Surgery May Lengthen Survival for Some Ovarian Cancer Patients

For many years, ovarian cancer was known as the "silent killer," often undiagnosed until after the disease had progressed to an advanced stage. Symptoms went undetected or were confused for menstrual or gastrointestinal issues. And it's all too common for ovarian cancer to come back after the patient has undergone treatment, particularly in more advanced stages.

"For most patients with advanced-stage ovarian cancer, recurrences are, unfortunately, part of the natural history of the disease," said Shobhana Talukdar, M.D., a gynecologic oncologist at Arizona Oncology. "In more than 7 of 10 people with ovarian cancer, the cancer can recur after initial treatment."

But a 2021 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine offers a bit of bright news for patients with recurrent ovarian cancer. Known as the Desktop III trial, the study randomized 407 women with recurrent ovarian cancer into two groups. One group received cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and chemotherapy, and the second group received chemo alone. Those in the CRS and chemotherapy group had longer periods of survival. The median survival time was 53.7 months (and up to 61.9 months), compared with a median survival time of 46 months in the chemo-only group.

What is cytoreductive surgery?

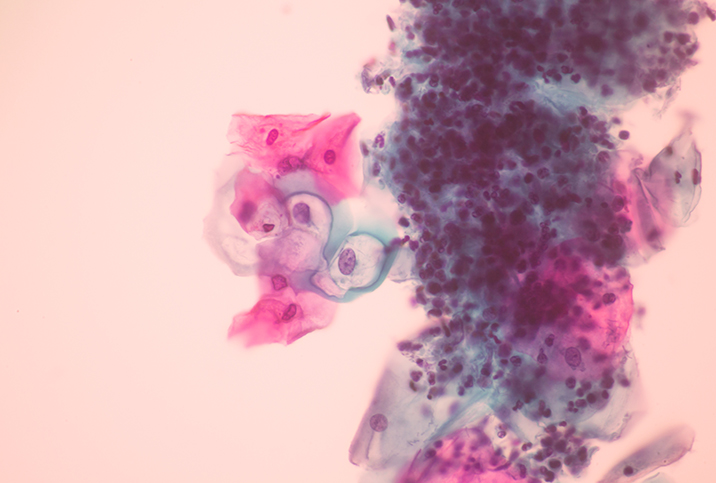

Cytoreductive surgery, also known as debulking surgery, is a procedure in which all visible cancer is removed from the abdomen and pelvic region. An initial CRS also typically includes the removal of both fallopian tubes and ovaries, as well as the uterus, cervix and omentum.

Most patients undergo CRS after their initial diagnosis, either before or during chemotherapy. The surgery is usually performed through a large abdominal incision so the surgeon can explore the area for more cancer, but it may also be done in a minimally invasive method using laparoscopic or robotic surgery.

"Among various gynecologic cancers, this surgery is commonly performed in advanced-stage ovarian and endometrial cancers," Talukdar said. "This is a type of radical surgery where the surgeon works to remove as much visible cancer around the ovaries and throughout the abdomen as possible, especially tumors larger than 1 centimeter. The more cancer that's removed during CRS, the better the outcome."

There are clear benefits to the surgery.

"For women with ovarian cancer, removing all visible tumors at the time of initial CRS has been shown to improve survival," said Michelle Lightfoot, M.D., a gynecologic oncologist at NYU Langone's Perlmutter Cancer Center in New York City. "Recurrent ovarian cancer is typically treated with systemic therapy, without surgery."

But as with other types of surgery, CRS is not without recovery downtime—and risks. The hospital stay and recovery time are longer for patients who've had the open surgery with the abdominal incision. Any surgery bears the risk of postoperative complications, including pain, blood clots, infection, intestinal blockage and more. Women who are perimenopausal and have both of their ovaries removed during the surgery will start menopause early and also be unable to bear children, Talukdar added.

"Patients need to discuss these issues with their doctor before surgery," Talukdar said. "It's essential the patient is fully informed of the procedure and its potential benefits and risks. This type of procedure should be performed by a gynecologic oncologist who specializes in cancers of the female reproductive system."

It's not an option for every patient

"Desktop III was very important because it was the first prospective randomized trial to show an overall survival benefit with debulking surgery in recurrent ovarian cancer," Talukdar said.

The trial found an additional round of CRS after patients' ovarian cancer had returned, paired with chemotherapy, extended their survival. But these benefits don't necessarily extend to every woman with recurrent ovarian cancer.

"It is important to understand the inclusion criteria for the study, as most women with recurrent ovarian cancer may not be eligible for secondary CRS," Lightfoot said.

To participate in the study, women had to have a certain type of ovarian cancer, along with other criteria. Participants had to have epithelial ovarian cancer that was platinum-sensitive, Lightfoot said, meaning their cancer recurred six or more months after they finished their first platinum-based chemotherapy.

In addition, Talukdar said trial participants had to meet three other criteria:

- Their initial CRS had to have removed all traces of visible disease.

- They had to be able to carry out daily activities without any restrictions.

- They had to have little or no buildup of fluid in the abdomen, which can indicate cancer has spread more widely.

"Many individuals with recurrent ovarian cancer will not meet these criteria, and the benefit of secondary CRS should not be extrapolated to individuals who would not have met study eligibility," Lightfoot said.

Additionally, this study was conducted before PARP inhibitor maintenance—which blocks cancer cells from repairing their DNA damaged by chemotherapy—became a routine form of care. PARP, or poly-ADP ribose polymerase, is a protein (enzyme) found in cells.

"Many patients now receive PARP inhibitor maintenance therapy following primary chemotherapy," Lightfoot said.

What is the biggest takeaway from this research?

"There is not a one-size-fits-all approach to treating recurrent ovarian cancer,” Talukdar said. "Surgery still plays an important part of treatment in a select group of patients with recurrent ovarian cancer. For individuals who meet strict criteria, surgery could or even should be considered, but only if a patient has access to an experienced and skilled surgeon."