Diagnosing Cystic Fibrosis and Finding Care

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a lifelong genetic affliction with devastating effects on the body's systems. Since the discovery of CF, researchers have identified the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein as the source—more specifically, a mutation in that protein.

Cystic fibrosis is a genetic disease, meaning it occurs in a child whose parents are both carriers of the CFTR protein mutation. If only one parent has it, the child will not be affected.

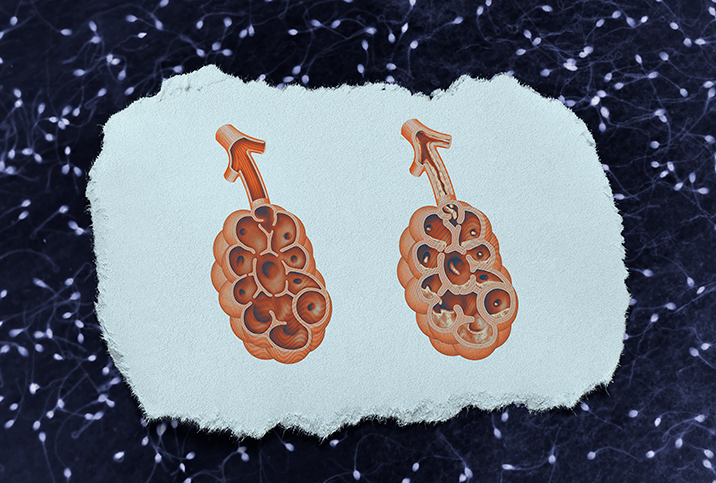

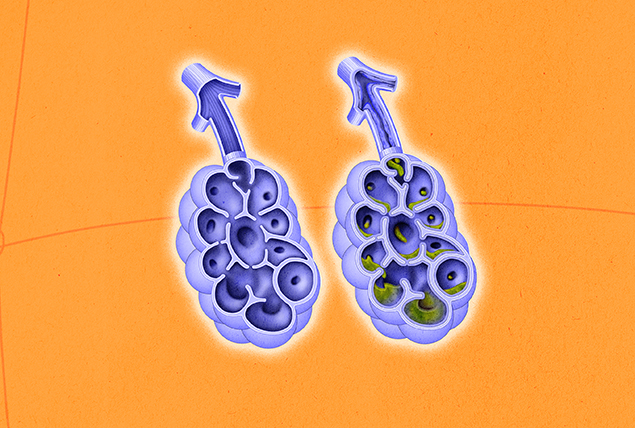

When there is an error in the CFTR gene that produces the CFTR protein responsible for salt and water transport on a cellular level, this leads to malfunction in many organ systems that depend on this balance and regulation of salt and water.

One consequence is the overproduction of more concentrated, gooey mucus that the body and its systems cannot easily remove, leading to detrimental blockages. This mucus can build up in airways (pulmonary system) or prevent adequate transport of important enzymes in the ducts and glands (GI tract) where mucus can build up, leading to difficulty with breathing and absorption of nutrients, respectively.

Intimacy and sexual function also can be affected, making treatment of significant importance.

Most patients take medication and supplements and use respiratory treatments indefinitely, and those who want to endeavor to start a family may need reproductive assistance. CF treatments may pose their own risks regarding immunity and comorbidity as well.

Common symptoms of cystic fibrosis

Signs of cystic fibrosis often present in myriad areas of the body and may begin as early as birth. Some people may be asymptomatic until their adult years and have less severe cases.

From a young age, CF sufferers may experience abnormally salty-tasting sweat and/or skin, and gastrointestinal issues, such as constipation and greasy stools.

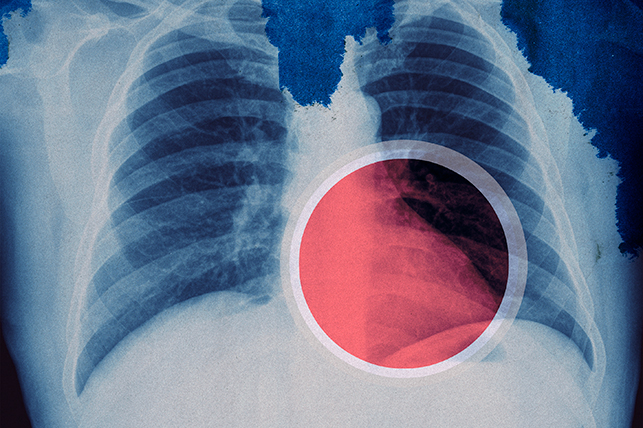

"People with CF often get lung infections and subsequent lung damage," said Traci M. Kazmerski, M.D., an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh. "In the gastrointestinal tract, the release of digestive enzymes is impaired, which can lead to poor nutrition and weight gain."

