Contraceptives Could Still Be Effective With Up to 92% Fewer Hormones

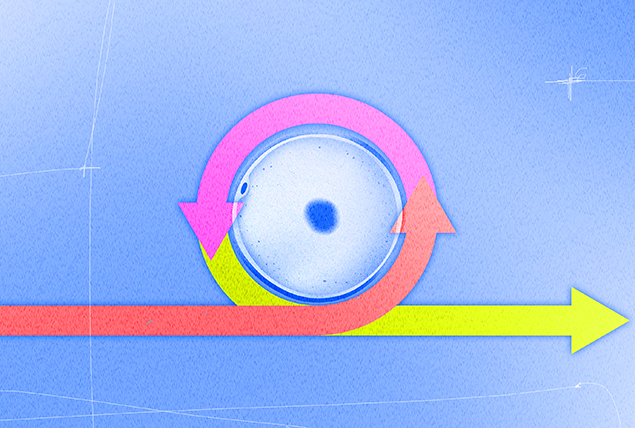

A new study suggests reducing the hormone dosage in different types of birth control might be possible. These forms of birth control include contraceptive pills, patches, intrauterine devices (IUDs), rings and implants to help reduce unwanted effects without compromising effectiveness.

What does the study suggest about reducing hormones in birth control?

More than 65 percent of women ages 15 to 49 in the United States use hormonal contraceptives such as birth control pills, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Besides preventing unintended pregnancy, oral contraceptive medications and devices can also help manage conditions such as painful periods, heavy periods, hormonal imbalances and endometriosis. But like any drug, they can have side effects.

Researchers from the Philippines, Denmark, the Republic of Korea and the U.S. used mathematical models to test the impact of varying levels of exogenous hormones in the new study, published in the journal PLOS Computational Biology.

All bodies are different and there is no one-size-fits-all contraception method.

Their findings indicate the hormones in estrogen-only methods could be reduced by up to 92 percent and still prevent pregnancy, while those in progesterone-only versions could be lowered by 43 percent. Dosages in combination pills or methods that contain estrogen and progesterone could be reduced even further.

How did the hormonal birth control study work?

Researchers evaluated the hormone levels in 23 women ages 20 to 34 with regular menstrual cycles lasting 25 to 35 days.

Besides dosage, researchers examined the effects of timing. They aimed to determine what doses of exogenous hormones were needed to prevent pregnancy. They also wanted to know if administering doses at specific phases in the menstrual cycle might affect results.

The researchers used two different models to assess the effect of hormones on the ovaries and pituitary gland, respectively. The ovaries and the pituitary gland produce and regulate hormones.

The results suggest administering estrogen and progesterone at particular times of the month might be more efficient and effective than giving one continuous, steady dose throughout.

Timing matters because the menstrual cycle is a series of hormonal changes in the body that trigger a predictable set of events in a specific order, according to Sarah Diemert, W.H.N.P., a Denver-based women's health nurse practitioner and the director of medical standards integration and evaluation at Planned Parenthood Federation of America.

"There are peaks and valleys of different hormone levels that are responsible for triggering the events within the cycle, such as ovulation and menstruation, or when you bleed," she said.

The cycle consists of four phases, according to Cleveland Clinic:

- Menses. The uterine lining sheds, resulting in a period. This phase, which starts on day one, typically lasts five days.

- Follicular.Next, the pituitary gland releases follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), which prompts follicles—the fluid-filled sacs that contain immature eggs—to develop in the ovaries. Usually, one follicle matures into an egg ready for fertilization. The follicular phase lasts from about day six to 14.

- Ovulation. In the first part of the luteal phase, the ovaries release the mature egg, which travels to the fallopian tubes.

- Luteal. The follicle that released the mature egg in ovulation morphs into a small cyst called the corpus luteum, which secretes progesterone and estrogen to thicken the uterine lining in preparation for pregnancy. If you don't become pregnant, the corpus luteum decays and becomes a corpus albicans.

Hormonal contraceptives employ synthetic versions of the two most important hormones—estrogen and progesterone—to prevent ovulation, Diemert said. They can also thicken the cervical mucus to inhibit sperm from reaching an egg and thin the uterine lining to stop an implanted egg from attaching.

The study authors noted that synthetic hormones were most useful during the mid-follicular stage. Reducing the dose at cycle phases could minimize the overall amount administered while preventing ovulation.

Brenda Lyn A. Gavina, a Ph.D. student and mathematician at the University of the Philippines Diliman and Aurelio A. de los Reyes, Ph.D., an assistant professor at the Institute of Mathematics, University of the Philippines Diliman, in Quezon City, were two of the study's lead researchers.

