New Assessments Can Bolster the Prostate-Specific Antigen Test

Prostate cancer. It's as common in men as breast cancer is in women, with 1 in 8 people developing the disease in their lifetime.

This makes it the most common non-skin cancer in men.

The good news? Prostate cancer is highly treatable, with an overall five-year relative survival rate of 98 percent and a nearly 100 percent survival rate when detected in the localized stage, according to the American Cancer Society.

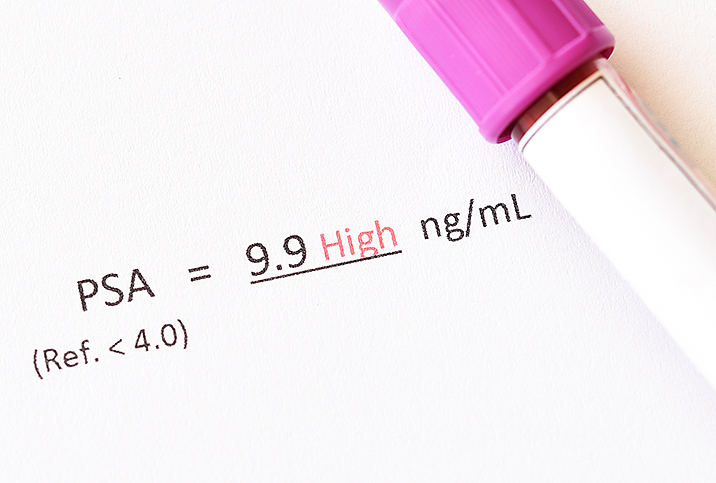

The prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test has long been the go-to screening measure, but its results are sometimes used as the basis for an unnecessary treatment regimen because they can't tell physicians how aggressive the cancer is.

Screening guidelines have changed several times in recent years, so determining whether a PSA test is appropriate for someone can be confusing. Plus, most people have heard stories of unnecessary biopsies and treatment for prostate cancer following high PSA results.

Times have changed, though, and the tests available to detect prostate cancer have improved significantly. Some new assessments work in concert with a PSA test, while others are standalone analyses.

PSA in a nutshell

PSA is a protein made by both cancerous and noncancerous cells in the prostate gland, and it is normal to have some PSA in your body. However, the PSA level in your blood can rise if there is a problem with your prostate, such as prostate cancer. The issue with the test's accuracy is that other factors, such as an enlarged prostate, prostatitis, a urinary infection, vigorous exercise or ejaculation before a PSA test, and other tests and surgeries, can also make your PSA level rise.

"If the PSA test is abnormal, then a patient may need a prostate biopsy," said S. Adam Ramin, M.D., a urologic surgeon and the medical director of Urology Cancer Specialists in Los Angeles. "However, before moving on to a biopsy, we can do additional tests to determine the need for a biopsy."

According to the United Kingdom National Health Service, approximately 3 in 4 men with a raised PSA level do not have cancer.

While the PSA is definitely not a perfect test, it's a very good screening measure, and a low PSA reading generally means good prostate health. However, just as a high PSA level does not automatically indicate cancer, a low PSA level does not always mean you're risk-free.

Determining the need for a biopsy

If the traditional PSA test shows elevated levels, the next question becomes, "What's causing high levels of PSA?"

Additional tests are now available and usually more accurate for detecting what is considered "clinically significant" prostate cancer, or the cancers that require treatment.

"We actually don't want to find the less aggressive prostate cancers because they only cause unnecessary anxiety and often lead to overtreatment of cancer that would be unlikely to cause you any problems," said Zeyad Schwen, M.D., a urologic oncologist at Cleveland Clinic.

Schwen explained that although the PSA test casts a wide net, the newer, more powerful blood, urine and imaging tests target the worrisome cancers that require biopsy and possibly treatment.

He said the most commonly used tests include blood tests such as the prostate health index (PHI) and the isoPSA. These look for different forms of PSA that are elevated in men who have a higher risk of prostate cancer. The isoPSA helps determine whether prostate cancer is the cause of elevated PSA levels by identifying certain types of PSA proteins made by cancer cells. The PHI is used to help predict the presence of prostate cancer and its aggressiveness.

