Jumping Through Hoops: Barriers to Gender-Affirming Care

The transgender population of the United States—historically, a difficult number to pin down—has garnered increasing attention in recent years, both in headlines and in research. According to a study published in June 2022 by UCLA's Williams Institute, one of the most comprehensive attempts to measure this population to date, roughly 1.4 million Americans identify as transgender. That's more than double the previous estimate by the Williams Institute in April 2011.

Despite this increased visibility, confusion and misinformation about the nature of this community remain, including the significant barriers to the health and well-being of its varied population.

There is no "right" way to be transgender. Despite the prevalence of deeply ahistorical assumptions that trans and gender-nonconforming communities have emerged seemingly from nowhere over the past century, there's an enormous breadth of people, bodies and experiences that fall loosely under the umbrella term "trans."

trans·gen·der (adjective): A broad term that describes individuals whose gender identity is different from the gender they were assigned at birth.

Highlighting this diversity is important, not least because every trans person has different needs. Not all trans people seek hormone therapy or gender confirmation surgeries to alleviate their dysphoria.

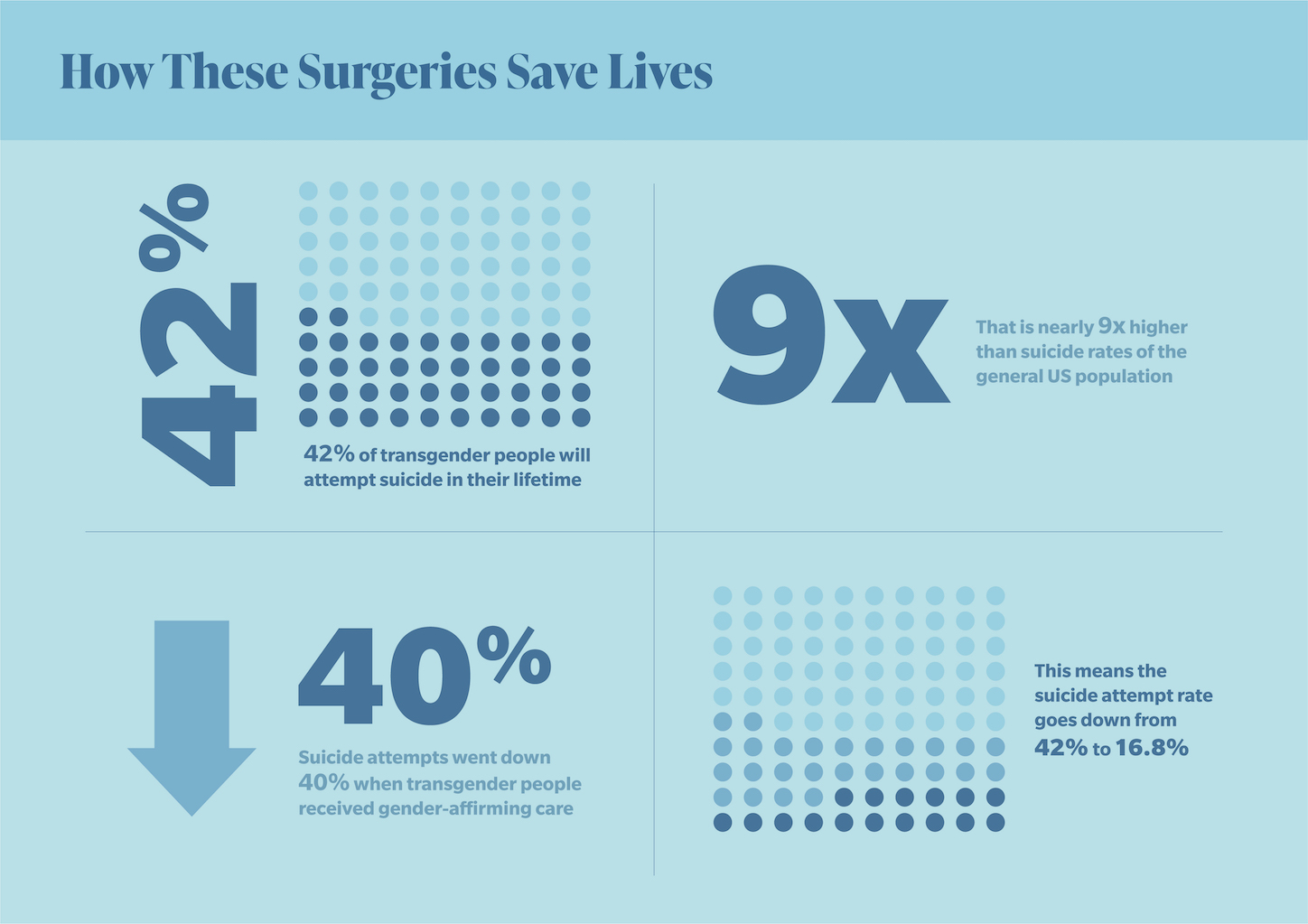