Though cystic fibrosis symptoms can include any combination of the aforementioned ailments, the most common are respiratory issues, such as coughing and wheezing with mucus, and sinus problems, such as nasal polyps. Later in life, people with CF often develop pancreatitis and osteoporosis. According to Kazmerski, most men experience infertility.

Diagnosis and testing

At the prenatal stage, parents can be tested for the CF carrier gene, CFTR. If one parent is a carrier and the other isn't, cystic fibrosis will not affect the child. If both parents are carriers, it is likely their child will have CF.

Prenatal testing procedures include amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling (CVS), where samples of fetal fluids or cells are taken to detect the CFTR gene mutation. There are alternate diagnostic tests for cystic fibrosis, two of which are performed at birth.

"The illness is diagnosed through a blood test for newborns. A child can undergo a chloride sweat test if the bloodwork returns positive for CF," said Jyoti Matta, M.D., a pulmonologist affiliated with RWJBarnabas Health in Jersey City, New Jersey.

The bloodwork tests for a marker pancreatic enzyme common in CF called immunoreactive trypsinogen (IRT).

"People with CF have a high level of chloride in their sweat," Matta explained. "Doctors can also do genetic testing if the test reveals a high chloride content."

These sweat tests are the gold standard for cystic fibrosis diagnosis after birth, according to Kazmerski. Two electrodes are put on the skin. One of them induces sweat by passing an electrical current through the skin, and this sweat sample is collected for testing. If chloride levels are 60 millimoles per liter (mmol/L) or higher, the person is diagnosed with CF.

The procedure takes less than an hour and the results are shared within a day or two. If the test results are positive, the patient will need to visit an accredited cystic fibrosis care center for additional tests to determine the mutation type and symptom severity.

When to seek help and who to see

If a family has a history of CF, prospective parents may want to be screened by a healthcare provider, such as a primary care doctor or OB-GYN, before they attempt to conceive.

From there, CF carriers can seek genetic counseling from a specially trained practitioner who usually has a master's degree and board certification. Anyone found to have cystic fibrosis needs to establish a multidisciplinary treatment team.

"Cystic fibrosis is a complex disease," Matta said. "A person with CF often needs support from medical doctors, physical therapists, counselors and other professionals."

The burden of the disease can be significant, and mental health is often compromised. Patients may need to include a psychiatrist or psychologist on their care team. Kazmerski and Matta recommended reputable cystic fibrosis care centers to tackle the turmoil associated with the disease.

The need for other professionals depends on symptom severity. Many people with CF experience malnutrition, so a dietitian or nutritionist may be enlisted to determine which vitamins, supplements and/or pancreatic enzymes are needed for proper nutrient absorption.

Cystic fibrosis tends to get progressively worse over time, and additional healthcare providers may be necessary to manage respiratory symptoms, reproductive issues, bone degeneration or further gastrointestinal complications.

What happens if it goes undiagnosed?

The diagnosis could be missed at the prenatal or postnatal stages if symptoms are not prominent or there is no known family history. Such is often the case with class IV, V and VI CFTR mutations, which may present few or no symptoms until adulthood. (Class I, II and III mutations are more acute and severe.)

Alternatively, some symptomatology may present but is misdiagnosed because it is attributed to other causes. Pancreatitis and nutrient malabsorption, for example, have numerous potential origins unrelated to CF. If few other symptoms are present, a patient may remain undiagnosed.

Overlooking a cystic fibrosis diagnosis is detrimental to a person's health. If mutations continue unchecked, they can cause irreversible damage to the respiratory (particularly the lungs) and gastrointestinal systems, including multiple organ failure. Organ transplants are hard to secure, and it is not uncommon for people with CF to die from these or other complications, especially if the condition isn't detected.

Myths and misconceptions

Cystic fibrosis is not unique in its ability to generate false speculation. Any medical condition is susceptible to misunderstanding. Though scientists and people directly impacted by CF now know much more about the disease, other populations may remain in the dark because they only know what they see, giving them the wrong impressions about what it means to live with CF.

One misbelief many people hold about CF is that it is only a disease of the lungs. For some people, seeing CF patients' frequent mucus-laden coughing and respiratory equipment may be the only outward physical evidence they know, so they may be unaware of the other areas impacted by cystic fibrosis. Malabsorption of nutrients and damage to the intestines and multiple organs occur conjointly. Plus, there is frequent incidence of reproductive dysfunction.

Other people believe CF is contagious, which couldn't be further from the truth. It is an inherited disease that cannot be acquired through any type of proximity, nor is it limited by demographics. Even though it is more common in white people, any race or ethnicity can get CF if it's passed on genetically.

Age isn't a factor, either, even though many people think cystic fibrosis is a childhood disease. In fact, more adults than ever are living with CF, largely due to medical advancements to help manage symptoms and reduce disease progression.

Despite everything it can cause, a cystic fibrosis diagnosis is not an immediate death sentence. If the complications are well-managed, patients can live quality lives well into adulthood, Matta said.