An American History of Period Products

The global menstrual market is expected to grow to $27.7 billion by 2025, according to Markets and Markets. But the history of these products in the United States is a rocky one, partly due to the discomfort that stems from the supposed taboo of periods. The word "taboo" even comes from the Polynesian term "tapu," which was often spoken in reference to menstruation.

Still, it's a story worth telling. Ghosts of periods past have managed to permeate products currently being used. It's important to know what's changed, and how the zeitgeist surrounding periods has affected these transformations.

Before the 1800s

Before modern-day products were invented, many women used cotton or sheep's wool as a sort of DIY pad, according to Lesley Smith's 2006 article, "Menstruation: Curse or Blessing?" published in the Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care. Rags were often stuffed into underwear, which led to the term "on the rag" becoming slang for menstruation.

Native American women often used moss for pads, which wound up inspiring menstrual products well into the 20th century.

"One of the most interesting [products] was the use of sphagnum moss as a disposable absorbent pad [which] was derived from the material native women used to line their papoose-carrying devices," said David Linton, professor emeritus at Marymount Manhattan College in New York City and board member of the Society for Menstrual Cycle Research.

The 1800s to the 1900s

The 19th century was a time of somewhat shaky development. A notable product in the 1850s was the sanitary apron, a rubber apron with a strip that ran between the legs. It was more practical than previous period methods but far from perfect.

"They were heavy and stinky. It could not have been comfortable," said Sharra Vostral, associate professor of history at Purdue University.

Disposable pads were also developed during this time. The first ones to hit the market were Johnson & Johnson's Lister's Towels in 1897. They were made from (supposedly) antiseptic gauze and cotton, materials that had already been included in maternity kits to absorb postpartum blood.

Unfortunately, because of tight advertising restrictions and the stigma still surrounding periods, "they were not well received," explained London's Old Operating Theatre Museum, which houses collections of historical medical supplies. "It was simply the case that women were too embarrassed to be seen purchasing such items."

The 1900s to the 1950s

During World War I, nurses realized they could use cellulose war bandages as sanitary napkins, as the material was more absorbent than cloth. By 1921, the cellulose Kotex sanitary napkin had become the first successfully mass-marketed pad. Women were now able to go to department stores, take a box of Kotex and discreetly leave a nickel on the store counter.

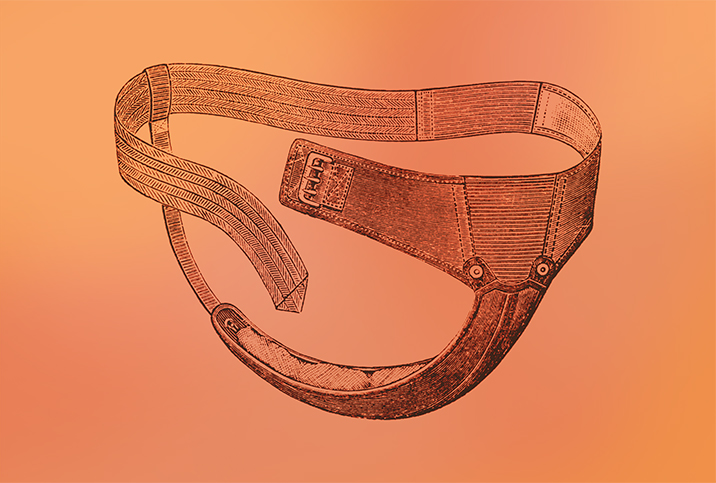

Johnson & Johnson also found more success as they rebranded Lister's Towels as "Nupak," with packaging that didn't allude to what the product was. However, pads weren't self-adhesive yet, so both products had to be attached to a sanitary belt (a somewhat similar contraption to the sanitary apron) with hooks or safety pins.

Another product developed during this century was, surprisingly, the menstrual cup, made from materials such as aluminum and vulcanized rubber. It was initially patented in 1867 by S.L. Hockert, but it was actress Leona Chalmers who branded them as "Tassettes" and brought them to the market in the 1930s.

But unlike modern times, this cup didn't find much popularity due to the messiness of the insertion process.

"It takes some practice to be able to remove them without spilling the blood," stated Lara Freidenfelds, author of "The Modern Period: Menstruation in Twentieth-Century America." "People found that extremely awkward."

Therefore, the cup was beaten out by the development of tampons in 1931. Earle Haas, who would later invent the diaphragm, made the product similar to our modern tampons, complete with an applicator. Kotex didn't think tampons could work and passed on them, but in 1934, Gertrude Tendrich bought the patent and officially founded Tampax.

Tampons were sold with the promise that they offered more freedom since they weren't as cumbersome as other products. However, they were generally advertised only to married women, due to the myth that inserting a tampon meant someone was no longer a virgin. While products were developing in terms of functionality, the conversations surrounding them were still limited.

The 1950s to the 2000s

As stigma surrounded tampons, pads continued to be the focus of most innovation. One of the biggest leaps came in 1956, when Mary Kenner, an African American inventor, created the first adhesive sanitary belt that would secure the pad in place. Unfortunately, racial discrimination led to Kenner's product being continually dismissed, and another company, Stayfree, was able to overtake Kenner in the self-adhesive market in 1969. Granted, Stayfree's adhesive pads no longer used the menstrual belt, and belts disappeared altogether by the 1980s.

Despite persistent stigma, around 70 percent of women used tampons during this time frame, according to Vostral. There were more strides forward, such as the brand Pursette releasing a pre-lubricated tampon, which helped combat the idea that only married women could use them.

However, not all innovations were safe. In 1975, the now-infamous brand Rely released a series of tampons made from polyester and carboxymethyl cellulose. The materials were super-absorbent, but they also festered the bacteria staphylococcus aureus, which left women vulnerable to toxic shock syndrome (TSS). From 1979 to 1996, over 5,000 cases of TSS were documented by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. While it's the bacteria, not necessarily tampons, that causes TSS, the Rely situation led many women to question their use of the product.

Even free bleeding without the use of any products, or "technologies of passing," as Vostral calls them, began to be embraced through the second and third waves of feminism, as many women refused to hide their body's natural cycle. This lessening of menstrual secrecy led to the word "period" finally being spoken on TV by actress Courteney Cox in a 1985 Tampax commercial. However, blue liquid and euphemisms were still used in advertisements to avoid the obvious, a strategy that continues even today.

The present and the future

Due to a growing social consciousness around sustainability, reusable cloth pads are on the rise. Similarly, the menstrual cup, which can now be made from silicone and latex, is more popular than ever before.

"The reason a variety of period products is important is because everyone's bodies and needs are different," explained Sara Twogood, M.D., a board-certified OB-GYN in Los Angeles, as well as co-founder of Female Health Education and the online magazine Female Health Collective.

Despite this greater variety and accessibility, the industry still has a lot of growing room left, as does the conversation surrounding periods themselves. Discretion is still seemingly prioritized above all else.

"Any products that shame period bleeding, including using fragrances to cover the 'period smell,' are taking us a step back," Twogood said.

Ultimately, shame-free education is necessary for period technology to develop, she added.

"Education and understanding how the female body works empowers people to try new products and ways to improve their lives," Twogood said.