The Ballad of the Queer 'Late-Bloomer'

If you spend enough time in the queerer corners of the internet, you'll find 'coming out' stories all the time, not just on October 11. Some are hilarious, some are heartbreaking, and all are part of an illustrious queer rite of passage.

You'll also learn quickly that for some, coming out is fraught for reasons unrelated to how it will be received by loved ones. There are dozens of posts and articles from people in their 20s and 30s bemoaning their status as a 'late bloomer' because they didn't come into their queerness before adulthood.

It's clear that many of us feel like coming out is akin to a developmental milestone, like puberty, that's supposed to happen to everyone by high school. This notion is patently false and yet it still generates a great deal of shame and confusion for people of all ages. Where did it even come from?

Coming back from comphet

Sadly, 'late-bloomer syndrome' is something I'm intimately familiar with. When I first came out to my friends and family as bisexual at age 23, I felt virtually no shame about my attraction to women and nonbinary people, which I'd been vaguely aware of for several years at that point.

However, I did feel tons of shame about how long it took me to call this attraction what it was: queerness. Almost all of the coming out stories I'd ever been shown were about adolescents, like Canadian teen soap "Degrassi: The Next Generation," or "Skins" (U.K.). I figured I'd done it all wrong and had to catch up somehow.

Unsurprisingly, nearly everyone who wanted to speak with me on this topic is bisexual, pansexual, or queer. Compulsory heterosexuality, or comphet, the social norm under which we're all assumed to be straight unless proven otherwise, has really done a number on this cohort. Unlearning that mindset—and the pain that it caused—is a time-consuming endeavor.

When stubborn myths steal time

This has undoubtedly been the case for Rhiannon Rees. Now 29, living in Johannesburg, Rees started to notice she was "different" in her early teens. Her peers seemed focused on the so-called opposite sex, which wasn't the case for Rees.

"At the time, I didn't have the tools or language for it, I just knew I wasn't your typical teenage girl fawning over only boys," said Rees, who first came out as queer two years ago. As she was growing up in the aughts, platitudes like "gay is okay!" were becoming common. But she quickly discovered that her loved ones held her to a different standard.

"When I did speak to my mum and some close friends as a teen about being attracted to other genders, it was constantly dismissed as a phase," said Rees. "Fifteen years later, I think it's safe to say it wasn't."

Rees came out after a series of affirming occurrences, including finding a good therapist and writing a dissertation on queer entrepreneurship. She also dove deep into articles, tweets and TikToks about gender and sexuality, and found that she was part of a vibrant and diverse community.

With newfound emotional and informational support, Rees gradually acquired the language to describe her attractions in nuanced ways and learned that she was not the only one in the world with those feelings. She just wished it could have happened sooner.

Bloom or break

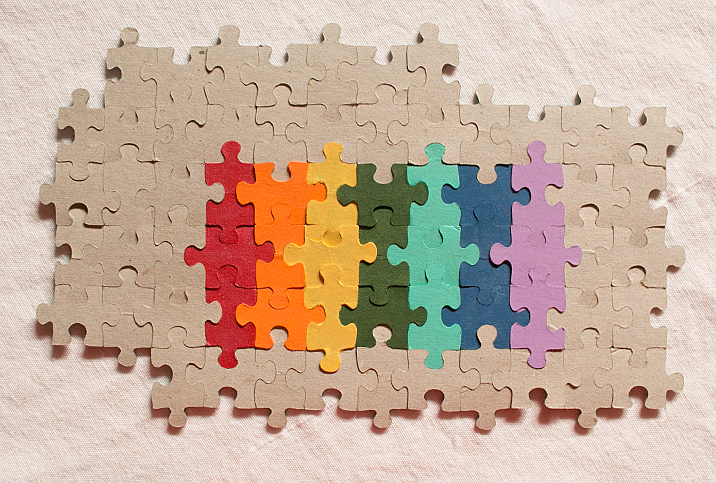

Misconceptions about bisexuality, like thinking it's a phase, or that it's performative, aren't exactly benign. Although studies show bi+ people make up more than half of all those under the LGBTQIA+ umbrella, their experiences are marginalized by straight cis people and monosexual queers alike, which can be profoundly alienating, or even dangerous.

Bi and pansexual people, especially women, experience elevated rates of intimate partner violence, substance abuse, mood disorders, and suicide compared to people who are straight or gay. They're also more prone to chronic illnesses, including asthma, breast cancer and heart disease.

Experts connect these disparities to the decreased likelihood of a bisexual person being "out" due to rampant biphobia, which can cause the buildup of toxic stress. Being gaslit about your existence can literally break your heart. It's the type of wound that takes quite a long time to heal.

In a culture that's been beating the "born this way" drum for decades, it makes perfect sense that bi+ people are so well represented among the late bloomers. We need extra time to cut through the nonsense and connect with the feelings we were denied for so long. We need time to find our pride.

Looking back

Everyone I spoke with seemed to have a "better late than never" attitude about their situation. Even still, some find it hard not to wonder what might have been.

"There is a high possibility that I could have avoided what turned out to be an abusive relationship," said Bob O'Boyle, 40, who is asexual and nonbinary. He discovered his asexuality and genderqueerness in his mid-30s, after leaving a spouse that subjected him to rape by coercion.

Meanwhile, Jermany Brown, a pansexual woman, feels self-conscious about her sexual inexperience with certain types of bodies. "I definitely wish I'd have known earlier," said Brown, 28. "I feel like I missed out on a lot. I'm still learning my way around a woman's body and that intimidates me at times."

'I didn't start feeling like myself until I stood in my truth, because it allowed me to be honest in other areas of my life.'

Brown came out as bisexual at 22, after meeting a woman and entering into a relationship. She'd been attracted to non-men throughout her life but "never explored," because of compulsory heterosexuality. Aside from missing out on having more honest and fulfilling relationships, Brown feels the loss of a prime opportunity for personal development.

"I think if I had discovered my queerness at a younger age, I would have become more confident in who I am sooner," she said. "I didn't start feeling like myself until I stood in my truth, because it allowed me to be honest in other areas of my life."

For Rees, being told so often that her feelings were a phase did real damage, saddling her with the mammoth task of unlearning her internalized queerphobia. "I wish I'd had the space to question, explore, discover, and indulge my sexuality as a teen," she said. "I feel like if I had, I could have skipped a lot of the depression and anxiety that comes with an identity crisis."

The journey isn't quite over for Rees, who has come out to her internet community and several IRL friends but not to her parents, with whom she doesn't feel all that much pressure to discuss her identity. When the time is right, she will. It's a reminder that for many queer folks, coming out isn't a grand singular event, but something that happens over and over, in big online announcements and quiet conversations, over the course of many years.