Between the Pages: 'The Quest for Sexual Health'

For the past half-century, researchers, health providers, advocacy groups, commercial interests and more have invested in sexual health. But what exactly does this broad term mean? What does it actually mean to be sexually healthy?

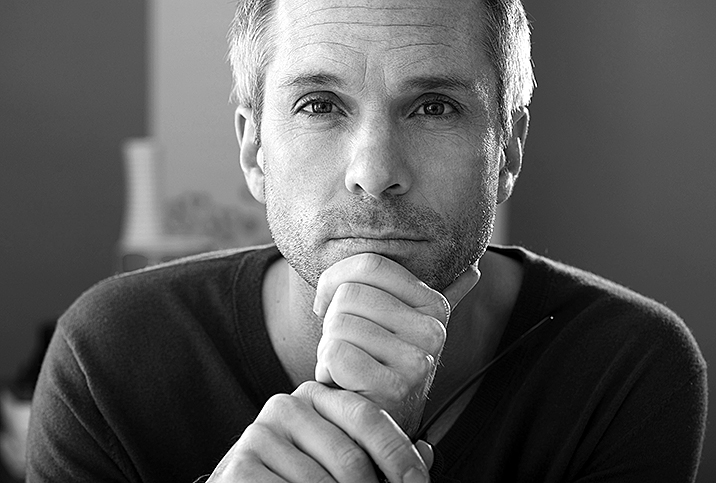

Sociologist Steven Epstein, Ph.D., tries to answer these questions, and others, in his new book, "The Quest for Sexual Health: How an Elusive Ideal Has Transformed Science, Politics and Everyday Life," recently published by the University of Chicago Press. He examines the social, cultural and political processes that shape sexual health, as well as the consequences of being sexually healthy.

Epstein is the John C. Shaffer professor in the humanities and a professor in the sociology department at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. He is also the author of "Impure Science: AIDS, Activism and the Politics of Knowledge" and "Inclusion: The Politics of Difference in Medical Research."

In this exclusive interview with Giddy, Epstein discusses the factors that led to the rise of sexual health, provides guidance for finding a credible sexual health expert and more.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What inspired you to write this book?

In some ways, it was a reflection of my own past experience as a researcher. I've been working on topics related to health, medicine and sexuality pretty much my whole career. When I was a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, during the early days of the AIDS crisis, I became interested in questions having to do with science expertise. Whose knowledge counts? But also, the practices of AIDS activists and challenging stigmatization and promoting sex positivity. I wrote a book that focused on questions that were very much on the intersection of sexuality and health. I've done work on LGBTQ health advocacy and work relating to the introduction of Gardasil, the vaccine for HPV.

I'd been thinking of questions of sexuality and health for a very long time but had never really questioned the whole idea that there was such a thing as sexual health and sat down to ask, where does that come from? How long has that term been around? What are the different things that sexual health can mean? How does it change health for there to be a focus on sexuality as part of what we think of medical practice and health care? How does it change sexuality if we approach it from a medical perspective?

I thought it was important to take this broader, partly historical and partly sociological investigation of the very idea of sexual health. The AIDS epidemic and so many other issues come up that place sexuality and health at the center of popular attention as something that people fight about, the centerpiece of political struggles, and something that ordinary people worry about and want to know more about. It seemed like an intriguing and important topic to investigate more broadly and thoroughly.

In the book, you discuss the World Health Organization's 1974 working definition of sexual health. What was the significance of that?

I think it's very significant, even though the World Health Organization [WHO] has never officially claimed the definition. They call it the working definition and they list it on their website, but it's not an official definition of the WHO because they've never put it to a vote by the World Health Assembly. Of course, that tells you something really interesting about the controversies around sexuality.

Sexuality is something the 194 member states of the WHO disagree about a lot, and so the WHO was afraid, I would say, to put the definition to a vote. They preferred not to seek consensus, so it's more of an informal, working definition. Even so, it's been really influential. Whenever organizations, professional groups and medical dictionaries talk about sexual health, it's really common to cite the WHO definition.

