How Cystic Fibrosis Affects Women's Sexual and Reproductive Health

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a systemic genetic condition that causes bodily secretions to become thick and sticky instead of thin and slippery. Although it primarily impacts the lungs and pancreas, cystic fibrosis affects several body parts and organs, including the reproductive system and overall sexual health.

A person can inherit cystic fibrosis if both parents pass on a mutation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene. The gene helps regulate the movement of chloride (salt) and water in and out of cells to ensure secretions—mucus and digestive juices foremost among them—are the proper consistency to provide lubrication.

When the gene is defective or missing, the water-to-salt ratio is off-kilter and causes these secretions to become viscous. As a result, mucus can accumulate and plug up affected areas, causing infections, inflammation and damage.

Cystic fibrosis is an incurable, lifelong illness that can substantially affect a person's health. Although complications such as malnutrition and lung disease are most prominent, CF can impair a person's sexual and reproductive well-being, contributing to issues such as urinary incontinence and diminished fertility.

"Sexual and reproductive health is important for all people, including those with chronic conditions such as cystic fibrosis," said Traci M. Kazmerski, M.D., an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh, in an email interview. "Sex, intimacy, and considering one's reproductive goals and future is part of the human experience and should be addressed with everyone."

Managing cystic fibrosis can be onerous for anyone, but there are challenges specific to women.

Cystic fibrosis and the menstrual cycle

In a survey of 460 women with cystic fibrosis ages 25 and older, Kazmerski and her colleagues found approximately 1 in 4 reported their symptoms worsened immediately before or during their period. The reason isn't clear, though hormone changes and inflammation likely contribute.

In some people, side effects of cystic fibrosis, including malnutrition and low body weight, may impact ovulation and contribute to irregular or missing periods (amenorrhea), according to the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF).

Increased risk of yeast infections

The antibiotics and corticosteroids used to treat cystic fibrosis can alter the vaginal acidity and microbiome. As a result, the bacteria Candida albicans may proliferate, leading to fungal vaginitis or a yeast infection.

Antibiotics kill both good and bad bacteria, which allows yeast to grow—sometimes out of control, Kazmerski explained. Yeast infections are most likely to occur during your period or when you start or change antibiotics, she added.

Kazmerski recommended women avoid vaginal douches—they can disrupt the vaginal pH and microbiome—and wear breathable underwear and loose-fitting pants. She also advised quickly changing out of wet bathing suits or sweaty workout clothes as yeast tends to flourish in moist environments.

Some people find consuming probiotics, either in foods such as yogurt, kefir, kimchi or sauerkraut, or in pill form, can help stave off infections, too.

"However, doing these things alone may not prevent and cannot cure an existing yeast infection," Kazmerski said. "People with cystic fibrosis should talk with their team if they experience frequent yeast infections and may be prescribed an antifungal medication.

"Importantly, if people with cystic fibrosis are taking a CFTR modulator medication, they will need dosing adjustments to that therapy when on certain antifungals," she added.

Urinary incontinence

Urinary incontinence, or leaking urine, is common in people with cystic fibrosis, particularly women, according to Kazmerski and Michael Green, M.D., an OB-GYN and the chief medical officer at Winona, an online wellness center for women.

Usually, this symptom develops because frequent coughing weakens the pelvic floor muscles.

"Pelvic floor physical therapy may be especially beneficial in treating this symptom," Kazmerski said. "Additionally, your cystic fibrosis team may refer you to a specialist, such as a urogynecologist, who may recommend other management strategies."

Inflammation and structural abnormalities, such as blockages in the urinary tract, can make it difficult for the bladder to empty, which may exacerbate incontinence, Green noted. Cystic fibrosis-related constipation can also put pressure on the bladder, increasing the urge to urinate, he said.

Medications such as antibiotics and bronchodilators can affect the bladder and contribute to incontinence, according to Green.

Pregnancy complications

Pregnancy isn't inherently dangerous for most people with cystic fibrosis, according to Kazmerski and James Miller, M.D., who practices at Monarch OBGYN in Wooster, Ohio. But it can exacerbate symptoms, including pulmonary issues. Rarely, severe complications can occur.

People with CF, especially those with low baseline lung function, are more likely to require a ventilator, develop pneumonia or acute renal failure, or die than pregnant people without the disease, according to Kazmerski.

Women with cystic fibrosis are more likely to have preterm or low-birth-weight infants, Kazmerski added. Medication changes may be necessary to reduce the risk of complications.

Fertility issues

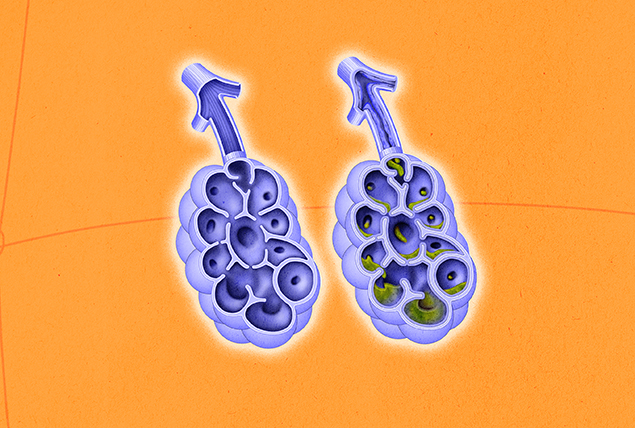

Some women with cystic fibrosis may have difficulty conceiving, primarily because cystic fibrosis can impede ovulation and thicken the cervical mucus, making it more difficult for sperm to reach the egg, according to the three physicians.

Inflammation in the reproductive tract may further inhibit fertility, Green said.

CFTR modulator therapies can mitigate these issues and potentially restore fertility for anyone struggling, Miller and Kazmerski explained.

Kazmerski emphasized that for people with cystic fibrosis who don't want to become pregnant, using contraception is essential whether or not they're taking CFTR modulators. Despite irregular ovulation and thicker cervical mucus, it is still very possible for otherwise healthy women with cystic fibrosis to become pregnant.

About 85 percent of people with the condition can conceive within 12 months of stopping contraception, according to the CFF.

Contraception concerns

All forms of contraception are safe for most people with cystic fibrosis, though there are some important considerations, Kazmerski said.

For one, hormonal contraceptives such as the patch and pill may be less effective in women with CF. That's primarily because certain related treatments, such as lumacaftor/ivacaftor, can inhibit hormone absorption and reduce the medications' effectiveness, according to Green and the CFF.

With the pill, decreased nutrient absorption in the small intestines of people with cystic fibrosis might also affect its efficacy, according to the CFF.

"They should also be aware that hormonal birth control methods can affect the absorption of antibiotics and other medications used to treat cystic fibrosis," Green said.

Women with cystic fibrosis who wish to use the pill may want to consider taking enzymes to facilitate better absorption and improve medications' efficacy, according to the CFF.

Furthermore, the CFF states that some hormonal contraceptives containing progestin may increase salt and fluid retention, while estrogen-containing products may increase the risk of blood clots.

Green advised avoiding diaphragms and cervical caps as well, as these can trap bacteria and increase the risk of infection. The CFF notes that thickened cervical mucus may make it difficult for these devices to stay in place, rendering them less effective.

For all of these reasons, Kazmerski stressed how essential it is to talk with your healthcare provider if you have CF to find the appropriate contraceptive option for your needs.