The True Cost of Overturning Roe v. Wade

Editor's note: This article is part of a series originally published in 2022, after the unprecedented leak of a draft decision by the Supreme Court of the United States that would overturn 1973's landmark Roe v. Wade ruling. At the time, the proposed removal of federal protection for abortion rights represented a seismic shift with far-reaching implications, many of which are now a reality for millions of American women. Giddy is committed to thorough and fact-based coverage of this issue and we present these original data-driven articles as a snapshot of America as it was preparing to navigate a changing landscape of abortion rights.

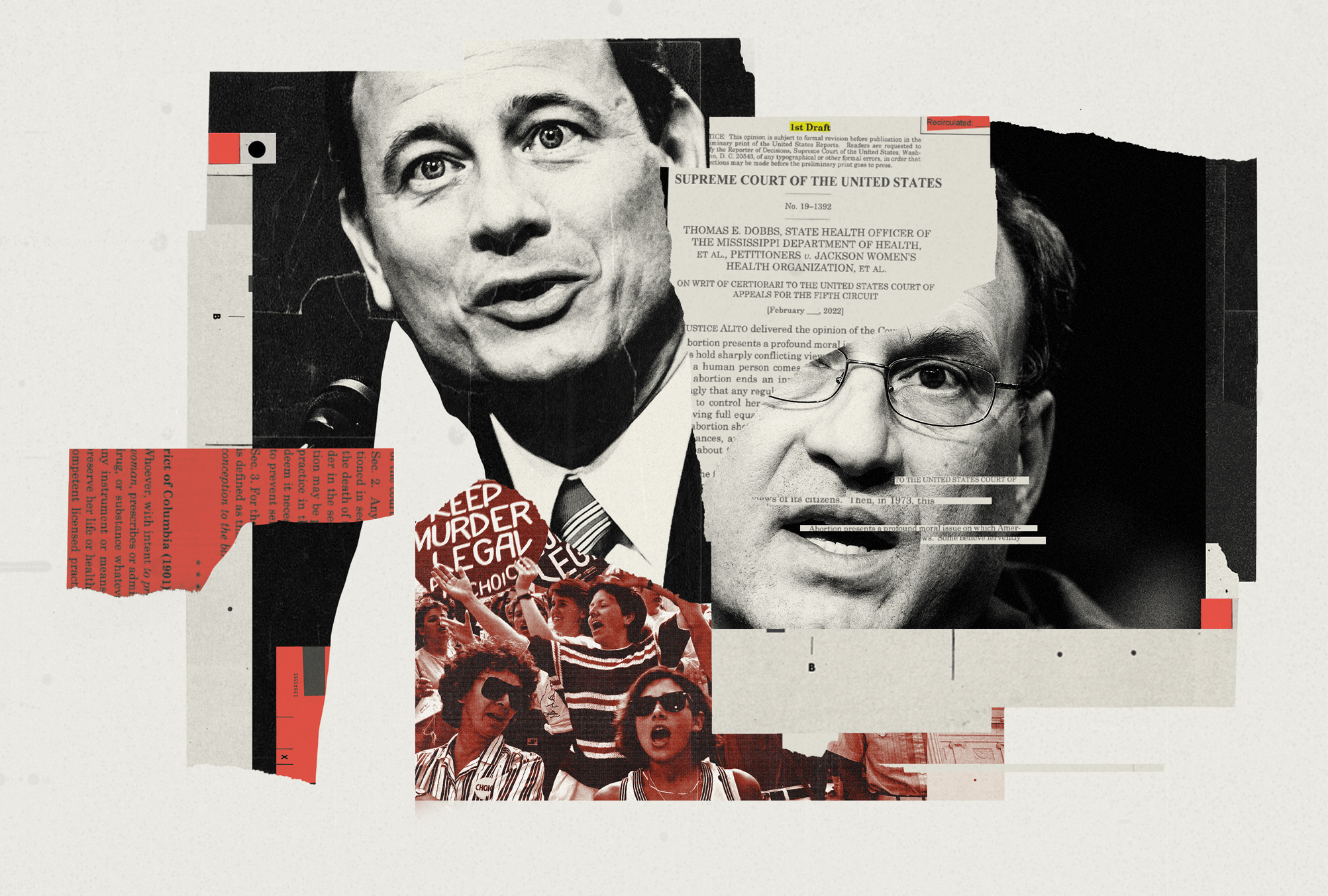

This summer, the U.S. Supreme Court is expected to announce its decision in the case of Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, in which the state of Mississippi is asking the high court for the constitutional right to ban some previability abortions if it does not "burden a substantial number of women."