[Editor's note: According to the WHO's current working definition, sexual health is "a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality; it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity. Sexual health requires a positive and respectful approach to sexuality and sexual relationships, as well as the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences, free of coercion, discrimination and violence. For sexual health to be attained and maintained, the sexual rights of all persons must be respected, protected and fulfilled."]

It's been influential, in part, because it's been, from the beginning, such a broad and capacious statement about what sexual health might entail. The WHO's working definition says that sexual health involves physical, mental and social aspects, and keeping with the general WHO definition of health, it insists health is more than just the absence of disease. It moves us beyond biomedicine. It also moves us in more political directions.

It's gone through several changes over the years: The WHO's working definition from 2006 mentions sexual rights need to be respected in order for people to enjoy their sexual health. That gives a political edge to the definition and makes it of interest to advocacy groups and others who want to promote various rights in relation to sexuality. By being really broad, the definition provided something for everyone. That is very beneficial. It's helped fuel the process that I describe as the "buzzwording" of sexual health, where the term starts to mean so many different things and gets picked up by so many different groups and used in quite different and sometimes competing ways.

The term, concept and idea of sexual health proliferated in the 1990s. What were some of the reasons for that?

The first, absolutely, was the HIV/AIDS epidemic, which I think functioned as a relay to move sexual health into broader sexual health. One of the things the term provided was a euphemism. It was a way of talking about gay sex at a time when that was very stigmatized and remained illegal in many states. Referring to sexual health was a more palpable term.

It also tried to extend the idea of HIV prevention into a broader arena. The AIDS epidemic really put sexual health on the global agenda in a very dramatic way. Also, there was a lot of attention in the 1990s to sexual and reproductive health issues. For the first time, a lot of people were talking about "sexual" and "reproductive" in the same breath, bringing those terms together.

The famous International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo in 1994 focused a lot of attention on women's health concerns and pointed to both reproductive health and sexual health issues. In fact, at the conference, the question came up, "What is sexual health? How do we talk about that?" That became part of the discourse among a lot of advocacy groups concerned with reproductive health issues at that time.

In 1998, the United States Food and Drug Administration approved the use of Viagra, which suggested a whole additional way of thinking about sexual health: sexual health as the absence of sexual dysfunction, sexual health as taking medication to treat sexual dysfunction, and that was, of course, a very important financial development for companies like Pfizer. It was also a big social development because, with the direct-to-consumer advertising for Viagra and related medications, lots of people were talking about the idea of promoting and improving their sexual health. Sexual health was available as a term to capture all these developments. The more the different kinds of concerns became encapsulated into this category of sexual health, the more that increased the tendency for others to start using the term and to begin thinking more broadly about all the different aspects and dimensions of sexual health.

So many people claim to be experts in sexual health. What advice would you give to the layperson seeking a reliable and credible source on sexual health?

It's absolutely true that we've seen this proliferation and diversification of expertise around sexual health. We've seen more and more experts of different kinds, and what's significant is that only some of those experts are people who have formal credentials [such as] M.D. and Ph.D. Sexual health is a domain where, increasingly, people are able to position themselves as authorities based on their personal experiences, their membership in particular alternative sexuality communities and based on practicing various kinds of alternative healing.

Who to trust? This is a phenomenally difficult question with expertise generally nowadays. We are beset with this problem at a time when we are more dependent on experts than ever, but popular distrust of them has probably never been more widespread. That's the crisis of expertise that we live in and we see reflected in debates about COVID-19 and so many other things. It's important to recognize that there is no single criterion of valuable and trustworthy expertise. You want to look at what people's credentials are, but that can't be the only consideration because sometimes the people with the letters after their name have significant biases. And sometimes people who don't have that kind of formal training nonetheless have something really important to contribute.

You want to look at questions of funding. Who lies behind particular pronouncements? Is it coming from the pharmaceutical industry? They may have their own interests at stake. At the end of the day, it's important to try to balance out the advice that one receives. Don't just look to one source. Find many different sources. There just cannot be a checklist when it comes to this, and we have to be engaged and vigilant in order to figure out who merits trust and whose views seem to contribute to the discussion in positive ways.