What You Should Know About Hashimoto's Thyroiditis

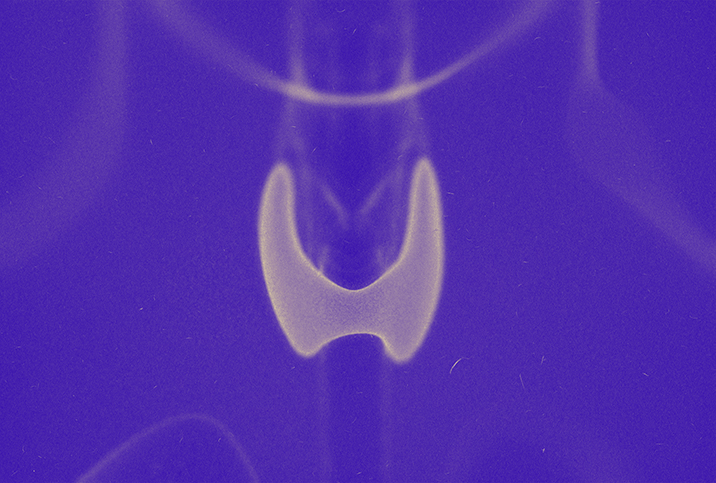

The thyroid gland's diminutive size belies the weighty roles it plays in growth, development and metabolism. Malfunctions can impact everything from energy levels to mental health and more.

Hashimoto's thyroiditis, or Hashimoto's disease, is an autoimmune disorder of the thyroid. According to the National Library of Medicine, it affects about 1 percent to 2 percent of the U.S. population, most of whom are middle-aged women.

Despite its prevalence, people with Hashimoto's often live with the condition for years before receiving a diagnosis, partly attributable to the disease's pernicious nature. However, flawed diagnostic protocol and a lack of understanding of the condition might also play a role.

What causes Hashimoto's?

As with other autoimmune conditions, in cases of Hashimoto's, the immune system misguidedly perceives the body's healthy organs and tissues as harmful invaders. In order to combat the threat, the immune system sends an infantry of white blood cells (lymphocytes), which produce antibodies that attack and destroy thyroid cells.

As a result, the thyroid becomes inflamed and its functionality diminishes. Eventually, it can no longer produce sufficient hormones (most notably T4 and T3), and that can lead to the presentation of Hashimoto's symptoms.

Often, Hashimoto's-related thyroid damage causes hypothyroidism—an underactive thyroid. However, Hashimoto's can also cause hyperthyroidism—an overactive thyroid—though this is less common.

Experts aren't sure what causes Hashimoto's, though genetic and environmental factors likely play a part. People with other autoimmune conditions are at higher risk, as are people with a family history of the disease. Women are far more likely to get Hashimoto's than men, and many develop symptoms around the age of menopause. For these reasons, researchers think sex hormones may be a contributing factor.

Some scientists believe parasitic, yeast or bacterial infections originating in the gastrointestinal tract might trigger certain autoimmune conditions, including Hashimoto's, but more research is needed. Excessive iodine intake or radiation exposure may also increase a person's risk.

Spotting the symptoms

Symptoms vary from one individual to another, but some of the most common include a swollen thyroid gland, fatigue and weakness, increased sensitivity to cold, hair loss, unexplained weight gain, a puffy face, dry skin, menstrual changes and joint pain or stiffness.

An underactive thyroid is strongly linked to depression, to the extent that the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists advises everyone diagnosed with depression to be evaluated for hypothyroidism.

One study published in Panminerva Medica found that even a slight decrease in thyroid hormone could adversely affect mental health. In the study, 63.5 percent of participants with subclinical thyroid problems—or those with symptoms of hypothyroidism who did not meet the diagnostic criteria—exhibited symptoms of depression.

Jennifer Erickson, a health psychologist, was diagnosed with Hashimoto's at age 16. She recalls feeling "horribly tired" despite having no problems sleeping.

