We Have a Cure for Hepatitis C—So Why Do So Many People Still Have the Virus?

In 2014, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved an effective treatment for hepatitis C, an 8-to-12-week course of daily oral medication that eliminates the infection for more than 90 percent of those who complete the regimen. Yet approximately 2.4 million people in the U.S. are living with hep C, and rates of acute hep C are on the rise, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). So, what's going on?

The facts

Hepatitis C is a viral infection that's commonly transmitted through sharing needles or (less commonly) through unprotected sex. Last April, the CDC reported that new infection rates roughly tripled between 2009 and 2018, with the highest infection rate among those ages 20-29, an increase largely related to opioid use.

New infections of hep C are known as "acute infections," which is when the virus is most active in the body. For about 30 percent of people with acute hepatitis C (estimates can range from 14-46 percent depending on the study), the immune system will clear the virus without treatment within about six months after infection.

For those whose bodies don't clear the infection, the virus can become a chronic infection that attacks the liver over time. This can lead to scarring of cirrhosis, liver cancer and failure of the organ. Many people with chronic hepatitis C don't experience any symptoms until irreversible liver damage has already occurred.

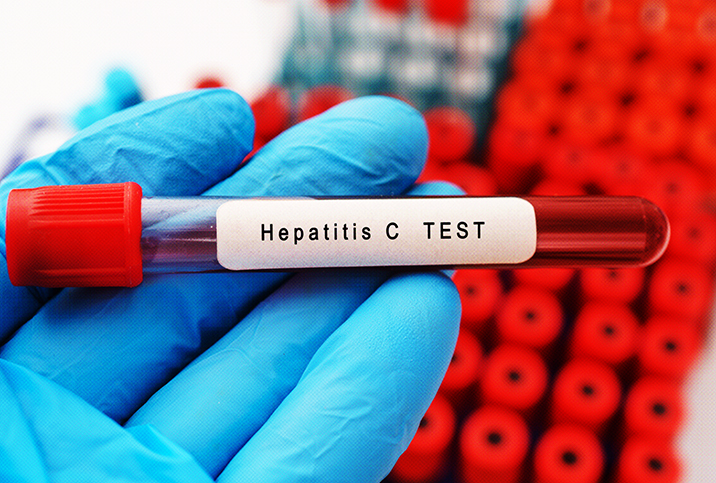

Screening for hepatitis C: Who should get the test?

Screening for hepatitis C is usually done via a blood test and allows doctors to provide treatment before the infection causes damage to the liver. The blood test can easily be added to any other lab work ordered by your primary care provider, so you should ask to get screened.

Blood test results are usually available within a few days, though some clinics offer a rapid fingerstick test for hep C to provide answers in about 30 minutes. The CDC recommends all adults be screened at least once in their lifetime for hep C and that those with risk factors, including people who inject drugs and share needles, should be screened more frequently. Pregnant women should also be screened as it's possible to transmit the virus to a baby.

Only 61 percent of adults with hep C were aware of their infection, according to the CDC. Because so many people don't have symptoms, it's recommended everyone be screened once, even if you don't think you're at risk, just to be sure you know your status.

Why don’t more people with hepatitis C get treatment?

Many people with the hep C aren't aware of their status. But even after someone is diagnosed, it can be a bumpy road to treatment and a cure. "They're often asymptomatic, and it's hard to convince people they need treatment," said Erin Swepston, DNP, a primary care provider at Cityblock Health in New York. Swepston noted that some of her older patients have experienced issues with an older hepatitis C treatment, interferon, which had a cure rate of only 40 percent, even though it required weekly injections for a minimum of six months and came with substantial side effects, including fatigue, fever and muscle pain. After trying interferon, some patients are unwilling to risk similar issues with new medications, Swepston said.

Even for those willing to try the treatment, access can be difficult. Prices for a 12-week course of hepatitis C medication can start at $24,000, with some medications costing much more. Although assistance programs offered by pharmaceutical companies to cover co-pays or even the cost of the medication itself are often available, the blood tests needed for the treatment can also be costly. A genotype test is needed to identify the strain of the hepatitis C virus before treatment, and this can cost more than $700.

During treatment, RNA tests are needed every 4-to-6 weeks to check the level of the hepatitis C virus remaining in the blood. These repeated tests can easily add up to another $2,000 over the course of treatment—a lot of money for someone who may be uninsured or who has a high deductible. Federally qualified health centers provide medical care at low or no cost and can often help patients to access affordable treatment for hep C, including aid in navigating medication assistance programs and providing medical visits and lab work for free or at a reduced rate.

Most insurers require prior authorization for hep C treatment, due to the cost of medications and lab work, and some state Medicaid programs have restricted access to treatment to only those who have already experienced liver damage.

"You're setting someone up for a lifetime of poor health if you wait until symptoms appear before treating because they're not going to go away," Swepston said. Better access to these treatments improves both individual health as well as population health since those who are cured of hepatitis C are no longer at risk of transmitting the virus to others.

For some of Swepston’s patients, ongoing homelessness and substance use can be a challenge to completing treatment. Swepston noted the importance of providing appropriate resources, such as access to clean needles, temporary housing and case management, to help support patients in completing treatment. Although some insurers still require a period of sobriety before hepatitis C treatment, this restriction is not supported by the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease clinical guidance.

Hepatitis C treatment: What you need to know

Overall, Swepston emphasized that the treatment works well: "It’s good, it’s safe, and most people I’ve treated haven’t had a single side effect," she said. Swepston hopes more primary care providers will incorporate hep C treatment into their practice to increase access because some patients who are diagnosed with hepatitis C can experience challenges in finding a specialist to provide treatment.

But the first step is knowing your status. If you’ve never been tested for hepatitis C, ask your doctor about a screening test. In the past, only people born 1945-1965 were routinely offered screening, so make sure your doctor is aware of the updated recommendation to screen all adults. To protect yourself, avoid sharing needles and practice safer sex. "And if you’ve been tested and you’re positive," Swepston said, "you should demand to be treated."