Ureteral Stones Are Not Something You Want Twice—or Even Once

Pain so intense it provokes nausea and vomiting. A constant urge to urinate. Mild pain when you manage to pee.

Even more discomfort can result if there is an underlying issue that obstructs urine flow, because fluid can back up and cause a kidney to swell.

This is the potential scenario for someone who develops ureteral stones.

Stones can form in the kidneys over time, especially when concentrations of calcium and oxalate increase.

"Typically, a stone will randomly release from the kidney and start to travel down the ureter, the little, narrow tube that connects the kidney to the bladder," said Noah Canvasser, M.D., an assistant professor in the department of urologic surgery at the University of California, Davis. "This is when it becomes a ureteral stone."

Stones are becoming more common, he added, noting the incidence of kidney stones over the past 12 months—the number of people who developed a stone of some kind—is about 2 percent.

According to Seth Bechis, M.D., an associate professor of urology at the University of California, San Diego, once someone has had a stone, there's a 50 percent chance the person will develop another symptomatic stone in the next eight years. Historically, men have had a higher incidence of stones than women, but women are now probably equal to or surpassing men in this area, which Bechis attributes to a change in how stones have been documented.

Symptoms of stones

While virtually all stones originate in the kidneys, they might not present symptoms until they enter the ureter, Bechis said.

"I think, more likely these symptomatic stones are going to be ureteral," he said.

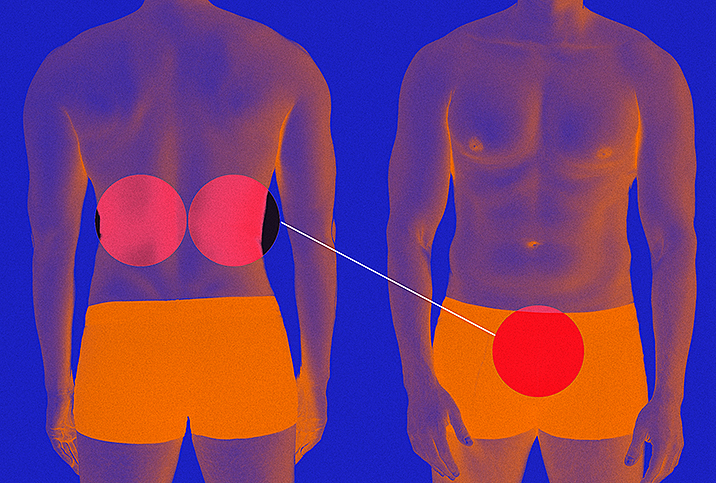

Canvasser explained that flank pain, when one side of the abdomen hurts, is the most common symptom.

"While many patients say the stone is the worst pain ever, I do see some patients with more mild symptoms," he added. "The pain typically does not correlate well with the size of the stone."

Bechis said the flank pain can occur in intervals and feel sharp, like someone is sporadically stabbing you in the back with a knife, but ureteral stones can conversely produce a dull ache. Nausea and vomiting are commonly associated with the severe pain the stones can cause.

"So it's almost like someone hits you in the back and then you double over because you got punched in the belly, and it can be very excruciating," Bechis said. "And then, as the stone moves down the ureter, sometimes the pain pattern shifts and it can [be felt] more in your abdomen—your lower abdomen around the beltline—sometimes even radiating to the groin."

When a stone moves down the ureter and approaches the bladder, the pain can relocate to the lower, ventral (front) side of the body, and when the stone nears the bladder, it can cause what Canvasser called "urinary urgency."

"You feel like you have to go, but nothing comes out," he added, and when you can urinate, pain often accompanies it, much like with a bladder infection.

Someone experiencing severe pain and fever, or anyone who cannot keep fluids down because they start to throw up constantly, needs emergency care, Bechis said.

Diagnosis of stones

Bechis said "an index of suspicion" is key to a ureteral stone diagnosis. What he means is that doctors look for several specific indexes, from the onset of sharp pain, which may or may not be related to urinary issues, to nausea to vomiting.