"The model we developed in this study serves as a first step in using mathematical modeling to explore the transition to a contraceptive state," they wrote in an email interview. "When more data become available, the current model can be coupled with a pharmacokinetics model to obtain patient-specific minimizing dosing schemes."

What are the potential birth control side effects and health benefits?

About half of users have no complaints, according to Melanie Bone, M.D., an OB-GYN based in West Palm Beach, Florida, and the U.S. medical director for Daye, a gynecological health platform. But an estimated 60 percent of Americans discontinue hormonal contraceptives after six months due to side effects.

"Usually, those side effects resolve by the third month as your body adjusts to the hormones," said Cristin Hackel, M.S.N., W.H.N.P., a women's health nurse practitioner in Bethesda, Maryland, who works at Nurx, a telemedicine company. "But they don't always resolve, which means that it's likely not the right dose or method for that person."

Common examples of the side effects of birth control, according to Alyssa Dweck, M.D., a gynecologist in Westchester County, New York, and a sexual health and reproductive expert for Intimina, a brand of products focused on women's intimate health, include the following:

- Breakthrough bleeding/spotting

- Breast tenderness

- Bloating and fluid retention

- Nausea

- Headaches

- Acne

- Abdominal pain

- Mood swings

- Weight gain

- Dizziness

- Fatigue

Less commonly, Dweck said hormonal contraceptives can potentially increase the risk of the following conditions:

- Blood clotting, including pulmonary embolism

- Stroke

- Heart attack

- Gallstones

- High blood pressure

Dweck said different methods have distinct effects depending on the dosage, continuous versus cyclical administration and the type of artificial hormone used. Everyone's experience is different.

While finding ways to minimize unwanted effects is essential, according to Bone, so is recognizing hormonal contraceptives' many benefits.

Beyond pregnancy prevention, Bone and Dweck said these medications can help to:

- Clear up acne

- Alleviate period pain

- Regulate menstruation

- Reduce endometriosis symptoms

- Diminish uterine and ovarian cancer risk

- Improve PMS symptoms

- Reduce excess hair growth associated with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)

- Lower the risk of ovarian cysts

Dweck said lowering the hormone dosage could reduce the incidence of side effects, both nuisance and significant.

"Less hormones in contraceptives may lower the already really rare risks associated with hormonal birth control, such as blood clot, stroke," Diemert said.

Experts said it's unclear how that might impact menstrual flow or the medications' potential benefits.

"It is not yet known if reducing the dose of hormonal contraception will affect the associated side benefits," Bone said. "There is evidence that low-dose pills do help with a lot of these issues by the very fact that they stop ovulation."

What could this study on hormonal contraceptives mean for you?

Experts said the study's findings are promising. But, as the study authors acknowledged, they're not at the point of clinical use. More research is needed.

The study's results are not directly translatable to patients, Gavina and de los Reyes wrote, but the principles are. Their hope is that the results help clinicians identify the best, patient-specific dose and treatment schedules to achieve the most effective, efficient and safe use. Also, new formulations influenced by the findings could be tested in clinical trials.

'Some people will experience side effects from a particular form of contraception. Others won't.'

Dweck and other experts pointed out that previous research has prompted multiple improvements. This study could lay the groundwork for more.

"The doses of hormones used in birth control have continued to get lower over time. We no longer use the doses our mothers or grandmothers used, and the benefits of improved safety and side effects are evident," Hackel said.

Low-dose options are few, she added, saying more such choices would be welcome.

"If more studies can show that lower doses are effective in preventing pregnancy as well as managing the other symptoms that birth control is used for, they will likely be greatly desired," Hackel said, adding that it could be challenging to implement the researchers' theory in reality.

"Diabetics use glucose monitors and insulin pumps implanted in their skin to manage their glucose and insulin levels. This is what I imagine as a birth control method if a release of hormones to prevent ovulation is based on the levels of other hormones in the body. It's hard to imagine that being very popular for most hormonal contraception users," she said.

Since cycles can vary in length from one month and person to another, ensuring everyone took them at precisely the right time could be challenging.

"However, I look forward to seeing what options are created, especially if the hormonal doses can continue to be lowered to decrease risks and side effects for everyone," Hackel said.

The bottom line

All bodies are different, experts reiterated, and there is no one-size-fits-all contraception method. That's why it's important to talk with a healthcare provider to find the right birth control fit.

Some people will experience side effects from a particular form of contraception. Others won't, Bone pointed out. That's why patients need to discuss any potential side effects with a healthcare provider when trying to find the best contraception for them.

"It's best to come prepared with your health and contraceptive history to an OB-GYN appointment so you can make an educated choice in partnership with your physician," Bone said.