It Wasn't in My Head; It Was in My Veins

It's a safe bet no guy has ever wanted erectile dysfunction (ED). On any list of the five things guys want least, ED probably makes an appearance. Unfortunately, this desire doesn't change the fact that it's an extremely common issue which affects about 30 million men in the United States.

On top of that, many ED sufferers are hesitant to discuss the disorder. Generally, men don't go to the doctor often anyway, with 65 percent tending to wait as long as possible to see a doctor even when they have symptoms or an injury, according to a Cleveland Clinic survey. Factor in the personal and potentially "embarrassing" nature of ED, and it's a wonder men talk about it at all.

Of course, it's not an issue that should cause embarrassment. It's very common, and the best way to find a solution to the problem is to talk about it. In fact, as more men open up about their struggles with ED, doctors uncover more information about the how and why of ED and can unearth more diverse solutions to the problem.

Take Florida-native Tony (he asked to have his last name withheld for privacy reasons), who is now in his 60s. In his 30s, he first experienced issues with ED and sought a local urologist to help identify any physical problems that could be causing the dysfunction.

"I wasn't shut down," he said, meaning he still could get an erection on occasion, "but it definitely affected me, and I knew it. So I saw a lot of doctors, mainly urologists, and none of them identified a physical problem. They told me it was all in my head. I told them, 'It doesn't really feel like it's in my head.'"

Generally, that's how the story goes. University Hospitals' Nannan Thirumavalavan, M.D., called it the classic textbook teaching. The Cleveland-based urologist said the old school of thought maintained that if a man's morning or nighttime erections were fine, then the cause of his ED must be psychological.

"But that's not really true," he said.

Searching for answers

Tony insisted his issue was not psychological, and doctors offered him a solution: a penile implant. He wasn't keen on that idea.

"It was basically a pump," he said. "That cuts down anything that's natural, and then you have to rely on it. 'Forget it,' I said. I didn't like that idea at all. I told them I'd just learn to live with it, you know?"

He can laugh about it now, but at the time it wasn't a joking matter.

"It was a burden," he said. "If I got in a serious relationship with a woman, I wouldn't say anything about it until we were intimate, and then most of the time they really didn't notice because I'd space out the sex. I'd wait until I was, well, extra horny so I'd know I had all my ammo in there."

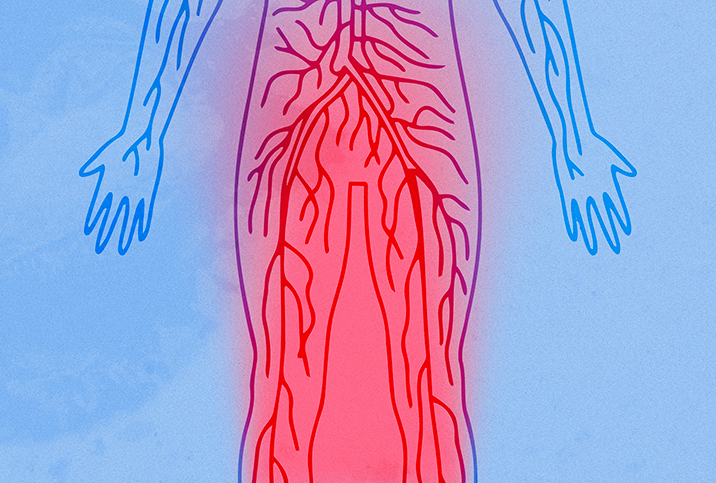

Tony continued to do his own research to try to find answers to why he was experiencing this issue for which doctors, seemingly, couldn't identify a cause. Eventually, Tony believed the problem was a blockage in his veins preventing blood from flowing into his penis. When he brought this theory to doctors, they ran some tests and discovered he was right: There was a blockage.

"They told me there was nothing they could do, though," he continued. "They said the veins down there were too small to fix. Then later, they came out with new technology, and I did see someone again about it. I tried a new procedure about 10 years ago with a doctor at the University of Miami, but he couldn't find any blockage. Of course, I didn't have the scans anymore or I could have shown him exactly where it was. Then they told me the same thing: 'It's all in your head.'"

Finally, hope

Disheartened, Tony grew increasingly desperate for a solution. By this point, he had struggled with ED for about 30 years, and the problem was worsening. Eventually, his search brought him from Florida to Cleveland and the surgical suite of Mehdi Shishehbor, D.O., M.P.H., the president of University Hospitals Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute.

"My area of expertise is vasculogenic erectile dysfunction, which means that you have these blockages preventing blood from getting into the penis to cause an erection," Shishehbor said. "This is the same process that causes heart attacks. This is the same process that causes strokes. It's the same process that causes blockages in the leg and then people lose their leg. It's the same process: atherosclerosis."

Finally, Tony found someone who knew exactly what was causing his problem and could potentially fix it.

"This procedure, you wouldn't even be able to show people you had it," Shishehbor said. "This is something that happens inside your body. It's like getting a heart stent. We basically enter their arteries, just like we would if we were doing a cardiac catheterization. You know, sometimes we go through the wrist, sometimes we go through the groin. We go inside the artery with small wires and a catheter."

'This procedure, you wouldn't even be able to show people you had it.'

From there, he explained the process is effectively the same as putting in a heart stent. Doctors use the same balloons and wires, go into the pelvic artery, take pictures to identify the blockages and then insert a scaffold into the blockages to get the blood flowing to the penis once again.

He said the whole procedure takes about 90 minutes, with another 90 minutes of recovery, and then the patient is free to go.

As for the cause of the blockage, the first question Shishehbor asked Tony was whether he did martial arts or rode a bike. Tony didn't do martial arts but he did ride a bike.

"I wasn't a marathon bike rider or anything, but that's what did it," Tony said.

Tony said his life improved dramatically as a result of the procedure. The long journey, finally, had come to an end, though he was understandably frustrated it had been such a long journey in the first place.

A new way to treat ED

In the end, he found only two doctors, Shishehbor and a doctor in Europe, who specialized in his specific problem.

But Shishehbor is confident this type of surgery could become much more common. The procedure itself isn't uncommon in a broad sense, but the focus needs to be on establishing comprehensive programs that work across departments on patients' erectile dysfunction.

"I'm sure any hospital, if they were to learn it or have somebody that was passionate and was interested, they could figure it out," he said. "It is not just focused on putting in a stent. There may be a lot of programs in the country that can put in a stent, but I don't know how many of them have a comprehensive program around ED where folks are working together in endocrinology, urology and interventional cardiology, seeing this kind of patient, discussing it together and then making decisions as to who benefits from what."

Tony acknowledged that many guys might feel uncomfortable discussing private issues with a doctor. But in his experience, talking about ED is nothing compared to lying naked on a table in Miami with everything except your penis covered by a sheet while people walk by as doctors induce an erection.

"If you can go through that, everything else is pretty easy," he said.