But for those who do, these procedures are critically important. Both the American Medical Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics have affirmed the importance of access, particularly among trans youth, a demographic with an unusually high prevalence of suicidal ideation. Research indicates that gender-affirming care reduces suicide attempts among transgender individuals by as much as 40 percent. Unfortunately, those who do require these services face an uphill battle against a healthcare system that has proved inadequately equipped for that purpose.

Part of the problem is the way we discuss trans healthcare. Too often, such care is treated as a niche issue unworthy of serious dissection, let alone reform. Statistically, trans people make up less than 1 percent of the U.S. population, which makes it easy for politicians to sweep their needs under the rug.

But in attempting to accurately depict the barriers to care, trans healthcare must be discussed within the wider context of systemic failures that impact huge swaths of the U.S. This includes the lack of universal healthcare and the inaccessibility of affordable insurance policies. There's also the political hand-wringing, which results in the chronic underfunding of so-called controversial sectors, such as sexual, reproductive and mental healthcare. The fact that trans healthcare directly impacts so little of the population doesn't negate its importance. Rather, it positions such care as an ideal case study to reveal broader institutional failings.

A second issue is the comparative lack of long-term research on trans healthcare. In 2019, the journal Deutsches Ärzteblatt International published research that indicates the quality of life improves after sex reassignment surgery. However, researchers noted this work was an aggregation of 13 papers that collectively had a "moderate to high risk of bias."