'I could sleep 12 hours and want to sleep more—absolutely no energy.'

"Everyone thought I might have mono because of my age," she explained. "I would sleep but just couldn't stay energized. I was always lethargic, but to a really bad degree."

Erickson has since had a "lifetime of experience" living with the disease, and has spent several years helping patients with similar challenges. She noted that she has mostly managed the condition with medication and strategic lifestyle choices, and it hasn't prevented her from leading an active, fulfilling life.

Despite her management, she has a slower-than-average metabolism, feels almost constantly cold and has lived with "being a little tired" since her teens. She also experiences periodic flare-ups, where imbalanced thyroid hormones cause symptoms to intensify. These have become more frequent with menopause.

"If my thyroid levels do go out of range, then I feel lethargic like you can't imagine," she said. "I could sleep 12 hours and want to sleep more—absolutely no energy."

Diagnosis is not always easy

The diagnostic process usually includes a physical exam: Checking for an inflamed thyroid gland manually or through ultrasound, a medical history evaluation or one or more blood tests—including a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) test and, sometimes, a free T4 (thyroxine) test.

The pituitary gland produces the TSH hormone to prompt the thyroid to produce hormones. If the thyroid is underactive, the body will produce more TSH to get it back up and running.

"Traditionally, a TSH of less than 10 but greater than 5 would diagnose hypothyroidism," said Tara Scott, M.D., an integrative GYN and hormone specialist. "For a TSH between 5 and 10—the normal cutoff is more than 4.0—it is called 'subclinical hypothyroid,' and no treatment is suggested."

Free or unbound T4 circulates in the bloodstream, unattached to a protein. Low levels indicate the thyroid isn't producing enough hormones. A doctor might also order an antithyroid antibody test to check for antibodies that could increase a person's likelihood of developing Hashimoto's.

Because TSH levels often increase dramatically before a significant change in T4 levels, many doctors only order a TSH test. However, for a small percentage of people with Hashimoto's, a TSH test is insufficient.

Scott, who also has Hashimoto's, noted that a TSH test could produce typical results even if thyroid hormones are low.

"It typically takes many years of symptoms before patients are diagnosed," she added. "High cortisol—think stress hormone—can suppress TSH release from the pituitary, so it will be 'falsely normal' when there is disease present," Scott said. "In addition, the TPO antibodies are rarely ordered or followed by traditional doctors. We order TSH, free T4, free T3, reverse T3 and TPO and thyroglobulin antibodies."

Even if a patient exhibits several symptoms, Scott noted that getting doctors to act when lab tests are only "mildly abnormal" can be challenging.

"You really do need an endocrinologist to extrapolate your bloodwork," recommended Erickson.

Treating the uncurable

There is no cure for Hashimoto's, but it's highly treatable with a combination of medication and lifestyle changes.

Scott noted that medication usually includes daily doses of Synthroid or Levothyroxine, synthetic replacements for the T4 hormone. However, this alone may not suffice.

"Although it is bioidentical, some people cannot convert T4 to T3 efficiently, and T3 is really the active form," Scott explained. "Things that can slow that conversion from T4 to T3 are low iron levels, low vitamin D, low selenium and stress. And let's be honest—who hasn't had stress the last two years?"

Scott and Erickson recommend lifestyle changes to supplement medication, including getting regular exercise and eating an anti-inflammatory diet.

The "autoimmune protocol diet" often recommended for people with autoimmune conditions eliminates or significantly reduces several foods thought to cause or exacerbate inflammation. This includes gluten, dairy and soy.

"I can eat gluten and dairy, but my body actually feels better and less inflamed when I don't," Erickson said. "So I'm like 95 percent dairy- and gluten-free, which also helps the weight. I try to keep active [and] work out to keep my metabolism working well. But I do feel like I have to work out more than the average person. I still have energy and do many things, but there are times I am just tired. Again, I have lived with this since [I was] 16, so I haven't let it stop my life from being fulfilling and active."