How Abortion Restrictions Affect Miscarriage Care

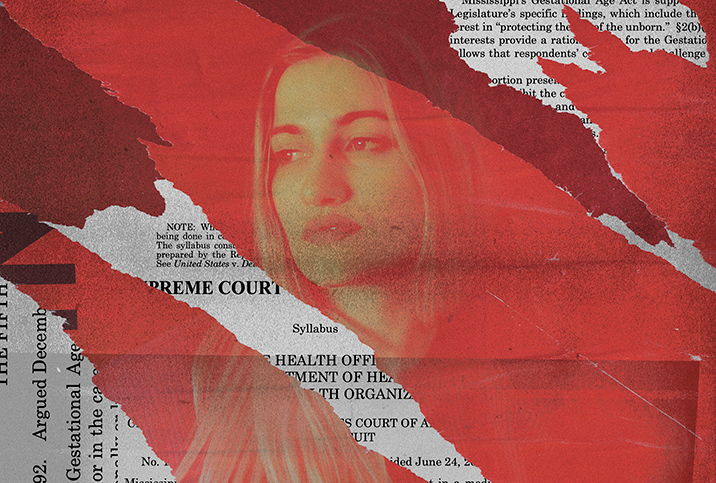

The Supreme Court's recent Dobbs decision launched a cataclysmic shift in reproductive rights across the country, with countless individuals, families and communities caught in the crossfire as states enacted new legislation or revived decades-old laws.

While many of the restrictions explicitly target people seeking, providing or abetting elective abortions, the language of some laws has been criticized by pro-choice activists as too vague. Activists have expressed concern that the language may cause confusion and uncertainty among patients, healthcare providers and the public.

As a result, some people who miscarry desired pregnancies cannot get the care they need.

Miscarriage vs. abortion

Part of the problem stems from the fact that miscarriages and elective abortions are, medically, essentially the same, as is their treatment.

A miscarriage, also known as an early pregnancy loss or spontaneous abortion, is a spontaneous loss of pregnancy before 20 weeks, according to the National Library of Medicine. Between 10 percent and 20 percent of pregnancies are thought to result in miscarriage, according to Mayo Clinic. However, that percentage may be higher as many miscarriages occur before a person realizes they are pregnant. A pregnancy loss after 20 weeks is referred to as a stillbirth.

"Medically, depending on the gestation of the pregnancy, management for abortion, as well as uterine evacuation after miscarriage, could be managed similarly. For early terminations or early miscarriage, medication can be prescribed to induce cramps and, ultimately, the expulsion of the pregnancy from the uterus," said Daniel Roshan, M.D., an OB-GYN at Rosh Maternal & Fetal Medicine in New York City.

"For miscarriages further along or terminations into the second trimester, surgical management such as a dilation and curettage [D&C] or maybe even a dilation and evacuation [D&E] is performed," he added.

The typical medications used for elective and spontaneous abortions are misoprostol or mifepristone, which soften and dilate the cervix and cause the uterus to contract, explained Julia Arnold VanRooyen, M.D., an OB-GYN in Wayland, Massachusetts.

With these medications, the process typically takes between a few hours and two days to expel the pregnancy. A D&C usually takes less than 30 minutes. A spontaneous miscarriage without treatment can take up to two weeks or longer.

Most women do not require medical intervention for an early pregnancy loss, but doctors might intervene if a patient wants to speed up the process or if it is necessary to address an incomplete miscarriage or other serious complications, some of which can be life-threatening.

What the laws say

Several supporters of the Dobbs decision, which overturned the court's 1973 ruling in Roe vs. Wade, and subsequent abortion bans have said hurdles for people with ectopic pregnancies, miscarriages and similar situations are a result of misinterpretations and missteps, not the new laws, and it's true the state-level bans do not explicitly forbid such care.

Nonetheless, the uncertainty surrounding what is and isn't permitted, and potentially life-altering consequences for those who get it wrong, have led some healthcare providers to withhold essential services for miscarriage treatment. In addition to certain hospitals refusing to administer the D&C or medications, some pharmacies have denied or delayed issuing prescriptions for misoprostol or mifepristone.

"It is affecting patients' physical health as well as their mental health," said Sarah Yamaguchi, M.D., a gynecologist at DTLA Gynecology in Los Angeles. "They can become sick due to delayed care, and it can go so far as to affect their ability to carry a pregnancy later."

