2 Blood Markers May Build a Better Prostate Cancer Risk-Detection Tool

While prostate cancer remains the second most common type of cancer in men in the United States, trailing only skin cancer, tremendous strides have been made in screening.

The most prevalent first-line test to detect prostate cancer, the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test, has been used to diagnose countless high-risk cancers in an early stage, helping millions of men around the world live longer, better-quality lives.

However, evolving guidance from the American Urological Association (AUA) on prostate cancer screening can sometimes seem confusing.

That's because urologists have stepped back in recent years from what some saw as the overzealous use of PSA tests and their results. Specifically, positive tests were sometimes overinterpreted to indicate the need for a biopsy or potential treatment, even for low-grade cancers. These interventions sometimes proved to be unnecessary and even traumatic.

Now, a new study in the United Kingdom claims to demonstrate how using an algorithm incorporating a man's age along with the results of two prostate cancer blood markers can more precisely predict the risk of prostate cancer with a high degree of accuracy.

We'll explain what it all means and whether it may be a game-changer in terms of early prostate cancer detection.

Where we've come from: the PSA test

Prostate-specific antigen is a blood protein produced in all people who have a prostate gland, which is a vital component of the male reproductive system. However, when PSA shows up at higher-than-usual levels, it can indicate the presence of cancerous cells in the prostate. The problem is that elevated PSA levels may also indicate a type of prostate cancer that doesn't require immediate treatment, or could point to completely unrelated issues such as inflammation in the prostate or higher-than-normal testosterone levels.

"The PSA came out in the early 1990s, and it was certainly a game-changer because you could detect early prostate cancer," said Joseph R. Feliciano, M.D., a urologist with the Lehigh Valley Health Network in the Allentown area of Pennsylvania. "Before, patients presented a lot with higher stage and metastatic disease. But then, when PSA came out, it kind of skewed the diagnosis toward the low-grade, low-risk prostate cancer. It led to a lot of overtreatment in men with indolent prostate cancer who then suffer the consequences of treatment, like erectile dysfunction and incontinence."

The latest research

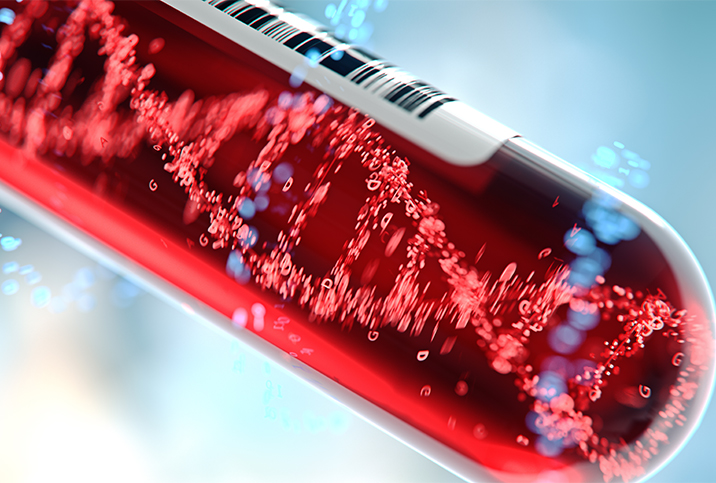

In the U.K. study, published in March 2022, researchers sought to use two blood markers—PSA and a second one called hK2, or human kallikrein peptidase—to more accurately predict prostate cancer risk when fed into an algorithm with the man's age.

"Our study shows a different screening approach could reduce the number of false positives by three-quarters," said the study's lead author, professor Sir Nicholas Wald, of the University College London Institute of Health Informatics, in a press release. "This would make screening for prostate cancer safer and more accurate, reducing overdiagnosis and overtreatment."

The researchers set a risk threshold above which men would be considered "screen positive," and found they could reduce the number of false positives by 75 percent while at the same time retaining the same ability to detect cancer.

The test could be the next game-changer in the field of prostate cancer diagnosis, but it needs more feasibility testing in actual practice, as the researchers know. Assuming the project is successful, however, the widespread adoption of the algorithm created by Wald and his team could be another useful tool for diagnosticians, though whether it replaces the PSA is nowhere near certain. A more likely scenario is it would be used with other diagnostics, including a newer blood marker test called the 4Kscore and another PSA test that synthesizes different PSA values called the prostate health index (PHI).

'Our study shows a different screening approach could reduce the number of false positives by three-quarters.'

"What's been going on now is we say, 'Let's screen smarter.' We know PSA is a good test. It's not a perfect test," said Feliciano, who did not participate in the study. "Here in our practice, when patients come in with an elevated PSA, we repeat the PSA. We don't jump to the biopsy. Patients can then be further risk-stratified with this fancier blood test we use that's called 4K. This study is looking to further risk-stratify who needs further workup, which the next step is the MRI or the biopsy."

It can't be stressed enough that false positives for high-risk cancer, which lead to unnecessary surgery or a biopsy, can be devastating for men. Having the ability to separate low-grade, low-risk cancer—often addressed with active surveillance rather than surgery—from more dangerous kinds can allow a lot of men to live fuller lives with their prostate intact for a longer time.

"Certainly, I think a smarter blood test like the 4K or the PHI, which is what I think they're alluding to, will help in decreasing unnecessary biopsy," Feliciano said. "The 4K looks at precursors of PSA that are more sensitive for clinically significant prostate cancer, Gleason 7 and above. Those are the prostate cancers you want to find and treat, not the indolent ones."

What's next

The research was conducted using blood samples and data from 571 men who died of or with prostate cancer and 2,169 men who'd never been diagnosed. Moving forward, a real-world trial would make sense.

"The next step is to test the feasibility of this approach in practice with a pilot project inviting healthy men for screening," Wald said. "If the project is successful, we believe this approach ought to be considered as part of a national screening program for all men."

At the end of the day, information is the key to giving patients a correct diagnosis and useful advice. Expanding the pool of information from which diagnosticians can draw is invaluable.

The PSA led to the 4Kscore, which led to the PHI, and now, here we are on the brink of practical, real-world testing on Wald's research group's algorithm.

Who knows what the future holds, but for now, if you're a guy of the proper age who has risk factors for prostate cancer, you have to feel pretty good about your healthcare team having the tools it needs to make the right call, with new ones just around the corner.