When Justice Samuel Alito's draft opinion on the case leaked in early May, it gave Americans a glimpse of what's widely considered likely to come: the overturning of Roe v. Wade and the end of legal abortions in much of the United States after nearly 50 years.

Twenty-six states are expected to ban abortion if Roe is overturned this summer, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a research and policy group focused on sexual and reproductive rights. Thirteen of the 26 states have "trigger" bans in place, meaning abortion will automatically be outlawed once Roe is overturned. These states, mostly in the South and Midwest, have either retained their pre-Roe abortion laws or passed new restrictions more recently.

Abortion protections remain in place in densely populated states on the coasts, across the Mid-Atlantic and in a few blue Midwestern states. But even so, nearly 60 percent of American women of reproductive age—approximately 40 million women—live in a state that will ban abortion outright or severely restrict it.

U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has warned that removing abortion protections could be catastrophic to the American economy.

"I believe that eliminating the right of women to make decisions about when and whether to have children would have very damaging effects on the economy and would set women back decades," she said at a Senate Banking Committee hearing on May 10.

In this article, we discuss those far-reaching economic implications, including rising healthcare costs, declining workforce participation and the burden on taxpayers.

Abortion trends in America

Since 1969, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has tallied the number of legal abortions in its annual abortion surveillance report. But these numbers are incomplete.

While the CDC requests data from the health departments in all 50 states, as well as New York City and Washington, D.C., those areas aren't required to share this data. In addition, these totals include only legal abortions, not ones that have been self-induced or are otherwise considered illegal.

The potential healthcare cost of overturning Roe

Overturning Roe would have impacts on individual women and families, as well as on the American healthcare system more broadly.

Many pregnant people pay for an abortion out of pocket, and the cost has increased over time. The Hyde Amendment prevents federal funds, including Medicaid, from covering the expense of an abortion, except in the cases of rape, incest or endangerment to the mother's life. Some states limit private insurance carriers from covering abortion costs, as well.

Between 2017 and 2020, the cost of both medical and first-trimester surgical abortions increased. Likewise, the further along the pregnancy, the more expensive the procedure becomes:

- The average cost for a medication abortion was $560 in 2020, though the cost can go up to $750 today.

- First-trimester and second-trimester surgical abortions cost $575 and $895, respectively, in 2020.

Healthcare experts have long held that abortion is safe—safer than pregnancy, in fact. In 2018, the last year of reporting data, there were two abortion-related maternal deaths in the U.S., according to the CDC's 2019 report. That year, 660 women died due to causes related to their pregnancies.

"Abortion-care bans have far-reaching consequences for reproductive health care," said Sarah Horvath, M.D., M.S.H.P., an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Penn State Health Hershey Medical Center. "For patients who are able to travel to access this care, it will push people further into pregnancy and increase the cost of care. While abortion care is safe at any gestational age—14 times safer than childbirth—it has fewer complications the earlier you are able to access care."

Abortion providers in "safe haven" states may be unable to meet growing abortion demand from other states, in an area of medicine where there's already a dearth of providers.

"I trained for a decade to provide comprehensive, quality reproductive health care," Horvath said. "We are going to be 10 years behind the surge, even if we start training more physicians now."

Not only are there fewer OB-GYNs to provide reproductive health care—particularly in poor, rural counties—but there is also a nationwide shortage of pediatricians and primary care physicians to care for babies and children.

Depending on where they live, pregnant people may not even have a hospital nearby to deliver their baby. Nearly 54 percent of rural counties in the U.S. had no hospital-based obstetrics service in 2014, according to a 2020 study published in JAMA. That number dropped by 3 percent between 2014 and 2018. In 2020 and 2021, at least 21 rural hospitals closed.

These rural closures tend to occur in areas that are less populated, more remote and have higher proportions of Black to white residents, according to a 2021 report by the Pew Charitable Trusts. In Texas, which has some of the most restrictive abortion laws in the country, only 40 percent of rural hospitals offer labor and delivery services. As closures increase, so does the risk of infant and maternal mortality, the JAMA study reported.

Ultimately, low-income women of color would feel the impact of abortion restrictions the most. Many states, including Mississippi, that have the most restrictive abortion laws have worse health outcomes for women and children, including higher rates of maternal mortality. These states also spend the least amount of money on social programs that could improve these outcomes.