The Biden administration has said that if a pharmacy refuses to fill prescriptions, including those classified as abortifacients needed to manage miscarriage or pregnancy loss complications, it may be treated as discrimination based on sex. Nonetheless, some providers remain apprehensive.

"Unfortunately, abortion restrictions do not define an elective termination from a medically indicated one," Yamaguchi said. "With restrictions taking place, they can interfere with women being treated for their pregnancy losses either due to laws directly restricting it or by hesitancy on the part of providers or hospitals to provide care and expose themselves to liability or bad press."

"Physicians across the country are stopping to consider whether any aspect of care they provide might be in violation of their state's web of abortion laws," VanRooyen added. "Laws allowing abortion to save the mother's life generally do not specify what that means. How sick does she have to be before her life is considered to be threatened? Moribund? Septic? Eclamptic and seizing or just preeclamptic with a little liver or kidney damage? Anemic from hemorrhaging to the point where she is at risk of cardiac arrest? Or renal failure?

"None of these things are specified in the law, yet doctors are grappling with these real-life variables daily," VanRooyen continued. "And it's not just obstetricians and gynecologists who must navigate these conditions. Emergency medicine doctors, anesthesiologists, oncologists and others must think about whether they might be 'abetting' a woman having an abortion if they participate in her care."

The dangers of delayed care

Pregnancy loss can cause a variety of symptoms. Sometimes, VanRooyen explained, the person is unaware of any changes until blood tests or an ultrasound show the pregnancy has ended.

"The most common symptoms of a miscarriage are vaginal spotting or bleeding, with or without pain. It is also possible to have a small gush of fluid from the vagina, even without bleeding. The symptoms may be similar to a heavy period, including the passage of blood clots or even fetal tissue, depending on how far along the pregnancy is," VanRooyen said, adding that mild cramping or bleeding early in pregnancy is normal and doesn't necessarily indicate a pregnancy loss.

But for some people, the pain of a miscarriage is intense or even debilitating. Hemorrhaging can occur, and infections and sepsis can develop if the pregnancy tissue is not completely expelled. According to Mayo Clinic, septic miscarriages—a medical emergency—cause the following symptoms:

- Fever and chills

- Lower abdominal tenderness

- Foul-smelling discharge

VanRooyen said if a person develops any of these symptoms or is bleeding heavily enough to soak two pads per hour for two consecutive hours, they should call a doctor immediately.

"Although approximately 80 percent of pregnancy losses occur before 13 weeks [first trimester], the remaining 20 percent occur after this point and require medical intervention," VanRooyen explained. "There is a greater risk of complication [hemorrhage, infection] after 13 weeks [second trimester] and a greater likelihood that surgical intervention will be necessary."

She added that medical abortion is a standard treatment for many pregnancy complications, from sepsis and preterm rupture of membranes to severe preeclampsia and intrauterine demise. Now, any situation in which abortion would typically be offered or recommended poses a significant challenge for providers.

"Pregnant people suffer in the meantime. They get sicker, more anemic and more seriously ill while doctors call lawyers or crisis management teams to try to ensure they are operating within the law," VanRooyen said. "Some of these women will lose their uteruses while they wait; lose their future fertility permanently. Some may suffer complications that will also affect their future fertility. Others will need transfusions, antibiotics, imaging studies or other interventions. Ultimately, some will die.

"It is simply impossible to create an all-inclusive list of conditions a pregnant person might encounter that would qualify as life-threatening emergencies," she continued. "It is also impossible to predict how any given patient with a specific condition will progress or how rapidly they might progress. These laws prohibit physicians from making individualized assessments and recommending the best course of treatment for each patient in her unique circumstances, and pregnant patients are suffering because of it."

How to cope

It's currently unknown if states with stringent restrictions will revise legislation to clearly differentiate between elective and spontaneous abortion. In the meantime, experts advise anyone who is pregnant or planning to become pregnant to discuss miscarriage management options with their doctor ahead of time.

"This issue should not be managed by a woman miscarrying," Yamaguchi said.

"Patients should always talk to their doctor about any concerns regarding their pregnancy," VanRooyen said. "Have this conversation ahead of time, if possible, and your doctor should be able to provide you with guidance for the specific hospital where you plan to receive your pregnancy care. Many hospitals have formed emergency committees or have individuals on call to address urgent pregnancy questions as needed."

Yamaguchi added that this topic should concern everyone, pregnant or not. Although speaking out might not make a significant political change, she said, "You have no idea how many people around you have to deal with a miscarriage, and hearing your support about the issue really will help."