We Have Questions: Prostatitis

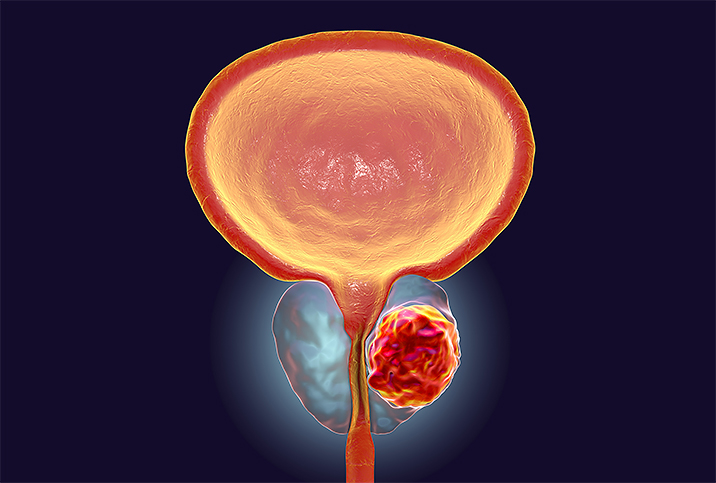

Chances are you might not be able to pronounce prostatitis, let alone know the nature of this ailment that sends millions of men to their doctor each year. The most common urinary tract problem to hit men ages 50 and younger, prostatitis involves inflammation and swelling of the prostate gland and leads to a host of problems, such as pain during urination or ejaculation, tenderness in the groin and flu-like symptoms. Another part of the "fun"? Prostatitis isn't just one disease but a group of four separate conditions with no magic bullet cure-all in sight.

We wanted to know more, so we went straight to an expert: David Yao, M.D., a Santa Monica, California–based urologist who works in the UCLA Health system. Yao has been an attending urologist since 2011 and specializes in vasectomies, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), hematuria and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood tests for prostate cancer.

He answered questions about prostatitis and its causes, diagnosis and prevention, and explained a diagnostic method called UPOINT.

What is prostatitis?

Yao: The technical definition of prostatitis is inflammation in prostate tissue, but clinically speaking, it's pelvic pain sometimes associated with urinary or sexual symptoms that have occurred in at least three out of the last six months.

What causes prostatitis?

There are actually four different types of prostatitis. Type I is called acute bacterial prostatitis. That means that the cause of the prostatitis is from bacteria that typically is cleared with a month of antibiotics. Type II is called chronic bacterial prostatitis, and this means that we can clear it with antibiotics but it comes back again soon afterward. But then it can eventually be cured with a long course of antibiotics.

Type III is chronic nonbacterial prostatitis (also known as chronic pelvic pain syndrome, or CPPS). This accounts for about 90 to 95 percent of prostatitis episodes. And this is what most people are talking about when they just use the term "prostatitis," chronic pelvic pain without any evidence of it being something else—for example, infection, cancer or kidney stones.

Then the fourth type is called asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis, when there is an inflammation present in the prostate but there are no symptoms. And in autopsy studies, this may be as high as 65 to 85 percent.

Is there ever an STI/STD to blame?

That typically would describe the type I acute bacterial prostatitis. But for type III, there are some small studies that showed that certain bacteria like E. coli, gonorrhea, chlamydia and mycoplasma could cause prostatitis, though most studies show that's probably not the case.

How can prostatitis be prevented?

Well, prostatitis is one of the most challenging diseases for urologists because we don't have a clear source and we don't have one treatment that treats all patients who have prostatitis well. We now think that prostatitis is probably a mix of many different diseases that cause pelvic pain, with possible sexual and urinary symptoms.

It's best to break it down into phenotypes, basically based on symptoms. The shorthand for this is called UPOINT. So we break down prostatitis into these symptoms: U for urinary, P for psychosocial, O for organ-specific, I for infection, N for neurologic and T for tenderness.

How is prostatitis diagnosed?

Prostatitis is a diagnosis of exclusion, meaning that you have these symptoms of pelvic pain with possible urinary and sexual symptoms as well, and we cannot find another reason for it. The diagnosis is based on the symptoms of pain and then a negative workup otherwise for STDs [sexually transmitted diseases] and urinary infections.

Are imaging or scans involved in the diagnosis?