"The decision to overturn Roe will cause a public health emergency that will reinforce the chasm of disparity between Black women and white women, and between those who can afford to buy their freedom and those whom the state has doomed to perish in entirely preventable ways," said Amelia Maris Bonow, founding director of the reproductive rights advocacy organization Shout Your Abortion in Seattle.

The potential economic impact of overturning Roe

Since the 1970s, the number of women in the workforce and obtaining college degrees has grown. In 1970, only 11 percent of women in the U.S. had a bachelor's degree or higher, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. In 2016, the figure was 42 percent.

Today, women are more likely than men to finish college and earn a degree. Experts worry education and workforce participation numbers for women—which already declined during the COVID-19 pandemic—could plummet if Roe is overturned.

"There is an extensive amount of research in economics showing that childbearing has large costs for women in terms of reduced earnings and labor force participation," said Sarah Miller, Ph.D., an assistant professor of business economics and public policy at the University of Michigan. "We don't see similar patterns for men. Since women are about half of the labor force, any law changes that result in large changes in childbearing can be expected to reduce total labor force participation and possibly make it even harder for employers to hire and retain the workers they need."

Some large companies are trying to get ahead of this possibility by pledging to help employees access abortion care. Salesforce has offered to help relocate employees and their families who want to move out of states expected to ban abortions. Amazon, Tesla and Starbucks have said they would cover travel costs for workers seeking abortions—a cost that is prohibitive to many people.

"This will help some women, although it could widen inequality in access to reproductive health services since many of the women who will get these additional employer benefits will be higher earners," Miller said.

In 2018, the last year of reporting data, there were two abortion-related maternal deaths in the United States—that same year, 660 women died due to causes related to their pregnancies.

Katie Oliviero, Ph.D., an associate professor of women's, gender and sexuality studies at Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, echoed Miller's concerns.

"Because our stratified labor systems help ensure people of color are overrepresented in lower-paid service, domestic and agricultural work, where there is little or no paid health or parental leave, women of color are disproportionately impacted by these barriers," she said. "Unpaid FMLA [Family and Medical Leave Act] doesn't apply in many of these sectors, so these individuals can be fired for taking time off to access abortion care."

The groundbreaking Turnaway Study explored the economic implications for women who were denied abortions compared to those who obtained them. Researchers studied 1,000 women in 21 states who tried to get abortions at about the time of their state's legal gestational limit. Some were able to get an abortion just in time (the "Near Limit" group), while others were too late and were denied abortions (the "Turnaway" group). Here's what the study found:

- The Turnaways were less likely to have enough money to cover basic living expenses, such as housing and food.

- The Turnaways also had lower credit scores, higher amounts of debt and more negative public financial records, such as bankruptcies and evictions.

- The children of the Turnaways group were more likely to live below the federal poverty level than kids born from subsequent pregnancies to the Near Limit women who had received abortions.

Laura Wherry, Ph.D., an assistant professor of economics and public service at NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service in New York City, recently co-wrote a paper with Turnaway Study leader Diana Greene Foster, Ph.D. They looked at 10 years' worth of credit report data—before and after the "abortion encounter" where subjects had or were denied abortions—from the Turnaway Study's participants. Wherry and Foster found economic repercussions to the Turnaway women for years after being denied abortions.

"This work clearly shows that denying women access to abortion services can have large and long-lasting negative effects on their economic well-being," Wherry said.

The potential legal impact of overturning Roe

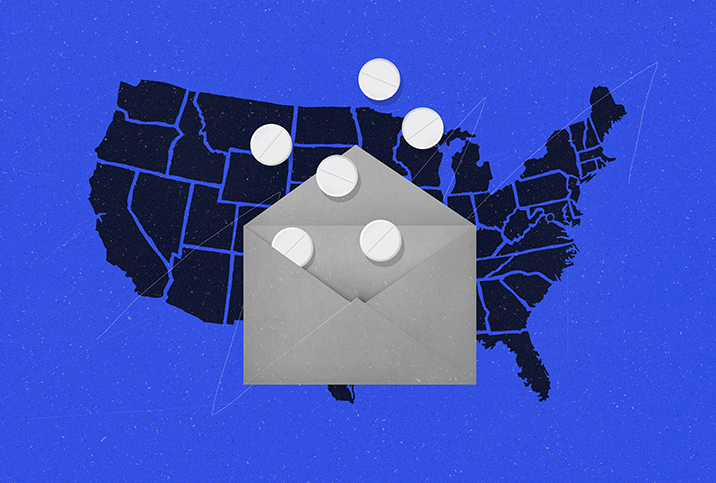

If Roe is overturned, will pregnant women be arrested for seeking abortions? Will healthcare providers be prosecuted for administering them? Will abortion pills be obtainable where abortion is outlawed? Many questions arise, but here's what has already happened.