"The prostate health index is actually an equation that combines three different types of PSA to calculate a risk of harboring prostate cancer: total PSAs, free PSA and the [-2]pro-PSA," Schwen explained.

Ramin mentioned two other tests that could help determine the need for a biopsy: liquid biopsy urine tests (e.g., the PCA3) and the 4Kscore, a blood test to determine the likelihood of prostate cancer in patients with abnormal PSA results.

In addition, both Ramin and Schwen said magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is another commonly used screening tool for prostate cancer.

"While we don't always think of MRI as a biomarker, a normal MRI is a very powerful tool to help rule out prostate cancer," Schwen said, adding that radiologists who read these MRIs can score any concerning lesions based on their probability of being cancer using a scoring system called PI-RADS (prostate imaging reporting and data system).

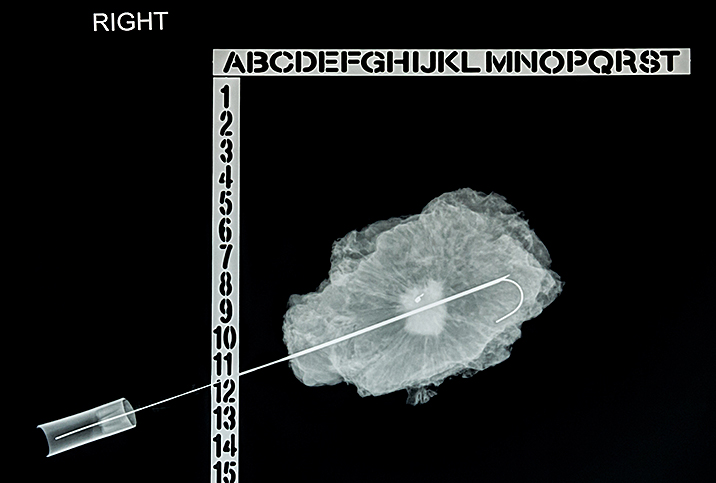

When a suspicious lesion is discovered, MRI can be used during a prostate biopsy to accurately hit the target instead of blindly sampling the prostate under ultrasound alone, he said.

"While the MRI isn't ready for primetime yet to be used alone, combining MRI with PSA and other biomarkers like the PHI and isoPSA can be used together to help avoid a prostate biopsy," Schwen said.

Ramin advised these additional tests are widely available and used on men who have elevated PSA results.

"We usually don't use them unless elevated PSA are present, because this was the criteria used in studies needed for FDA approval, so we don't really know how well they perform as a screening test by themselves," Schwen said.

Many of these tests, if used alone, would miss diagnoses of prostate cancer that need treatment.

"As our MRI imaging and reporting is getting better, there is a possibility that this could be used as a screening test, but the cost has to be considered as a potential barrier," Schwen explained.

Guiding prostate cancer treatment

If through the additional testing, a clinician diagnoses prostate cancer, the range of tests expands further to ones that could help guide treatment options. For instance, Ramin said molecular/genomic testing can help the clinical team determine the degree of aggressiveness, the chance of spread and the need for treatment.

"The more we study prostate cancer, the more we realize that the cancer's genetics determine its behavior and likelihood to spread," Schwen said.

Once a diagnosis of prostate cancer is confirmed, the tissue is often sent for genomic testing. Schwen mentioned tests called Decipher and Oncotype Dx, which help measure the cancer's aggressiveness by looking for high-risk genes. This may help guide the choice between active surveillance or treatment of the cancer.

Newer and better imaging tests, called PSMA PET scans, have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration. They look for signs of early metastatic disease, which guides physicians in treatment considerations such as surgery or radiation, according to Schwen.

He added that other useful tools to help guide treatment options include calculators that use artificial intelligence to combine all of the patient information and tests to create a more accurate estimation of the prostate cancer risk.