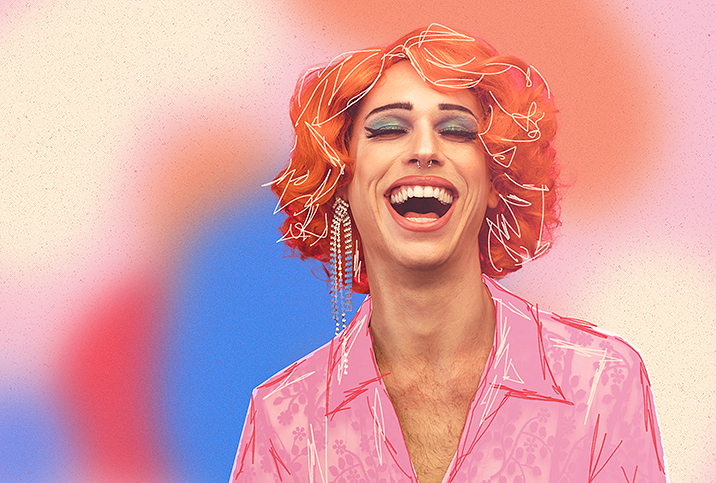

The Man Who Made Medical History—And Kept His Sex a Secret

You may be unaware of the remarkable career of James Barry, M.D., because of the controversy revolving around certain discoveries made after his death, which became a flashpoint for the staid society of Victorian England.

Evidence put together after his death led historians to believe Barry was born Margaret Ann Bulkley in Cork, Ireland, in 1789. When Bulkley's mother's brother—a renowned Irish artist and professor of painting at London's Royal Academy—died, leaving his fortune to the two women, Margaret presumably adopted said uncle's identity, becoming James Miranda Steuart Barry.

At a time when women were not encouraged to have any formal education, Barry was accepted at the University of Edinburgh Medical School in Scotland, joined the British Army in 1813, and rose to the rank of Inspector General, the second-highest medical office.

During his 46-year career, Barry lived publicly and privately as a man and used male pronouns to refer to himself. However, the malicious revelations after his death that he had the body of "a perfect female" would forever change the perception of this medical giant.

A crusader for medical sanitation

"Barry [required] hospital staff to regularly wash their hands [and] the regular changing of patients' bedding and bandages," said author and archivist David Obermayer. "During outbreaks of contagious diseases, Barry instituted quarantine wards to keep contagious patients away from noncontagious ones. [He] undertook the opening of a free clinic for sex workers, advocated hiring nurses with medical backgrounds, including Indigenous women who had worked as healers—and everywhere he was stationed, Barry was also concerned with nutrition, particularly for lower-ranking soldiers."

The memory of progress is a short one. Consider Barry was encouraging innovative ideas about cleanliness for his wards when handwashing in hospitals only became advised starting in 1847. To further underline Barry's achievements in the early 1800s, consider that national guidelines for handwashing weren't released in the U.S. until the 1980s, and it was only in 2002 that alcohol-based hand disinfectants became standard for medical care.

Barry understandably had his hands full getting other doctors to comply, efforts hindered by his emphasis on proper certification of those working with and around him.

"As Colonial Medical Inspector in South Africa, Barry required pharmacists and doctors to have been trained and certified in Britain or Europe in order to practice in the colony," Obermayer explained. "British-held South Africa had no training or certification process within the colony at the time. Pharmacists and doctors had to be trained prior to them coming to the colony or traveling back to Europe in order to be certified. During his time as Colonial Medical Inspector, Barry levied fines on those breaking his rules, and in a few cases, imprisoned pharmacists in particular for either operating without official certification or selling tainted drugs that led to a patient's serious harm or death."

His finest hour

Barry's medical skills were reported as unprecedented and he was known to be an extremely skilled surgeon for his time. However, while his accomplishments were inarguable, questions about his gender identity followed him throughout life.

At medical college, Barry was almost denied his final qualifications, as those in authority were unconvinced that he presented as an adult male. Throughout his career, many pointed to his high voice and slight body as evidence he was not as old as he claimed.

As a further complication—both for his own life and historians' understanding of it—Barry faced homophobia, as it was perceived he was attracted to men. Although what seemed to be career-crippling allegations of a same-sex affair with Cape Town's governor, Lord Charles Henry Somerset, were made public, both men were later exonerated.

While his accomplishments were inarguable, questions about his gender identity followed him throughout life.

It was during this period Barry carried out his most famous medical procedure.

"Although Barry is often cited as carrying out the first successful C-section—where both the baby and mother survived—he most likely was not the first person in history to perform such a surgery," Obermayer clarified. "[The surgery was performed on] Wilhelmina Munnik, the wife of Thomas Fredicer Munnik who was a wealthy snuff manufacturer in Cape Town and a member of a wealthy and well-established colonial family."

The implication of Obermayer's observation is the cesarean section was most likely remembered by history because of the rich and powerful patients. In Barry's honor, the child was named James Barry Munnik, a name passed down through the family to General James Barry Munnik Hertzog, the third prime minister of the Union of South Africa from 1924 to 1939.

An ethical medical hero

In an age of rampant medical racism, Barry's egalitarian approach to all patients—regardless of race or social standing—was revolutionary, especially compared to the ethics of other more famous medical figures in his peer group.

The best-known gynecologist of the 19th century, J. Marion Sims, pioneered now ubiquitous medical instruments such as the speculum by operating on fully conscious enslaved women at a time when anesthesia was—while expensive—most definitely available.

"Enslavement by its very nature robs people of consent in so many profound ways," Obermayer observed. "That being said, there is no evidence that Barry experimented on enslaved peoples in the same way that many of his contemporaries did. He was also notorious for demanding the same level of care for everyone, including enslaved people. He actually got into a great deal of trouble in South Africa because of his advocacy for patients in a government-run leper colony—which included many enslaved people—and for prisoners in the colonial prison system."

Barry is now achieving some fame as a gender rebel, with many books written about him using the feminine pronoun. Yet this was never his wish: In private correspondence and after his retirement, he continued to use male pronouns. His own physician, Major D. R. McKinnon, believed it was "none of [his] business whether Dr. Barry was a male or a female, and that [he] thought that she might be neither."

Pronouns may be semantics for many people, but they were important for Barry, to the point that it was only after his dying wishes were violated that his former gender identity came to light. He lived the majority of his life as a successful doctor, a brilliant surgeon and an accomplished man.

I think that's how he'd like us to remember him.