We Have Questions: Prostate Exams

About 1 in 8 men—and 1 in 4 non-Hispanic Black men—receive a prostate cancer diagnosis in their lifetime, according to the American Cancer Society. While this statistic is obviously concerning, the mortality rate remains low, at about 1 in 41 cases. As with most potentially fatal diseases, the survival rate is, in large part, thanks to early detection.

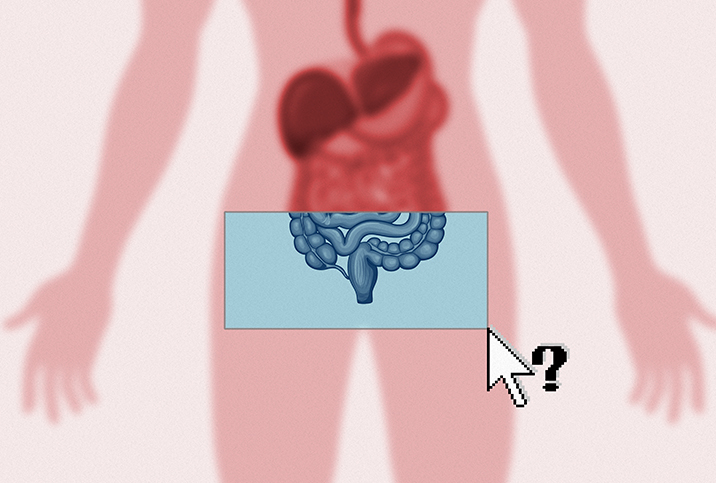

The prostate exam, known as a digital rectal exam (DRE), has long been the predominant screening method. The DRE involves a healthcare provider inserting their finger into the rectum to feel the prostate gland, located below the bladder and in front of the rectum. The exam may not make for a great time, but it typically shouldn't hurt, either. Plus, the benefits, particularly for men in high-risk groups, make it well worthwhile.

Besides cancer detection, the DRE is an opportunity for providers to find issues such as prostate inflammation or pelvic floor dysfunction, which can cause symptoms such as pain and urinary or erectile difficulties.

Amy M. Pearlman, M.D., based in Iowa City, Iowa, is a men's sexual health specialist, board-certified urologist and urologic surgeon with a subspecialization in genital and urinary reconstruction and male-specific quality-of-life concerns. She answered questions about what the DRE involves, what doctors can learn from it, who needs it and what happens if it yields abnormal results.

What is the digital rectal exam and what does it entail?

Pearlman: The exam is having the man pull his bottoms down and then, depending on what he prefers, it's staying standing or lying on the exam table on the side. Then the person doing the exam will spread open the butt cheeks so you can see where the anus is, then put lubrication on their finger and gently place the finger in the rectum.

The movement is like a slight downward pressure to help open up the sphincter, then going all the way in usually until, depending on the person's body and the finger length, the finger is all the way in and the prostate can be felt. The prostate is at like 6 o'clock, with the finger pad pointing down toward the floor. The prostate exam usually begins with feeling downward. It's like a windshield wiper maneuver, so going to the right and going to the left and feeling the prostate tissue. We're feeling the back part of the prostate through the rectal wall. We're feeling for any lumps or bumps or asymmetry between the two lobes of the prostate.

Some people just do a prostate exam. I do a 360-degree rectal wall exam because I'm looking for a few additional things. Many of my patients are also coming in with pelvic floor muscle dysfunction, and there are a lot of muscles surrounding the pelvic floor, especially surrounding the rectum. So I'm feeling tenderness around that area. I kind of move my finger around 360 to feel for any tenderness in the muscles, and I'm also feeling for any lesions, so any lumps or bumps in the rectum that would suggest the person needs to have that examined, as well. I don't want to miss any rectal lesions, and I'm also checking the pelvic floor in addition to the prostate.

Is the exam painful?

There is pressure, but it should not be a painful exam. When people have pain with the exam, it could be for a couple of reasons. One, they're coming in with pelvic floor dysfunction, so their muscles are very tight and they have tenderness in that area anyway. Two is someone has hemorrhoids or an anal fissure that can also be very uncomfortable. Three is someone who was completely not expecting the exam and was taken off guard, then it can be more uncomfortable than it really should be. And then it depends on the technique of the healthcare provider. Some people are just like, 'I'll go in and out and get this done.' But if you do it slowly and open up the sphincter, you know, there are definitely ways to do it that don't cause pain.

Why is the exam important?

A lot of different specialists do rectal exams. The rectal exam for a gastroenterologist is going to look into GI things like hemorrhoids and masses and fissures. For urologists, we do it to feel the prostate mostly.

As men get older, three main things happen to the prostate. One, it can get larger for noncancerous reasons. The area typically enlarges with age for noncancerous reasons, and that's not actually the part of the prostate we're feeling with these rectal exams. Someone can have an enlarged prostate and urinary tract symptoms, but that's not going to be well-assessed with this exam.