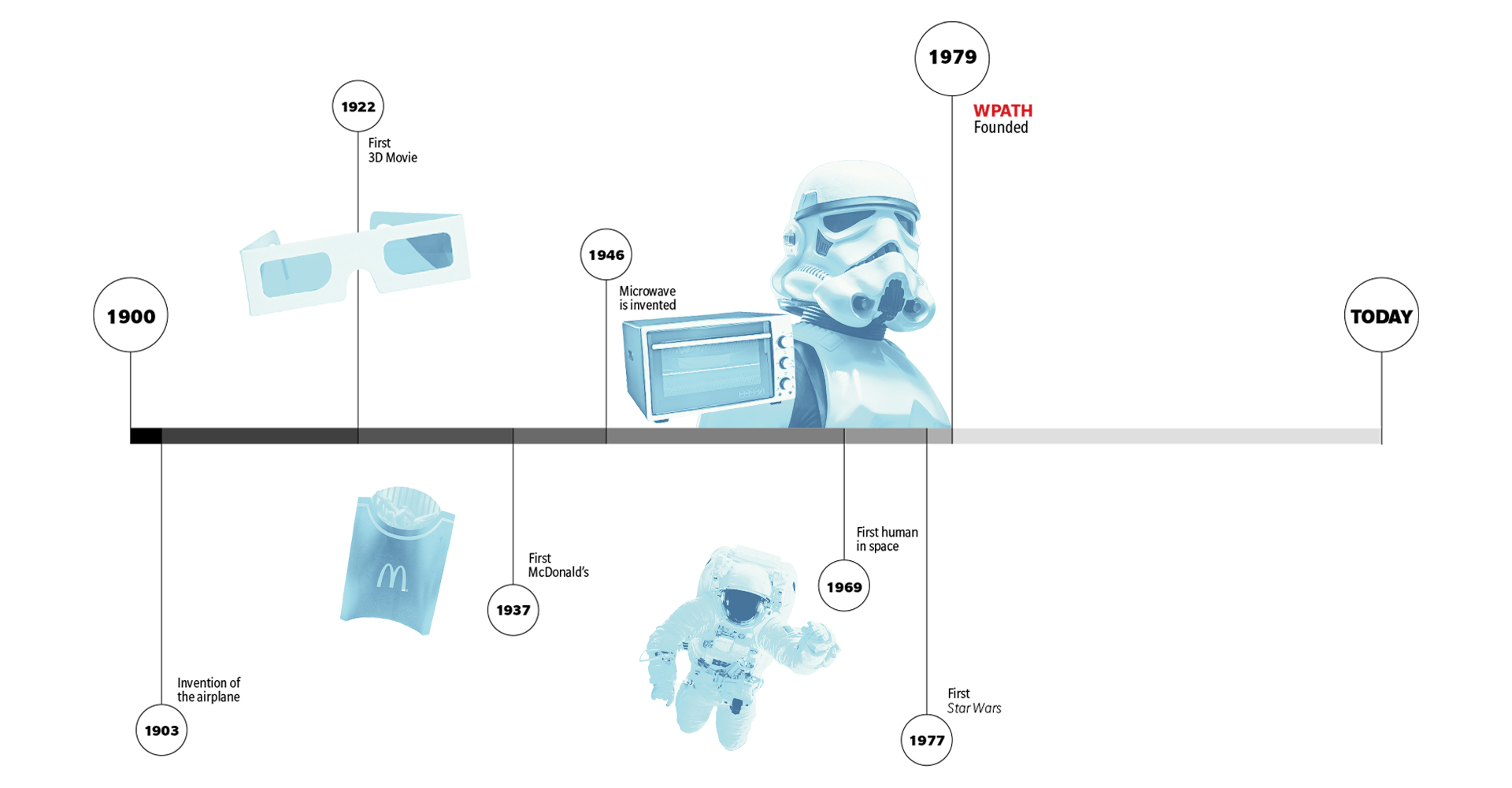

Here, it's important to note the historical context. It was in 1979 that the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) released its inaugural Standards of Care document, which has since been revised seven times. This document is often cited as the advent of modern trans healthcare, effectively making the entire system just two years older than the earliest millennials.

Despite the relative newness of trans healthcare, endless anecdotal evidence shows that surgeries, hormones, puberty blockers and other healthcare for trans youth can be lifesaving interventions. Still, there's a steady flow of mainstream transphobia often drowning out these lived experiences. What we're left with is a system fraught with miseducation, stigma and a seemingly endless list of barriers to vital gender confirmation surgeries.

Historical discrimination

Step one in accessing trans healthcare requires trusting the system enough to even seek it in the first place. Patients must jump through numerous hoops before gender confirmation surgeries are even on the table. These all require extensive engagement with medical professionals, which can be intimidating and fear-inducing for marginalized groups that have been historically underserved—or outright abused—by the U.S. healthcare system.

Dominique Morgan, a musical artist and sexual educator in Omaha, Nebraska, believes there is still a lack of awareness that many trans people—especially Black trans people—have had only negative experiences of engagement with the medical system.

Ample research exists to corroborate this claim. A recent Kaiser Family Foundation report found that only 59 percent of Black respondents trusted doctors "almost all of the time or most of the time," compared to 78 percent of white respondents. There's also less formal research on trans patients—some of the most recent in-depth reports were authored following the rollback of some key healthcare protections—but it's common knowledge within the community that "whisper networks" are relied upon to source trans-friendly providers.

In April 2016, research published in the Current Opinions in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity journal summarized barriers to trans healthcare, including a lack of insurance coverage as well as "unfriendly office environments and perceived stigma for both the patients themselves and the providers of transgender healthcare."

Insurance access is often political, too. Historical policies, such as redlining, have created long, intergenerational impoverishment of Black communities in particular. In general, current workplace discrimination often makes it harder for trans people across the board to find work, especially work that comes with comprehensive healthcare.

Trans communities are often overrepresented in sex work, for example. Criminalization drives those trades underground and adds to the stigma that can be used to deny healthcare coverage.

