How Ketamine Therapy Offers Hope For Treatment-Resistant Mental Illness

In March of 2020, the FDA approved the first truly novel drug treatment for depression in decades—but the drug itself wasn't new.

In fact, ketamine had lived many lives before—treating soldiers on the battlefields of Vietnam, a staple in veterinary offices and extremely popular over the past three decades at raves and dance parties. And now it's found its way onto the proverbial therapist's couch.

Ketamine is the first drug of the so-called psychedelic therapy movement to receive approval all across the U.S. and Europe for treatment-resistant mental illnesses, including PTSD, depression and anxiety. In the past year, new ketamine clinics and telehealth startups have popped up all across American and European cities, promising relief to patients who have otherwise lost hope in traditional antidepressant treatments.

So, what is ketamine therapy really and how does it work? And what's it like to score Special K from your psychiatrist instead of some shady guy in the bathroom of a nightclub?

Taking a closer look at ketamine

Many people know ketamine as a recreational drug—often called K, Special K or Ket. You may also have heard ketamine referred to as "horse- or cat tranquilizer."

The latter designation is only half-accurate—while ketamine is used in veterinary medicine, the drug has been approved as a human anesthetic since 1970. It saw heavy use during the Vietnam War, offering medics a comparatively safe way to administer anesthesia on the battlefield.

Recreational use of ketamine really took off, though, in the mid-80s and 90s, particularly in dance music subcultures. Users snorted, injected, mixed it into drinks and rolled it into cigarettes to experience the unique trip Special K can take you on.

Though it produces some psychedelic effects, ketamine is actually classified as a dissociative anesthetic: "Dissociative" because it can produce a detached sense from one's own body and senses; "anesthetic" because it dulls physical sensations, including pain.

Compared to psychedelics like LSD or psilocybin, the duration of a ketamine trip is relatively short, lasting around 30 minutes up to two hours.

In higher doses, ketamine can produce hallucinations and out-of-body experiences. The slang expression for this is "falling into a K-hole." For most people, this may be enjoyable, a feeling of floating above your body, even melting into your surroundings. For others, though, the K-hole experience can cause confusion, paranoia, panic and anxiety.

Ketamine in the lab

In 1999, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) placed ketamine into schedule III of the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) in an attempt to curb recreational abuse of the drug. But not too long after ketamine became a controlled substance, researchers first began to take notice of the drug's apparent ability to rapidly alleviate depression.

Ketamine is often lumped in with the novel "psychedelic therapies." That is, psychoactive drugs like MDMA (Ecstasy/Molly), psilocybin (magic mushrooms) and ketamine previously associated with recreational use, are now used and studied in clinical settings to treat everything from PTSD to anxiety disorders to drug addiction.

Emily Robison, a professor of psychopharmacology at the University of Bristol, says that most of the research shows these drugs work really well for treating depression and other mental illnesses. Scientists are just not quite sure how it works the way it does.

"Essentially you've got this group of drugs that are called psychedelics, dissociatives, whatever you want to call them, and these seem to be able to have very profound, rapid effects on mental health disorders," Robinson said. "Nobody has a clue how they do that."

Theories abound, of course. In her research, Robinson studies the possibility that ketamine and other psychedelics may impact metaplasticity—a theory that these drugs are "prime" brains for new learning, allowing novel positive thought patterns to replace older negative ones.

"I like to think of it like going back to childhood, where you're much more explorative. You haven't learned everything yet, so you're happy to explore and try stuff out. Whereas when we get older our brains tend to get narrower in terms of how they behave," Robinson explained.

Ketamine vs. SSRIs

Ketamine wouldn't be the first (or second, or third) drug prescribed to patients suffering from symptoms of mental illness, according to Dr. Tiago Reis Marques, the founder of Pasithea Therapeutics, a biotech company based in Miami, Florida and the UK that researches new drug treatments—including ketamine—for mental health disorders.

"Right now, ketamine therapy is only recommended for patients who haven't found relief in more established mental health drugs such as SSRIs," Marques said. "This is not considered to be the first treatment [someone] is going to receive. This is a treatment for a patient who is not responding to their normal treatment."

"Around 30 percent of individuals with depression don't respond to conventional antidepressant medications," Marques added.

PTSD is a similar story. There are only two SSRIs that have been approved for treating PTSD and so the list of pharmaceutical options runs out pretty quick. For many, there haven't been many avenues left after traditional drug treatments have been exhausted.

Until quite recently.

'This is not considered to be the first treatment [someone] is going to receive. This is a treatment for a patient who is not responding to their normal treatment.'

"The results from clinical trials and treatments have been very promising," Marques said, "with the majority of individuals with treatment-resistant depression showing some improvement in symptoms from ketamine therapy.