Another thing would be for the prostate to become infected, like prostatitis. It's falling out of favor now these days, but some people used to do a prostate massage to try to get out fluid from the prostate specifically to test to see if there was bacteria or inflammation that came out of that area. You'd have the person urinate after doing a prostate massage.

Three, the prostate can develop prostate cancer. Prostate cancer is one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers in adult men. Most men will die with prostate cancer but not of prostate cancer. We know that from cadaver studies where they die for other reasons, and prostate cancer was incidentally found in their prostate. Prostate cancer typically develops in the back part of the prostate that we can feel through the rectal wall.

So a big part is prostate cancer screening. It was more important before we had a blood test. Now we have a blood test that's been around for many years, a PSA test, prostate-specific antigen. It's a blood test that we have typical ranges, depending on age and race. So if someone comes in and they have an elevated PSA, it's not diagnostic for prostate cancer, but it often will warrant an additional workup, whether it's with additional imaging or a biopsy.

But before the PSA, the only way to really know if someone had concerns for prostate cancer was the rectal exam, so people would feel large masses and abnormalities on the rectal exam because nothing was caught early. Now we can catch things very early and treat them. Typically, both a prostate exam and a PSA are used for prostate cancer screening. That's what most men would get when they see a urologist or primary care provider.

What are a couple of things men think they know about the exam but don't?

One is that a lot of people get nervous about it because they think it's going to be painful, but it doesn't have to be. Two, it's not a good indicator of prostate size. Even though a lot of people are told their prostate is big based on this exam, it's not a good indicator of the size of a prostate. For that, most of us will get actual imaging. Because we're only feeling one part of the prostate, it doesn't tell us if the prostate is causing a blockage, which is contributing to urinary symptoms.

You mentioned blood tests, but what else has changed about the exam (or how the results are interpreted) over the past 10 or 20 years?

Now, imaging is a big part of evaluation for prostate cancer. These days, I don't even do a prostate exam on everyone. I do it selectively because I am taking a PSA for most of these patients, and abnormalities on a PSA are going to show up much sooner than an abnormality on a prostate exam. So if there are any concerns based on the blood test, I'm going to get an MRI [magnetic resonance imaging] of the prostate, which will give me a much better idea of what's going on in the prostate than my finger will. I would say more so in the last five years is where we're using more advanced technologies to better understand prostate anatomy rather than fingers alone.

When should people generally get their first exam? Are there instances in which people should get them sooner?

Great question, and it's a tough one because it's all based on care decision-making when it comes to prostate cancer screening. Usually, it's around [age] 50. A big factor is family history. If someone has a family history of prostate cancer, it's really important to know at what age they were diagnosed. We're talking like brothers, fathers and uncles. Let's say the father was diagnosed at 65 with prostate cancer. A lot of 65-year-olds have prostate cancer. That's different than if a father was diagnosed at 45 with prostate cancer. Then I would want to start screening with a PSA and perhaps a rectal exam earlier, in that man's 40s rather than in his 50s. So it depends on family history and what age they were diagnosed. You would want to start screening before that age.

And then, when it comes to race, we know that African American men are at higher risk of prostate cancer and higher risk of more aggressive disease. In this case, race, for a variety of reasons—environmental and genetic factors all play a role in those increased risks.

I start checking PSAs and doing rectal exams earlier, but for a different reason. I treat a lot of hormone deficiencies, so guys coming in with concerns for low testosterone, and if I'm going to start them on testosterone, if they're 40 or older, the guidelines are to start checking their PSAs much earlier. And then, because I also see a lot of young men with pelvic floor dysfunction, I'm doing the rectal exam for different reasons: not to check for prostate cancer but to assess their pelvic floor muscles. So I might be doing these exams on guys in their 20s, 30s and 40s.

There's not a single age. In men under 40, the panel [of the American Urological Association] doesn't recommend PSAs. And even in men between 40 and 54 years old who are at average risk, the panel does not recommend routine prostate cancer screenings. It's mainly for men who are 55 to 69 years old. When you weigh the risks and benefits of prostate cancer screening, that's where there's the greatest benefit.

For people of average risk, how often should they have the exam?

Historically, it's been on an annual basis, but to reduce the risk of harm of screening, now the recommendation is every two years. The guidelines, it's sort of this pendulum that has gone back and forth. You'd think, 'Why wouldn't you want to pick up on every person with prostate cancer? Don't you want to find it and treat it?' The answer is no, not really. We want to find the prostate cancer that will end up impacting someone's life and leading to their death. But some prostate cancer is a very low-risk disease and won't ever affect that person. So we don't want to treat everyone with prostate cancer, because the treatment has its own side effects, such as decreasing erectile function and causing urinary leakage. There are downsides to treatment and real, potential quality-of-life implications. The goal is not to find and treat everyone with prostate cancer; it's to find and treat those with clinically significant prostate cancer.