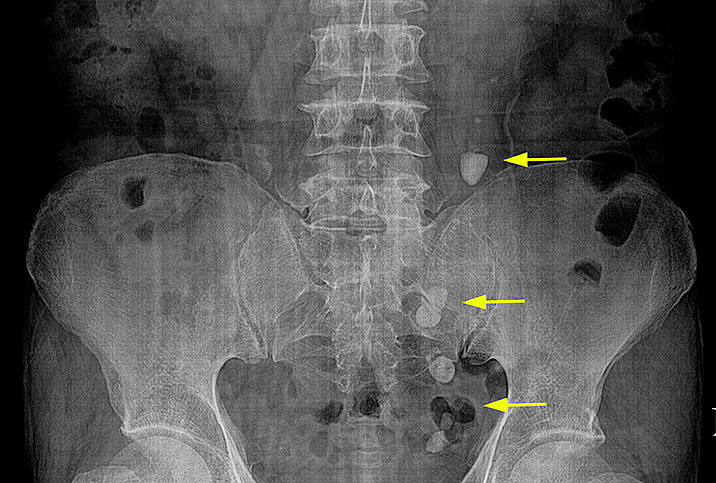

If a patient goes to the ER, a doctor who suspects stones often does some form of imaging, such as a CT scan or an ultrasound of the kidney with an X-ray, to confirm their presence, Bechis said. A CT (computed tomography) scan can help pinpoint the location of stones and is useful in determining the exact size and shape. Bechis also mentioned the availability of low-dose CT scans that emit low levels of radiation.

Canvasser said imaging via CT scans is the most common method for diagnosing ureteral stones.

Treatment of stones

Anatomical factors can keep a stone from passing. One example is someone who has a narrowing in the ureter, which can cause a stone to get lodged in there until it is surgically removed, Bechis said.

The size of a stone typically plays a role in whether it will pass on its own or require treatment.

Depending on where the stone is, a 5-millimeter stone has about a 50 percent chance of passing in six weeks, while a 2-millimeter stone probably has an 80 percent chance. An 8-millimeter stone likely has a 25 percent chance, Bechis said, based on rough calculations he and his colleagues use. These estimates, along with an explanation of treatment options, can be used to counsel patients, who then can decide if they want to wait to see if the stones pass on their own accord.

According to Canvasser, stones less than 5 or 6 millimeters have a decent chance of passing without the use of technology, so doctors typically allot four to six weeks following diagnosis for that to happen, if the patient isn't experiencing discomfort.

Bechis said if patients drink lots of fluids, take medication for the pain and perhaps add a drug such as tamsulosin (brand name Flomax) that can relax muscles and make urination easier, someone is better poised to pass a stone without invasive intervention.

Canvasser indicated urologic surgeons tend to try one of two approaches when intervention is needed.

"The more common way is called ureteroscopy, where we insert a small camera through the urethra, into the bladder and then into the ureter to break up the stone with a laser and extract the pieces. This is the more definitive but also more invasive option," he explained. "The other way is called shockwave lithotripsy, where shockwaves are generated outside the body via a machine and directed to the location of the stone. This is less invasive and also has a lower success rate. But when it works, the stones break up into small pieces that are then easier to pass."

Bechis said most urologists would likely choose shockwave therapy before other methods if deciding for themselves, but he also acknowledged the disadvantage: it probably works only 70 percent of the time.

"If you have a larger stone and it doesn't break into small pieces, but it breaks into, you know, a couple large pieces and a few small pieces, you may experience pain while those are passing," he said, adding that ureteroscopy is probably about 90 percent effective, because it allows the surgeon to visualize the stone during the entire operation and methodically remove the shattered pieces.

"The most invasive technique is called PCNL, or percutaneous nephrolithotomy, and that's generally reserved for larger stones that are in the kidney, although not always," Bechis added.

Using that approach, a surgeon creates a small hole—about 0.5 centimeters to 1 centimeter in diameter—in the back of the kidney and then inserts a vacuum of sorts to break up the stone and suck out the pieces.

"You're putting a needle through the back into the kidney, so there [are] more risks involved in potentially injuring other structures or having some complications," Bechis said.

Ureteral stones and sexual function

Bechis said pain produced by stones can be debilitating, which can cause people to lose interest in activities they would otherwise enjoy, sex included. Discomfort and symptoms can interfere with someone's sex drive.

Fortunately, ureteral stones don't have a direct impact on sexual function over the long term, Bechis said. He also said stones don't really affect hormone levels.

Canvasser highlighted how the stress that can come with forming and then trying to pass a stone or with surgery to remove one can impact all aspects of life: eating, sleeping, working and even desire for or diminished experience of sexual pleasure.

"This is why when you see a kidney stone specialist, we really focus on prevention," he explained.

Prevention of stones

Given the frequency with which stones can recur, patients who have passed stones or had them removed also have reason to focus on preventing future stone formation.

"I think patients are pretty motivated to want to do that, because once you've had a painful attack, nobody ever wants another one," Bechis said.

Assessments that can aid in prevention include metabolic evaluations, 24-hour urine collections and even newer genetic tests that can detect a condition called primary hyperoxaluria, a disorder affecting the kidneys that predisposes people to a buildup of oxalate capable of contributing to ureteral stones.

Hydration is also paramount to preventing stones.

"I think the biggest thing is that most people do not drink enough water on a daily basis, which is the best prevention strategy for stones and also just so important for general health," said Canvasser, who personally likes to consume water just before meals to help ensure adequate intake, which is a strategy patients have also used with preventive success.