There are no lab tests that exist that tell us if someone has prostatitis or not. We do use imaging if we're thinking that it could be something else. For example, if someone has a hard testicular mass, then we may get an ultrasound to rule out testicular cancer. Or if someone has colicky pain in their kidneys with nausea, they could be passing a kidney stone, and then we would get some abdominal imaging to assess that. So nothing so much specific for prostatitis—it's more to rule out other conditions that could explain the symptoms.

Do any other conditions present similar symptoms?

Many. One of the most common is something called interstitial cystitis, which is a chronic bladder pain syndrome. Passing a kidney stone can cause these symptoms, [along with] urinary infections, certain STDs, such as gonorrhea and chlamydia, and testicular infections. Sometimes spinal stenosis can cause this, especially in the lumbar region. So quite a range of different disease processes.

Should men bring up the condition with their doctor or trust that their doctor will know to look into prostatitis?

I definitely see the physician-patient relationship as an equal platform. And I strongly encourage my patients to tell me what they think and what they're concerned about so that I can better tailor my discussion and my treatments to address their concerns. So I certainly welcome people telling me if they think they have prostatitis.

Is there a sexual impact of prostatitis?

Yes, there are very common sexual symptoms of prostatitis. About 60 percent of men who have prostatitis describe having painful ejaculations. About 65 percent have premature ejaculation. And worldwide it's a wide variance, but somewhere between 15 to 40 percent of men with prostatitis say that they have erectile dysfunction from it.

What's the worst that could happen if someone decides to ignore their prostatitis?

Prostatitis is a quality-of-life disease. It does not become something dangerous or life-threatening, such as cancer. There is certainly a wide range of severity of symptoms. Overall, about 80 percent of men will get prostatitis sometime in their lives.

What are the treatments for prostatitis?

Going back to the UPOINT phenotype strategy, the treatments are based on what are some of the primary symptoms of the patient. For example, if it's primarily a urinary problem with obstructive symptoms like an occasionally weak stream and straining associated with the pain, we can give different medicines to shrink the prostate or relax the prostate. For psychosocial, where there seems to be depression or catastrophizing as part of the symptoms, antidepressants, anti-anxiety pills, counseling, cognitive behavioral therapy, mindfulness and meditation can be very helpful.

If it's O for organ-specific—that is prostate pain specifically—prostate medicines to relax the prostate can be helpful, as well. If they have symptoms suggestive of infection, then we give antibiotics. If their symptoms are suggestive of a neurological cause, we'll give medicines for neuropathic pain; a neuromodulating medication, for example, like gabapentin or pregabalin. And then, finally, if there's tenderness to the pelvic floor, if the pelvic floor feels really tight, referring these men to physical therapy can be very, very helpful.

Is surgery ever a treatment option?

Surgery is only an option if during the workup for pelvic pain we find something else is going on. For example, [if we find] a urethral stricture or a bladder neck obstruction or tumor, then we would operate. But in the absence of finding anything else to explain it—we just have these pain symptoms—then no, surgical therapy is rarely used.

Once prostatitis is treated, how often does it come back?

We don't have anything that has a high cure rate, to be honest. And there's a high variance of how many patients actually have recurrent symptoms because it's probably due to many different things.

One of the most important things during the initial visit when someone sees me—after usually having seen many doctors—is that I will do my best to get you better. We'll try to reduce the severity of the symptoms and try to reduce the frequency of recurrence, but I do not have a cure for you.

There was a large study in 2002 that looked at the cure rates of prostatitis and it was, I think, 18 or 19 percent at the end of one year. With the UPOINT, where we have a targeted treatment, about 70 to 80 percent of men say they have significant improvement in their symptoms, but it's a very complex disease.

Does prostatitis ever lead to prostate cancer?

No. Many years ago, we thought that may be the case. But recent data shows that no, there is no correlation between prostatitis and prostate cancer.

Should men tell their partners if they are experiencing prostatitis?

If during the workup we find that there are other reasons for the pains, such as STDs, I think it's very important that the man tells his sexual partner. If it's found to be nonbacterial prostatitis, which is true 90 to 95 percent of the time, I think it's up to the comfort level of the man when he wants to tell his partner about this, because this will not impact, as far as we know, the health of the sexual partner when it's nonbacterial.