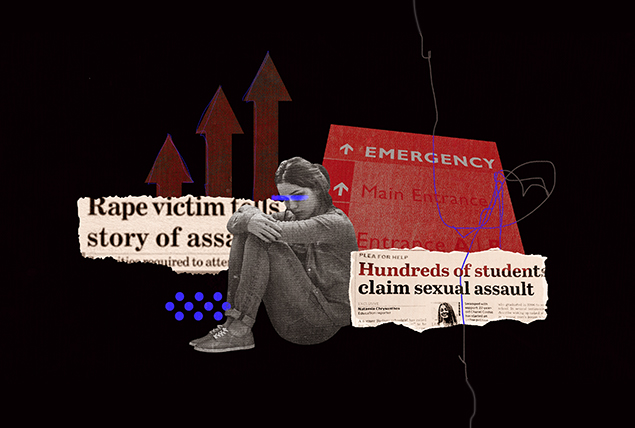

What Can We Do About Sexual Assault on College Campuses?

A lack of sexual consent at college is common. Roughly 13 percent of all undergraduate and graduate students experience sexual assault or rape, and women ages 18 to 24 have a three times greater risk of experiencing sexual violence than the female population at large, according to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN).

'This epidemic of [sexual assault] requires social surgery, not Band-Aids.'

University policies and protocols sometimes fail to meet the needs of students who report rape or sexual assault, according to the experts interviewed for this story.

What counts as sexual assault?

Are you wondering, "Was I sexually assaulted?"

Sexual assault can include any unwanted sexual activity, from touching to rape. Though sexual assault is prevalent on college campuses, many survivors are left without a blueprint for navigating the experience.

End Rape On Campus (EROC) is an organization that provides direct support for survivors on campuses.

The group recently launched the Campus Accountability Map and Tool. It's the first tool of its kind to track individual university policies on sexual assault, prevention efforts, available survivor support and data about reported sexual assaults among more than 750 colleges.

EROC's tool is useful for anyone who might be navigating their college campus protocol, but it also highlights the inconsistencies across university policies. It spurs questions about how institutions can better support male and female survivors. Yes, men are sexual assault victims, too.

How can universities prevent sexual assault?

"Campuses should have a fully formed year-long curriculum that touches on different aspects of combating sexual assault. Many colleges only have a sexual violence prevention program at orientation or an online module for their students to complete," said Stacey Rose, a Ph.D. student and sex educator at Pearbond in Somers Point, New Jersey.

It's a useful launching point but not enough.

There needs to be more education on the gray areas of consent, said Allyson West, J.D., and Kelly Olivier, J.D., trial attorneys in Chicago and founders of Themis, an all-women trial group that represents women in sexual assault cases.

"These initiatives should include mandatory courses in which the campus defines what is consent and what is not consent, and ensure these instructions include both verbal and nonverbal responses that provide students with real-life examples of what sexual assault can look like," the attorneys said.

'In a perfect scenario, a university would have specialized individuals on staff to consult with victims from a legal perspective, a medical health perspective and a mental health perspective.'

Courses need to include examples in the context of interactions with individuals with whom a person has a preexisting relationship, according to West and Olivier. About 85 percent to 90 percent of sexual assaults reported by college women are perpetrated by someone they know, according to the National Institute of Justice.

One instance where colleges must take a bolder stance is when a victim is unconscious, which is always assault, said Joy Farrow, a retired deputy sheriff in the Orlando, Florida, area and co-author of "Street Smart Safety for Women in Florida."

"Alcohol is the most prevalent and legally available date rape, or acquaintance rape, drug there is, and is continually used as a defense for assailants," Farrow said.

At least 50 percent of student sexual assaults involve alcohol, according to American Addiction Centers.

"Administrations need to take sexual assault seriously, stop believing it is inevitable when hormones and alcohol are combined in a toxic cocktail," Farrow said.

How do universities fail to meet the needs of students?

Sexual assault education is inadequate, according to Rose.

"Imagine you were taught to drive a car only by learning about car accidents. This is sexual assault education on college campuses," she said. "Too much of our education focuses on avoiding victimization instead of finding ways to reduce perpetration.

"Initiatives around bystander intervention, alcohol, refuting anti-consent messages in porn and media through practical applications of consent, and increasing understanding of the role of the freeze response are gaps that consistently come up."

Better wording when a person reports a sexual assault is crucial.

"Unfortunately, especially in the too-often gray and blurred-line areas of sexual assault, it comes down to a he-said/she-said analysis for the university. In these instances, the specific wording used when questioning a victim is extremely important but can be overlooked and is too frequently insensitive and outdated," West and Olivier said.

These outdated tactics can cause re-traumatization for victims.

Universities that fall short of supporting survivors do so by not taking bold enough stances and supporting their students.

"Universities are so afraid of litigation they become robotic and chaotic," Rose said. "Survivors feel harmed all over again because they are treated like a cog in the Title IX or sexual misconduct process and not like a person."

Title IX prohibits discrimination based on sex in education or any activity receiving federal funding. The law also allows colleges to handle cases of sexual assault, which advocates say is insufficient.

What should university policies and protocols include?

Only 20 percent of female student victims ages 18 to 24 report to law enforcement, according to RAINN. A majority of survivors never report their assault to anyone, Rose said. Farrow said it's significant for universities to make those who have experienced sexual assault feel safe to report it and instill that it is never the person's fault.

When a student does report an assault, there needs to be better support in place from the get-go, including campus police training on complete report writing, which Farrow said typically minimizes a victim's narrative and misses crucial details.

Students also need to know there will be clear consequences for them.

"Should an assailant be found guilty, perps should be expelled, lose scholarships, including athletics, and other stringent measures, not just temporarily suspended and then free to resume their daily lives after a slap on the wrist," Farrow said.

In a perfect scenario, a university would have specialized individuals on staff to consult with victims from a legal perspective, a medical health perspective and a mental health perspective, according to West and Olivier.

Where can sexual assault victims go for help?

Colleges and universities can keep safety and support in mind. Farrow said it's key for campuses to staff people with extensive sexual assault and trauma training.

"Victims may not remember or acknowledge their assault until days, weeks or months later," Farrow said. "Trained trauma residents can support the victims, no matter when they come forward."

If a university does not offer the support someone needs and deserves, there are resources outside of the institution for victims of sexual assault. Rose listed the Office of Civil Rights, hotlines like RAINN, or activist groups like Know Your IX or the National Sexual Violence Resource Center.

What is the statute of limitations on sexual assault?

The statute of limitations is the window of time an individual state has to charge a perpetrator. Some states have no statute of limitations for felony sex crimes, meaning someone can report an incident years after the sexual violence on campus occurred.

Under Title IX, someone has 180 days from the assault to report it.

The bottom line

"This epidemic of [sexual assault] requires social surgery, not Band-Aids," Farrow said, calling on universities to have bolder policies in place to support survivors.

Sexual assault is common, especially on college campuses. It is not your fault. Resources for support are available.