More new statewide abortion restrictions became law in 2021 than ever before. There were 106 in total, reported The 19th, an independent news source. Arkansas alone passed 20 new restrictions last year. This trend has already cost states millions of dollars. During 2016-2019—before many of the newest restrictions were implemented—taxpayers were on the hook for almost $10 million in attorney fees for abortion providers, The Washington Post reported. Taxpayers are also footing the bill for attorneys for the states. As more restrictions are implemented, and if states begin prosecuting abortion seekers and providers, the costs will grow.

Some "safe haven" states are using state money to shore up abortion protections. Oregon has set aside $15 million for a "reproductive health equity fund." In New York, 7,000 abortions each year are given to people from out of state, but that number is expected to climb to 32,000 annually if Roe is overturned. The state has introduced a bill to spend $50 million to bolster abortion access. California Governor Gavin Newsom proposed spending between $57 million and $68 million to beef up access and cover abortion costs for people unable to pay for them.

In many states, grassroots funds to help low-income women pay for abortion-related costs would likely be tapped out—and contributing to such funds, or assisting pregnant people in other ways, could mean legal jeopardy in certain states.

"Private individuals who donate to an abortion-access fund could be sued," Oliviero said. "So could a parent, relative or friend who pays for termination or drive[s] an individual to a care provider. Dobbs [v. Jackson Women's Health], like [Texas'] SB8, will embolden states to explore more of these measures."

It's difficult to know for sure what impact abortion bans may have on the legal system. But a 2001 study by economists Steven D. Levitt and John J. Donohue III about abortion and crime rates is getting attention yet again. First published as a research paper (with a summary later included in Levitt's 2005 book, "Freakonomics"), the economists found causation between higher abortion rates and lower crime rates following the passage of Roe v. Wade in 1973.

Crime rates for both violent and property crimes had risen 80 percent since the mid-'70s peaked in late 1989 and began dropping rapidly in the 1990s. Levitt and Donohue's hypothesis for the reason for the decrease? Fewer unwanted pregnancies, due to legalized abortion.

In "Freakonomics," Levitt wrote about other research that found a typical child who went unborn would've been 50 percent more likely to live in poverty and 60 percent more likely to grow up with just one parent if they'd been born—what some experts see as two of the strongest predictors of future criminality.

The Levitt-Donohue study has not been without its critics and detractors. Some researchers have challenged the methodology. Some have researched other potential reasons for the crime-rate drop that started in the 1990s, either instead of or in concert with legalized abortion, such as the removal of lead from gasoline, which began in the 1970s. Levitt and Donohue updated their research in 2019 to look at more recent crime and abortion rates, from 1997 to 2014 and found the same patterns and results.

Big questions exist about how individual states would navigate their differing designations, and how abortion would be prosecuted or protected if a resident of one state travels to another for the procedure. The already chasmic political and social rifts among Americans could widen even more.

"While states have been legislating abortion differently for years, Roe maintained a minimum level of abortion legality, if not practical access, that applied across states," said Kathleen Marchetti, Ph.D., an associate professor of political science at Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. "Should Roe be overturned in part or in its entirety, anti-abortion states may go further by attempting to regulate state residents' access to abortion across state lines. This raises constitutional questions about states' ability to impose their own laws across state lines."

Beyond the purely economic impact, experts say the true cost of denying women abortions is far greater—and less easy to tally or quantify. Arin Reeves, Ph.D., a Chicago-based author and founder of the workplace-culture research and advisory firm Nextions, worries about the cumulative emotional toll on women, pregnant or not.

"Feeling devalued by our country and its laws has an incalculable impact on women's mental health and wellness, and will be experienced by women way beyond any reproductive choices they need to make," Reeves said.

Abortion is a medical procedure that is currently illegal or restricted in some portions of the United States. For more information about the legality of abortion in your area, please consult a local healthcare provider.