Access to health insurance has improved over the past decade, according to Loren Schechter, M.D., a Chicago-based surgeon specializing in gender confirmation care.

"Medicare removed its blanket exclusion for covering gender-confirming procedures, and many private insurers then followed suit," he said. "I would say the general trend in terms of insurance and payers has been positive."

However, this trend is somewhat based on location. For trans people in rural areas, in particular, geography is a huge barrier to accessing unbiased, affirming care. Few practitioners in the country are trained to deliver the best possible care, especially lower surgeries. Those who have this training are scattered across the country and in extremely high demand due to extensive waiting lists.

This situation can also create an additional financial barrier. Trans people—already more likely to live in poverty than their cisgender counterparts—have to pay out again to travel to these providers.

The necessary expansion of telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic does offer a glimmer of hope in terms of expanding this access to affirming healthcare.

"There's so much trans care in general which isn't accessible to people who aren't in large urban areas," said Caleb LoSchiavo, MPH, a doctoral candidate at Rutgers University in New Jersey. "Telemedicine allows people to access that so much more easily, but there are still logistics to work out. It often has to be within the same state, because providers are licensed by the specific state. It can make it tricky to work out the details, particularly if you're prescribing medications."

The aforementioned 2016 report indicated that comprehensive training could alleviate the fears of stigma for trans healthcare. However, the roots of systemic racism and transphobia run so deep that a few training courses alone aren't likely to solve the problem.

"There is a pattern of care and love not happening for oppressed people, especially Black people," Morgan said. "The care exists—there's just a long tradition of it not being extended to Black and Brown folks."

Fortunately, especially in the case of clinics specializing in trans healthcare, active efforts to create an immediately inclusive environment are on the rise.

"There's obviously still work to be done, but we know that trans individuals have faced discrimination, which makes them reluctant to seek care," Schechter said. "In our hospital, we use name bands—there's often discordance between an individual's name and the name on their legal ID—and ensure all-gender bathrooms. Plus, institutions have been working with electronic medical records to move beyond a binary definition of male or female."

These are all improvements, albeit heavily dependent on location. Numerous red states are notoriously hostile to trans communities (exemplified by a steady swell of anti-trans bills), as opposed to large metropolitan cities, where care is more readily available.

As a performer constantly on the road, Morgan has long relied on telemedicine to ensure access to healthcare. In December 2019, she came to the realization that her gender presentation or identity did not align with who she was, so she took a brief break and began seeking transition-related healthcare early the next year.

"Although the trans clinic was backed up, the person there recognized my name and pushed me up the list," she recalled. "Because of the insurance I have and because of my name in this community, I had started estrogen and testosterone blockers by the end of March [2020]. Doctors at the clinic wrote all of my letters, and I was able to get all of my IDs and everything changed."

Access to gender confirmation surgeries is almost always dependent on a diagnosis of gender dysphoria, sometimes known as gender incongruence. In a nutshell, this term describes the mental toil of feeling like your exterior doesn't align with your internal gender identity. For many trans people, surgeries are a key step toward alleviating this psychological pain.

Not everyone is as lucky as Morgan, who acknowledges the privilege her standing as a dedicated campaigner within the trans community afforded her. Gender dysphoria diagnosis is often a long, drawn-out process that requires extensive interaction with mental healthcare professionals and lengthy, often outdated questionnaires.

"I don't require an individual to have a diagnosis prior to surgical consultation but to move forward with surgery, we do need that assessment completed," Schechter said, adding that "most individuals will not so much as schedule surgery without a diagnosis of dysphoria."

A list of criteria needs to be met first: The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) defines gender dysphoria as "a marked incongruence between one's experienced or expressed gender and their assigned gender, lasting at least six months." But these assessments are rarely, if ever, carried out by trans people, meaning cis gatekeepers literally hold the keys to trans healthcare—and can lock the door shut at any time.

"It is frightening that oppressed people need permission from our oppressors to access what we need," Morgan said. "You just have to hope that these cisgender folks are empathetic."

It's not uncommon for clinicians to refuse a diagnosis several times, she said.