"Up to 70 percent of treatment-resistant depression ends up responding to these medications," Marques continued. "This is really remarkable, this is really a success story"

Marques added that fewer studies have been done on ketamine and PTSD but the available evidence is similarly promising. Research indicates more than 50 percent of patients with treatment-resistant PTSD find some relief in ketamine.

"Ketamine is hugely different from SSRIs," Robinson said. "The two drugs are dissimilar in their chemical makeup, of course, but they also differ in how quickly they alleviate symptoms. SSRIs can take a couple of weeks to a month or more to take effect—during which time many patients feel worse before they start to feel better."

But ketamine appears to work almost right away. Moreover, a single dose appears to work for a longer period of time, whereas SSRIs typically require taking a pill every day.

"There's something about these drugs that is just so different," Robinson explained. "Rather than taking a pill every day and taking a long time to work, you feel better straight away and you stay well for several days, possibly even several weeks."

What does therapy look like?

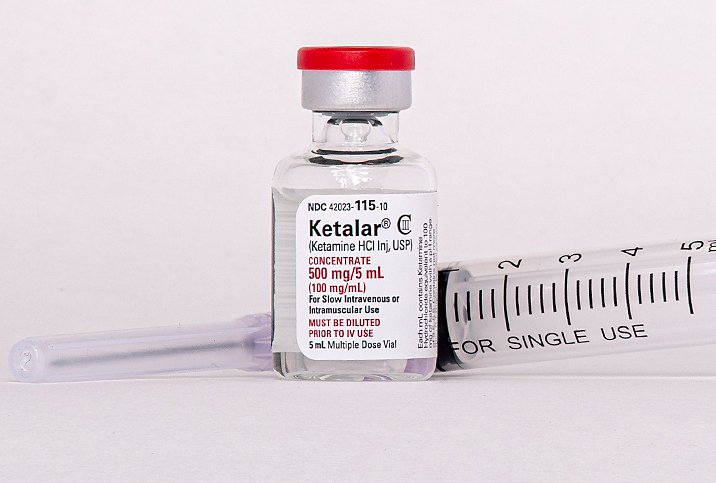

Pasithea recently launched a ketamine clinic in the UK, as well as mobile ketamine clinics in several major cities across the United States. Marques described the typical procedure for a potential patient seeking ketamine therapy at one of his clinics.

"The preliminary stage begins with a psychiatric evaluation, Marques said. "Patients will be interviewed on their symptoms, past history of treatments, as well as any risk factors that might make ketamine treatment inadvisable. Eligible patients are then debriefed on what to expect before their first session."

Marques made it clear that ketamine therapy is not a guided trip or psychedelic psychotherapy session. While medical personnel are on-hand to calm a distressed patient or issue emergency care, most patients lie in silence for the duration of the treatment.

In fact, while patients are informed that they may feel the effects of ketamine—"disassociation, feeling that the world is strange, changing perception of time and space" as well as sedation—the dosage used typically isn't enough to make most patients "trip." Ketamine is generally prescribed at around 1-2 mg per kg of body weight.

"The dose that people take for recreational use is much higher than the dose we are giving them," Marques said. "So the patients don't feel the high that is normally associated with ketamine when used recreationally"

In the UK, these sessions are conducted in a dedicated clinic, but in the U.S., Pasithea sends one of their doctors to the individual's home, armed with blood pressure monitors, "rescue medication" and a ketamine IV.

Ketamine is injected intravenously over the duration of 40 minutes, during which patients can choose to lie down, keep their eyes open or closed, wear an eye mask or listen to music.

For Pasithea patients, treatment consists of six of these sessions over the course of two to three weeks.

"This is in order to reduce the relapse of symptoms," Marques explained. "Improvements in symptoms can diminish over time, so several sessions over a short period are usually recommended."

Side effects and risks

Marques and Robinson agreed that ketamine therapy thus far appears to be a very safe treatment with few side effects. But like any drug, ketamine comes with some degree of risk.

Because of its long history of recreational use, the possibility of addiction might be an obvious concern for many patients. But as of right now, Dr. Marques said, that doesn't appear to be a problem.

"There's never been a case reported in the literature of a patient who received ketamine for the treatment of a psychiatric disorder who [afterward] started using ketamine recreationally," Marques stated.

During the treatment itself, some patients might find ketamine's dissociative effects unsettling or experience unpleasant side effects like nausea, increased heart rate and/or blood pressure. And while the latter may not be dangerous for healthy individuals, it could pose some risk to those with heart problems.

"Pre-screening risk factors is critical when providing access to ketamine," Marques said, "as is the presence of medical personnel during treatment." He also expressed some reservations toward companies conducting ketamine therapy wholly over remote telehealth services, mailing their patients ketamine doses in oral form.

Robinson offered the warning that all the research carried out on so-called psychedelic therapy is very much in its early stages. Some of the excitement and hype around these novel treatments should be balanced with a degree of skepticism and caution—though results thus far have been very promising.