You Could Definitely, Possibly, Be Distantly Inbred

Every few years, it seems, media outlets become fascinated all over again with Íslendinga-App. Using 1,200 years of genealogical records, the app allows Iceland's relatively tiny population of about 345,132 to determine whether they qualify as a consanguineous union with the potential partner they have chosen.

A consanguineous union is a scientific term for a relationship between close family members, usually, two individuals who are second cousins or closer. Research as of 1990 estimated that up to 8.5 percent of children worldwide derive from consanguineous unions.

Follow the money

San Diego-based psychiatrist and epigeneticist Sheldon Zablow, M.D., studies gene expression, the interaction of environmental factors and genetics, which then manifest as phenotypes or observable traits. One such environmental factor, he said, is the cultural sway of gender roles.

"Unfortunately, consanguineous unions are gender-biased," Zablow said. "Thousands of years of archaic inheritance laws that continue in many places force newly married women to turn over all her property to her husband. This money was lost to her family forever. When a male married, he kept his property, so he had greater leeway in who he chose to marry."

High-ranking or even middle-class members of society may have wished to avoid splitting up their family fortunes and implemented measures such as fraternal polyandry, where one woman marries all the brothers of a family. Other families may have had their choices hemmed in by geographical bottlenecks or cultural demands; Zablow named the shtetl, Amish, French Canadian and Cajun communities in particular.

If consolidated wealth and difficult travel conditions are the incentives for inbreeding, social stigma and an increased risk of rare disorders would be the deterrents. To understand how inbreeding jeopardizes a child's health, Zablow recalled the fundamentals of Mendelian genetics.

"People have two sets of chromosomes with thousands of individual sections that control the expression of a specific protein," he explained. "When each partner in the pair is the same, they are called homozygous pairs, and when different, called heterozygous pairs. Only one gene in the pair is 'turned on' and can actively program protein production. If they are the same—[known as] homozygosity—then it doesn't matter which gene is expressed."

In other words, there's always a chance of dangerous recessive genes being expressed, but the chance is much higher when the parents share identical genes, making homozygous pairs. Of course, homozygotes can potentially appear without inbreeding but at much lower, less dangerous rates.

Depression from inbreeding, and inbreeding depression

Montgomery Slatkin, Ph.D., a geneticist and professor emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley, said most modern-day cases of consanguineous unions contribute to certain recessive diseases, some of which may come with comorbidities.

"Visible signs of inbreeding is called consanguineous dysmorphia," Slatkin said. "While these presentations can happen, they are rarely one specific abnormality but often a combination that has specific names for each set. Many recessive diseases or genetic conditions affect mental function as well as other functions. Inbreeding leads to increases of mental disorders, but they're not qualitatively different from mental disorders that arise in noninbred individuals."

As Slatkin noted, recessive conditions can occur without inbreeding but manifest indistinguishably from inbred cases. The most notable of these single-gene recessive disorders are Tay-Sachs disease, cystic fibrosis and rarer conditions such as cystinosis. While many inbred illnesses are exceptionally rare, consanguineous unions have a wider and more subtle impact.

"The closer the parents are related—consanguinity—the greater the possibility of reduced reproductivity in the offspring, which is called inbreeding depression," he explained. "Examples of inbreeding depression include reduced male and female fertility, increased child mortality, reduced growth rates, decreased cognitive function, poor immune function—[making it] harder to fight off infections and more autoimmune illnesses—and the expression of deadly, rare genetic abnormalities in the heart, brain and biochemistry."

If all these red flags sound familiar, or even if they don't, home testing has made it more accessible to determine your own homozygosity and, consequently, make an educated guess at your own chances of inbreeding even if no family stories survive. Genome mapping, an analysis of all of your individual genes, is available for about $1,000 and would reflect whether you possess normal levels of homozygotes.

But Slatkin advised caution about broadcasting your own genetic material.

"People are going to have to think very hard about the social and ethical and political consequences of all this genetic information and take it seriously," he said. "If you decide to publish your genome, should your siblings or parents or offspring be able to stop you because your genome is very similar to their genome?"

The legal matter

Not only could publicly accessible genetic mapping present medical concerns—for example, health insurance premiums could be raised for individuals with less healthy genomes—the issue is unique in that information can be harvested from one consenting person and applied to any number of their relatives. This technology has already been used for otherwise hopeless criminal cases: Investigators took semen samples from the unsolved cases of the Golden State Killer and uploaded them under false accounts to private genealogy databases, leading them to find relatives of the serial rapist, later learned to be Joseph James DeAngelo Jr.

While recently proposed legislation would require police to obtain warrants before accessing genetic databases, privately owned genealogy companies such as GEDmatch and FamilyTreeDNA have allowed law enforcement agencies to search their libraries. No one opposes criminals being caught, but when an entity unaffiliated with you or your family accesses your (very) personal information, without consent, the concept begins to slide down a slippery slope for privacy rights.

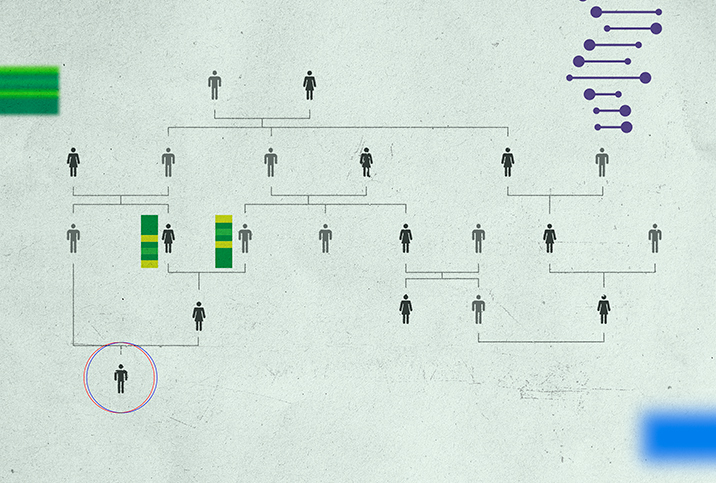

Of course, there's only a finite number of people in any given community, and it takes many ancestors to make one person: two parents, four grandparents, eight great-grandparents, 16 great-great-grandparents and so on, with each number doubling for each preceding generation. Go back 20 generations and that number is more than 1 million people.

The global population has only ever been smaller than our current-day totals, but doesn't that mean if you go back far enough we're all inbred? Theoretically, yes, probably. But assuming a person is or isn't inbred, especially based on country or culture of origin, can easily lead to prejudice.

The most commonly practiced consanguineous unions are between first cousins, the legality and safety of which have been debated for thousands of years. The Roman emperor Arcadius sanctioned first-cousin marriages in 400 A.D., but about 200 years later, the first archbishop of Canterbury was advised by Pope Gregory I to ban them due to his interpretation of a piece of Christian scripture, Leviticus 18:6: "none of you shall approach to any that is near kin to him, to uncover their nakedness." However, the same Levitical-inspired law permits marriage and reproduction between uncles and nieces, a union equally controversial in modern day.

Even today, only 25 states in the United States have passed legislation banning first-cousin marriages; 19 states allow these unions by law; another six allow them with qualifications. In some insular communities where a degree of interrelatedness is deemed unavoidable, genetic testing before marriage is common, typically screening for specific conditions and not producing entire genomes.

The ultimate question for consanguineous unions is whether anyone—the partners or their children—is getting hurt. Beyond that, the perception of these unions boils down to personal opinion, cultural beliefs and having a cool grand in extra income to spare on the pursuit of potentially unsettling truths.