducibility on a large scale.

- Hospital protocols make it difficult to introduce dogs.

Thus, going forward, the researchers are attempting to make the e-nose even better at recognizing prostate cancer in urine samples.

The goal is better technology

In the end, this study isn't about mammal versus machine. It's about improving human-designed detection, which will eliminate many unnecessary prostate biopsies. Taverna said researchers hope they can get the e-nose to more closely mimic the dogs' olfactory system by improving the sensors. One way to accomplish this is through sheer volume: The more samples they get, the more the e-nose can "learn" and improve, Capelli said.

"We are very happy with the results we have obtained and we are very happy because we have seen them improving over the years," Capelli said, adding that researchers believe 90 percent accuracy is well within their capabilities, but a lot more testing and research are needed.

"It's clear that dogs are still the best," Taverna said, adding that reaching the same accuracy level as the dogs is the dream but may not be feasible. While dogs possess hundreds of millions of olfactory receptors, the e-nose, necessarily, has a limited number of receptors.

Even so, the researchers have big goals for the use of the nose.

"[Its use will] come right after the PSA analysis," Capelli said, referring to prostate-specific antigen tests. "It's a screening instrument that gives the clinician or urologist information on which patients should further undergo an MRI and a biopsy. So we see it being used somewhere between PSA and biopsy."

If this experiment yields results that improve electronic-nose technology and benefit men in the long run, perhaps we should let more things go to the dogs.