What the DUTCH Test Can (and Can't) Do for You

You may have heard of the DUTCH test, which purports to help you understand what's happening with your hormones during the menopausal transition. But what exactly can it tell you about hormones and do you really need to take it?

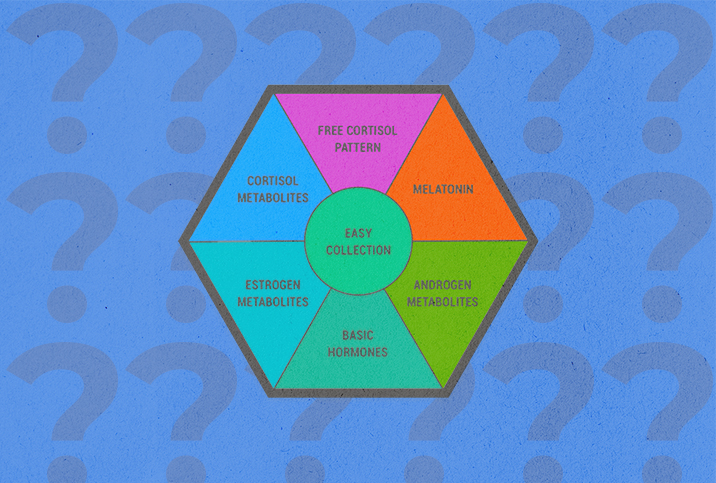

DUTCH stands for Dried Urine Test for Comprehensive Hormones. Precision Analytical Inc., the Oregon-based creator of the test, states on its website that the test results can help determine the cause of women's health issues so hormonal issues can be corrected.

The DUTCH test involves collecting four urine samples over a span of two days. The dried urine is sent to a lab and measured for hormone metabolites. The manufacturer states the test can use levels of estradiol, estrone and multiple estrogen metabolites to guide menopausal hormone therapy (MHT).

However, none of the medical societies' guidelines recommend it.

Can the DUTCH test really help with hormone treatment?

First, let's look at hormone replacement therapy (HRT) testing in general. There are traditionally three ways of evaluating sex hormones: salivary (spit) testing, blood testing and 24-hour urine testing, according to David M. Kimble, M.D., a urogynecologist at the Kimble Center for Intimate Cosmetic Surgery in Pasadena, California.

Kimble said the DUTCH test was born from a need to be as minimally invasive as possible, meaning you don't need to have your blood drawn or have your urine collected for 24 hours. Salivary testing is also relatively inaccurate, he added. The DUTCH test is easy to use, and urine is collected during the luteal phase of your cycle, giving you an average instead of a one-time snapshot, as with other tests.

Estradiol and progesterone are two hormones that start to decline as you near menopause. Levels fluctuate over the course of a cycle, especially in perimenopausal women. A single level-reading of these hormones provides little value, according to Nanette Santoro, M.D., a professor and the E. Stewart Taylor chair of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Colorado.

"Getting a snapshot of hormones at a single point in time, even if it's a lot of hormones, is not likely to lead to a eureka moment in diagnosis," Santoro said.

The DUTCH test doesn't just look at hormones, it also looks at how they're metabolized. The implication is that if you produce a lot of these metabolites, you're more at risk for estrogen-dependent cancers, such as breast cancer and uterine cancer. It's true that too much estrogen can result in the overgrowth of these two tissues, which can result in cancer.

'Getting a snapshot of hormones at a single point in time, even if it's a lot of hormones, is not likely to lead to a eureka moment in diagnosis.'

However, estrogen metabolization is more complex than that. One way that estrogen may cause cancer is with the metabolite 4-hydroxyestradiol (4-OH), which is what estrogen gets broken down into.

"Catechol estrogens, of which 4-OH is one, are thought to create more free radicals, which can damage DNA and thereby contribute to cancer risk," Santoro explained.

It's not really possible to know your risk for one of these cancers based on this metabolite alone, Santoro said. It's one of many risk factors for cancer. Estrogen metabolites can't really be measured in the bloodstream and then be used to determine what's happening with them in the uterus or breast tissues. It's just not the whole picture.

"From a research perspective, that's probably where DUTCH has had the better utility, [which] is they can measure these metabolites [in urine]. But right now, clinically, it's just not used," Kimble said. "If somebody has a little bit higher 4-OH, are you going to change your algorithm of surveillance for breast cancer or for uterine cancer? No, there's no current recommendation for that at all."

Do doctors recommend it?

The normal ranges in the DUTCH test are broad. During the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, estradiol can range from 200 to 700 picograms per milliliter (pg/mL), according to Kimble.

"If somebody comes back at 202, is she worse off than somebody who comes back at 681? Probably not," he said.

It's difficult for healthcare providers to use that data to give guidance in how they would prescribe HRT.

"What is the [provider] going to do with this information if they get the sampling report back?" Kimble asked.

One case in which a DUTCH test could be valuable is if you want compounded HRT, Kimble said. This is where a pharmacist customizes your hormone replacement therapy to your body. Your provider, if they're familiar with the DUTCH test, could take the information to come up with a treatment protocol for you. You can follow up in a few months to check your hormone levels. However, it's important to note that compounded hormones are not currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

All in all, there's probably some benefit to the DUTCH test. But it's much more costly than a blood test.

"You have to weigh that cost-benefit ratio," Kimble said.

Your best bet is to talk with your provider about the options and whether the DUTCH test could help with treatment.