"Again, access is dependent on privilege," Morgan said. "It's a real struggle to be told no but to still carry on. It feels almost like a test."

Although the DSM-5 is written in language that includes nonbinary people, trans communities have a running joke that being diagnosed with dysphoria requires simplistic, binary answers.

"There definitely have been strides made in terms of nonbinary inclusion," LoSchiavo said. "It used to be all about gatekeeping. It was so rigorous that trans people would give a certain set of answers regardless of how they actually felt about their gender. Trans men would have to go in and be like, 'I was born a girl but I always hated dresses. I liked playing with cars, trucks and dirt, you know? I'm just such a man's man!'"

The distrust these policies create extends to mental health, too. Dysphoria is still classified as a mental disorder, which naturally means its diagnosis requires an extensive conversation with mental healthcare professionals.

"Within our system, you need two letters from a mental healthcare provider in order to get your surgery," LoSchiavo said. "What often happens is that trans people lie about their mental health in these settings, because they know they just need the letter."

Trans people are seemingly reluctant to speak in depth about any stigmatized mental health condition, especially schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder (BPD), among others. Saying the wrong thing could result in a professional blocking a diagnosis of dysphoria under the pretense of care and compassion, despite consistent evidence that gender confirmation surgeries have hugely important mental health benefits for trans people.

The waiting game

Even after someone successfully navigates the endless roadblocks of trans healthcare, surgeries can come with various stages and extensive waiting times—exacerbated even further by the COVID-19 pandemic.

In March 2020, Chicago's Weiss Memorial Hospital shut down entirely, with the exception of emergency surgeries. As a result, Schechter was unable to practice.

"That carried on for almost three months," he said. "And then, I think it was in June that we began doing outpatient surgeries again. In July, we resumed inpatient."

Despite the unprecedented challenges posed by COVID-19, statistics released by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons showed that more surgeries were still carried out in 2020 than in 2019—for trans women, at least. For trans men, top surgeries were up 15 percent, but genital surgeries were down 7 percent.

Trans-masculine lower surgeries are particularly difficult to access. These can be divided into two main categories: phalloplasty, which involves constructing a penis from skin grafts and implants, and metoidioplasty, which creates a penis using the tissue from the clitoris of trans men, enlarged through testosterone therapy. This is known as "bottom growth." Both procedures are complex, costly and require various stages. For phalloplasty, in particular, researchers are still undecided on the best, most fail-safe routes to long-term satisfaction.

This problem isn't unique to the United States. Earlier this year, the one United Kingdom clinic that offered trans-masculine lower surgeries lost the right to do so, leaving hundreds of trans men whose surgeries were between stages with dangerous, long-term complications. People who were still on the waiting list were kicked off.

Although GoFundMe remains a financial lifeline for members of the trans communities seeking surgery in the U.S., a recent journal article published in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery analyzed the impact of the Affordable Care Act on gender confirmation surgeries across America. Researchers used a database of 1,188 privately insured trans people, registered between 2007 and 2017, to gauge long-term trends and evaluate how many trans people could readily access care. Of these patients, only 161 accessed trans-masculine lower surgeries across the entire study period—81 accessed phalloplasty and 80 metoidioplasties.

This lack of access is also due to the high level of skill needed to carry out the surgeries. Fewer than 200 surgeons across the U.S. are trained for metoidioplasty and phalloplasty, according to TransHealthCare's nationwide practitioner database, and their skills are in high demand.

According to Schechter, the length of time between consultation and surgery can range from a few months to a few years, depending on the surgeon. More recent statistics are difficult to find, but a 2016 report by the Medicaid Coverage Database found average wait times of 14 to 24 months for confirmation surgeries, a number sure to have risen due to increased diagnoses of gender dysphoria and COVID-19's huge impact on U.S. healthcare.

Even after clearing these hurdles, a patient's weight can block them from accessing surgeries. Many surgeons use the body mass index (BMI) to flat-out deny care to heavier patients, but this metric was never originally intended to be used on an individual level and was developed with a largely homogeneous study population and subsequently abused by eugenicists.

For Schechter, the use of BMI requires a case-by-case approach.

