Rectal Spacers Create a Barrier Against Radiation Treatment

A significant concern with radiation treatment for prostate cancer is the proximity of the prostate gland to the rectum. When external beam radiation is used to kill the cancer cells in the prostate, there's a risk that the radiation could damage the rectum.

This damage could result in a host of bowel symptoms, such as rectal bleeding, fecal incontinence and diarrhea.

"Usually there's a fatty tissue in between the [prostate and rectum], but the amount of space in between it could be centimeters or millimeters," said Daniel Lee, M.D., an assistant professor of urologic oncology in the surgery department at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. "The biggest way to relate this to the person on the street is when you have your finger up there, directly from the rectal wall, you can feel the prostate."

The radiation issue has caused problems for prostate cancer patients and others who have needed radiation treatment near the rectum. The treatment can be lifesaving, destroying cancer cells while leaving healthy tissue alone, but potentially life-altering.

Recently, patients and their medical teams were given an ally in the fight to keep radiation beams away from the rectum: rectal spacers.

What is a rectal spacer?

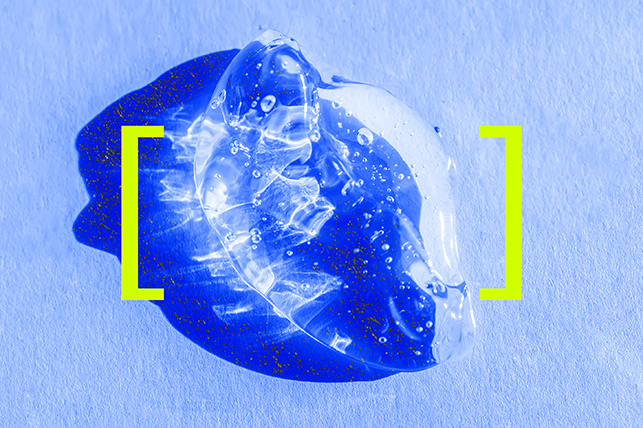

Rectal spacers give radiation-treatment patients a chance to protect their rectum while doses of radiation are delivered. One such tool is a hydrogel spacer, a soft gel material that creates space between the prostate and rectum. It is placed before radiation treatment begins and stays in place for the duration.

"Any amount of space or distance that you can get from [the rectum] is exceedingly helpful," Lee said.

The space the hydrogel creates provides an exponential improvement in terms of decreasing the risk of the rectum's exposure to radiation, Lee explained. This allows the radiation oncologist to aim the beams more safely at the prostate, ensuring that they kill all the cancer cells in the gland while decreasing the risk of potential complications.

The use of a hydrogel spacer can result in significantly fewer complications and less irritation, Lee said. Doctors who have used a spacer indicate they are safe to deliver to the necessary location.

Only a couple of such devices exist. SpaceOAR is a commonly used rectal spacer brand and is currently available in the United States. Barrigel, another brand of rectal spacer, was cleared for use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2022.

Clinical trials have shown fewer bowel, urinary and sexual complications in men who had the spacer compared to control groups.

How it works

Andrew Elson, M.D., a radiation oncologist at Mary Bird Perkins Cancer Center in Hammond, Louisiana, is familiar with SpaceOAR. He said he's used it with about 150 patients since 2018.

"It's been very successful," Elson said. "Most of the major academic centers have adopted it for use. A lot of private clinics use it, too."

Practitioners don't know the exact ingredients because it's proprietary, he said. It comes as a kit, and the kit has two vials of liquid. One vial is polyethylene glycol; the other vial is an unknown chemical accelerant. He added that about 90 percent of the SpaceOAR hydrogel is water.

Barrigel, on the other hand, uses hyaluronic acid but serves the same purpose as SpaceOAR.

"We basically assemble the two vials into a Y-shaped tube, and then you inject both liquids, and the liquids mix in the nozzle of the tube," Elson explained. "When they're mixing, as long as they're flowing, they remain a liquid. But then when they stop moving, they turn into a gel."

The goal is to place the gel between the prostate and the rectum. Once it transitions from a liquid state to a gel state, it stays there, and the accelerant creates a matrix out of the polyethylene glycol.

What the procedure entails

"It's a relatively simple procedure," Elson explained. "At the beginning, they used to do it in the operating room where [patients] were completely under anesthesia. In more recent years, we've actually figured out you can do it as an outpatient."

Elson uses lidocaine, a local anesthetic, to numb the area, after which the patient sits for about 45 minutes. Once they get set up in the procedure room, the procedure takes about 20 minutes. Elson uses ultrasound to guide the needle and ensure the gel is injected into the correct location. Once the needle is in the right spot, injecting the spacer liquid takes about 20 seconds.

Patients need to stay under observation for about 20 minutes to make sure they feel well and their vital signs stay steady. The total time the patient is at the building for the procedure is about two hours.

"Usually we recommend people have somebody come with them when they do the procedures so they can drive them home, because we do give them a mild sedative," Elson said. "Most people have a little bit of pressure after we put it in for a couple minutes. It feels like pressure by the rectum and then it usually just goes away after a few minutes. Some people are a little bit nervous about it. Most people do fine with it and don't have any major issues."

The hydrogel spacer remains in place during radiation treatment, which generally lasts for five to eight weeks. It remains between the prostate and rectum for about three months before it begins to slowly break down. The gel gets absorbed by the body and, ultimately, excreted through the patient's urine after about six months.

Complications and costs

Implantation of the spacer is generally a safe procedure that carries minimal risks. Like any procedure, however, there's always a theoretical risk. One potential negative outcome of the hydrogel spacer placement is that the gel could go through the rectum.

"Even if it does, most of the time, that's not really a huge problem," Elson said. "But if too much of it gets into the rectal wall, that could cause an ulcer or some other problem. I think that's been reported a few times, but it's very, very rare."

Even without using a hydrogel spacer, serious complications from prostate radiation treatment are rare, according to Elson.

"Basically, the risk of it with the spacer is effectively zero," he said.

The biggest hurdle Elson has encountered has been insurance coverage. Some carriers do not pay for the kits.

Elson finds that a vast majority of patients with prostate cancer who seek radiation treatment prefer to use hydrogel if it's covered by their insurance. The SpaceOAR kit sells for $2,900. Additional fees for the necessary clinical equipment bring the out-of-pocket total to about $3,500.

However, even if the patient's insurance does not cover it and they opt not to use a spacer, Elson said the risk of side effects and complications is very low due to advancements in radiation therapy.

Elson uses intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), a form of 3D-CRT—three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy—a widely used type of external beam radiation therapy for prostate cancer. This involves a computer-assisted machine moving around the patient as it delivers radiation, working the dose away from the rectum.

"If we can get the spacer, it just helps protect the rectum a little bit more," he said.