We Have Questions: Nutrition, Dairy and Prostate Cancer

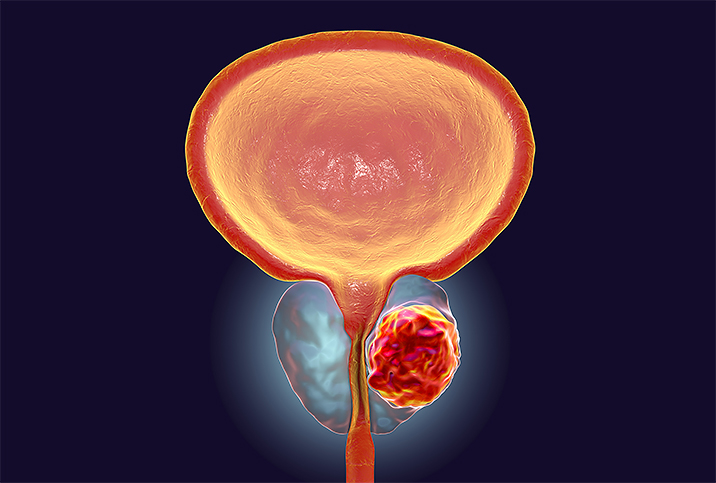

Risk factors for prostate cancer include age, race, geography and family history, among others. But researchers also know of a potential link between the disease and a common block of the food pyramid and are still working to figure it out.

Multiple recent studies have unearthed a possible connection between dairy and prostate cancer.

"Our data suggest a positive association between high-fat milk intake and prostate cancer progression among patients diagnosed with localized prostate cancer," stated one such study published in the International Journal of Cancer.

Another study, this one in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, concluded, "Men with higher intake of dairy foods, but not nondairy calcium, had a higher risk of prostate cancer compared with men having lower intakes."

But maybe wait before dumping all the milk and cheese in your fridge, because other findings are inconclusive at best. In an interview, Kristina Penniston, Ph.D., a senior scientist in the University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of Urology and a registered dietitian, explained the relationship between nutrition and cancer in general. She helped us understand exactly what it is about dairy that could (or could not) increase a person's risk of developing prostate cancer specifically.

Editor's note: The following interview was edited for length and clarity.

What role does diet play not only in prostate cancer but in all types of cancer?

Penniston: It's complex, as you might imagine. Nothing with the human body is simple. There's usually more than one cause or contributor to the development and the progression of cancer. In some cases, diet can play a large role in the onset, the development and the progression of the cancer. But in other cases, it may play a very minor role or even not a role at all. You can find examples of people who have what we might consider to be a very unhealthy or unbalanced diet and they live to 100. And then there are also people who have wonderful diets, very balanced, and they do everything so-called right and then they die at 50. So there's no justice, and we have not figured it out yet. All we know is that if we follow healthy diet principles from an early stage in life, we are less likely to form cancers, but there's no guarantee, certainly.

What are the challenges of studying nutrition's role in the development of cancer?

Nutrition is very difficult to study in terms of its effect on all diseases, and the reason is diets are complex. We don't just eat one nutrient at a time. We follow different diets throughout our lifetime. So when we look at studies that go back in time—which is what many of these large studies do that have found these findings regarding dairy—they get a group of people and they'll ask them to look back in their history and to estimate, for example, the number of times a week over the past year that they eat certain foods. I see people all the time who can't even remember what they ate yesterday, let alone a year ago.

Secondly, diets change even within a year. I might eat watermelon every day for three months but then never for nine months. And then the other problem with those kinds of data-gathering instruments are portion sizes; that's interpreted quite differently by people. And how do we know we're not picking up the influence of some other factor, for example, a lifestyle factor, a chemical exposure? It's very difficult to study diet in terms of health and disease.

How might dairy specifically play a role in the development of prostate cancer?

There is a lot of attention on dairy for a number of reasons recently. Back in the 1980s, when this whole low-fat sort of kick [began], everything became low fat and we started supplementing our foods with all kinds of carbohydrates and sugar. We now realize that not all fats are bad; it's really saturated fat we want to limit. So dairy, because it's very full of saturated fat, has kind of been implicated in diseases where saturated fat may play a role, and cancer is one of them. We think saturated fat causes inflammation and we think that inflammation can give rise to cell mutation, which is the initiating factor of cancer.

So dairy has gotten a lot of attention recently, and there have been some large epidemiologic studies which are fraught with those kinds of errors [and difficulties] that I talked about earlier that link dairy to prostate cancer. But there are also studies that say the opposite, that find no link between prostate cancer and dairy. No one's really proven yet what the mechanism is for dairy.

We know age can play a role in the development of prostate cancer. Could dairy intake at a certain age increase that risk as well?

Not necessarily about dairy, but we know there is an age effect with certain things. For example, with breast cancer, which is one of those hormone-sensitive cancers, there is data that shows adolescent girls have better protection against breast cancer if they have exposure to soy in their adolescent years. So what that tells me is this sort of thing must exist with other parts of our diet, so I'm not ruling anything out.

I will say, as men age, their nutritional status probably does become more important. The more nutrient insufficient we are, the more likely we are to get some sort of inflammatory condition going on.

So I do think nutritional status is important and perhaps even more so as we age. So I'm quite sure there is some effect of age. But the thing about dairy is it's the main way we get calcium. You can have a dairy-free diet and be totally nutritionally complete. You can get your calcium from nondairy sources. [But] for most Americans, 75 percent of their calcium does come from dairy. So as a nutritionist recognizing the importance of calcium, I don't like to limit something if that's a major way people get a very important nutrient. So I think there is a place for dairy. I don't believe these association studies have really got to the heart of the matter yet. I don't believe that there is necessarily a link [between dairy and prostate cancer].

How much more research needs to be done on nutrition, specifically dairy and its role in the development of cancer?

Certainly, there's more needed. For example, when we grass-feed cows, their meat and milk express, in higher amounts, this thing called conjugated linoleic acid. It turns out that's a very anticancer sort of fatty acid. So that's an example of how changing practices with how we manage our dairy herds can affect the humans that eat the tissue of those animals and drink the milk of those animals. The use of fermented dairy in particular, with which there's a ton of health benefits, has also been historically very beneficial.

There are ways to eat dairy that are very, very healthy, like fermented products, and there are ways to exclude it completely from your diet as long as you're conscious of getting calcium and other missing things. But I don't think one has to avoid dairy to avoid any kind of cancer, including prostate cancer.

People always want to know what are "good foods" and what are "bad foods," and a dietitian hates those words because we endorse a balance of foods and, in many ways, endorse that there's room for everything: have that birthday cake once in a while, have that beer once in a while, but in general, a balance of many nutrients.

I think we, as scientists, must always have an open mind and no preconceived notions and look at the preponderance of evidence and not just one study at a time. And if anybody wants to, they should consult a registered dietitian who's an expert in this area.