"In my practice, there's no BMI limit on a mastectomy, for example," he said. "However, the likelihood of needing secondary surgeries or revisions is higher for heavier patients. For lower surgeries, BMI comes into play a bit more. We use a soft limit of around 35, but that doesn't mean people with a BMI of 36 would be excluded. It's an individualized assessment based on how someone's weight is distributed."

In his eyes, the BMI limit is designated with a patient's best interests in mind.

"With metoidioplasty, obese individuals might find the penis that's constructed may be obscured by fatty tissue in the pubic region, which might prevent them from using a public urinal," he explained.

However, it's undeniably heartbreaking to wait years for surgery only to find out during a pre-surgery consultation that your BMI is too high. This can be a devastating final hurdle for heavier trans patients already doubly vulnerable to medical bias, given the prevalence of medical fatphobia.

LoSchiavo echoed Schechter's emphasis on individual assessment but ultimately argued that practitioners should work on becoming size-inclusive. Trans people in desperate need of surgeries could be tempted to seek a less reputable surgeon who doesn't see BMI as a deal-breaker.

"BMI is garbage and it's not an indicator of health whatsoever. It certainly shouldn't be used to gatekeep surgeries," LoSchiavo said. "What ends up happening is that plastic surgeons who haven't done many confirmation surgeries see a gap in the market to fill, so they'll operate on people with larger BMIs but not actually know what they're doing. There are definitely predatory surgeons out there who could take advantage of this."

Endless obstacles

Gender confirmation surgeries are regularly described as "elective," the implication being that they're a choice. But research routinely proves that these procedures can be lifesaving, yet endless obstacles remain.

No system can change overnight. Trans communities across the U.S. are grappling constantly with deep-rooted histories of racism, ableism, transphobia and more within the healthcare system. From outright discrimination to harmful stereotypes, there's a complex web of bias to unravel before even mustering the courage to make the first appointment.

Inclusive environments mark a definitive step forward, but the process of being diagnosed with dysphoria drags out waiting lists and backs trans patients into rhetorical corners. The overwhelming sense is that there's a prescribed script of "trans-ness" that needs to be recited ad infinitum, distilled into easy soundbites so cis gatekeepers can check a box declaring patients are "trans enough" to be diagnosed with dysphoria and, therefore, allowed entry into yet more waiting rooms.

People with economic and other privileges can often leapfrog some of these hurdles, but with a pandemic-ravaged economy, more U.S. citizens than ever lack the coverage to access the care they need.

The needs of trans people who happen to be incarcerated, use drugs or sell sex often go undocumented and unmet due to stigma. Even when confirmation surgeries are penciled in, outdated yardsticks, such as the BMI, can throw a wrench into the works at the last minute.

Perhaps the biggest misunderstanding facing the trans community is the assumption that without access to trans healthcare, trans people simply don't medically transition. This is unequivocally false. Instead, desperate patients seek black-market hormones, cheap overseas surgeries and dangerous makeshift fillers sold through underground whisper networks. If the inability to access these lifesaving medical interventions doesn't kill trans people, the shady and often criminal methods they seek in desperation might well do the trick.

Within this context, the erosion of barriers to gender confirmation surgeries isn't just necessary, it's lifesaving.

Additional Resources

Find a transgender-inclusive medical professional

- To find a doctor who can perform gender-confirming surgeries, search TransHealthCare's database here.

- To find an LGBTQIA+ competent medical professional in a variety of specialties, search OutCare's database here.

- Online options for gender-affirming care include Folx Health and Plume. These subscription-based services connect individuals with LGBTQIA+ affirming medical professionals who specialize in prescribing estrogen and testosterone.

- Another option for low-cost, transgender-inclusive medical care is your local Planned Parenthood location. Many centers offer education, sexual health services, HRT, support groups and referrals to other local LGBTQIA+ friendly doctors.

Financial resources

This helpful guide from MoneyGeek gives an extensive overview of the costs of different medical procedures for gender-affirming care. This resource also dispenses advice and tips from four financial experts for financing gender-confirming surgery.

This resource from Strong Families provides a step-by-step guide for LGBTQIA+ individuals to select the healthcare insurance plan that is best for them.

Additionally, several organizations offer grants or scholarships to help transgender individuals pay for medical transition:

- The Jim Collins Foundation

- Genderbands Transition Grants

- Rizi Timane Trans Surgery Grant

- TransMission

- Stealth Bros & Co. Support Fund

- Black Transmen Inc. Surgery Scholarship

- Point of Pride Annual Transgender Surgery Fund

Mental health resources

- The Trevor Project is the world's largest suicide prevention and crisis intervention organization for LGBTQIA+ young people. You can reach their hotlines by chatting on its website, texting START to 678-678 or calling 1-866-488-7386. The Trevor Project website also has many resources and blog posts about various LGBTQIA+ topics.

- Trans Lifeline is both a hotline—call 877-565-8860 to speak with a transgender or nonbinary peer operator 24/7—and an online resource that includes helpful information on ID changes, self-care tools and community support.

- Pride Counseling is a subscription-based service that matches therapists who specialize in the LGBTQIA+ community with individuals who wish to see a professional therapist. This online model allows individuals to seek mental health care from the privacy of their home on their own schedule.

- It Gets Better Project has a library of thousands of videos of LGBTQIA+ individuals sharing their stories and offering hope.

- The Tribe offers free peer-to-peer support groups with specific focuses to best suit individual needs. The groups offered include AddictionTribe, AnxietyTribe, DepressionTribe, HIV/AidsTribe, LGBTribe, MarriageFamilyTribe, OCDTribe and TeenTribe.

- Transbucket is an online resource and peer-to-peer support group for transgender individuals, especially surrounding medical transition.

- TransMentors is an online community of transgender people that facilitates the pairing of mentors and mentees to provide assistance and support to newly transitioning individuals.

- TherapyDen offers a database of mental health providers who specialize in transgender care.

Other resources for transgender individuals

- Refuge Restrooms is a website and app (available on both iOS and Android) that seeks to provide restroom access for transgender, intersex and gender non-conforming individuals.

- Findhelp.org is an organization that connects individuals with financial assistance, food pantries, medical care and other free or reduced-cost help.

- Your Lessons Now offers in-person (in Portland, Oregon) or online (via Zoom) voice lessons for transgender individuals with trained vocal coaches.

- Point of Pride has a program that offers free chest binders to any trans person who needs one and cannot afford or safely obtain one.

- Facebook group Trans Job Connect U.S. offers employment services to all transgender individuals, including resumé writing and connections between individuals and affirming employers throughout the country.

- TransFriendly is a database of transgender-friendly businesses, including everything from barbers and gyms to wedding planners and places of worship.

- SAGE is an organization dedicated to advocating for and providing services to older LGBTQIA+ individuals.

- Transgender Map is a great resource for many aspects of transition, including medical and legal information, and tools for social transition, including handwriting changes, dating and clothing options.

How to be an ally to the transgender community

An ally is someone outside a marginalized community who advocates for that community. There are many types of allies who align with various causes—most allies align with multiple causes. In this context, a trans ally is a cisgender person who supports and uplifts the transgender community.

There is no "right" way to be an ally. The most important benchmark for a trans ally is to constantly grow in their understanding of the transgender experience.

Here are some general tips to help you in your journey to becoming an ally for transgender individuals:

- Unless you are transgender, you will never fully understand what it is like to be transgender. Thus, whenever it is safe to do so, take the chance to amplify the voices of transgender individuals rather than speak on behalf of them.

- Advocate for more inclusivity in your everyday life. Notice and speak out against strict gender markers on government-issued IDs, limited access to gender-neutral bathrooms and other policies that harm transgender individuals.

- Be gentle with yourself. There is no perfect ally. We all make mistakes, especially when it comes to nuances in culture and policy. Don't be afraid to acknowledge and apologize for any missteps and promptly move on.

- Make it known that you are a safe space for transgender individuals. You can do this by wearing a pin of the trans flag or LGBTQIA+ flag, attending rallies for transgender rights or volunteering at local LGBTQIA+ centers. No matter what your comfort level is, try to find a way to show support and care for your transgender peers.

For more best practices for trans allyship, check out this document from the National Center for Transgender Equality.

Commentary