Disease or Disorder: Temporal Lobe Epilepsy

Among neurological conditions, epilepsy is one of the most frequently diagnosed, affecting more than 3 million adults and about half a million children in the United States alone. Despite its prevalence, epilepsy is often misunderstood, which is unsurprising given the frequent updates in how central nervous system (CNS) disorders are classified and defined. One of the most common misconceptions is that it's a singular condition—there are many types of CNS disorders, categories of epilepsy and numerous types of seizures.

The epilepsy diagnosis is dependent on the number and type of seizures, where the seizure activity originates in the brain, physical manifestations, and the level of awareness a person maintains during a seizure. For example, temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) begins in the temporal lobes of the brain and involves various symptomatology and levels of awareness.

I was diagnosed with TLE seven years ago, and since then my view of epilepsy has irrevocably changed.

What exactly is TLE?

Temporal lobe epilepsy is a disorder resulting in recurrent seizures originating in the temporal lobes, which are located on both sides of the brain at about the level of the ears. These lobes are responsible for many important functions, such as sensory processing (auditory and visual), memory, language, learning and emotions.

The majority of TLE cases—including mine—result from unknown causes, but risk factors include early traumatic brain injuries (TBIs), brain tumors, genetics, infection and inflammatory conditions and other temporal lobe damage.

"In children, 70 percent of cases begin before age 3," said William Gaillard, an M.D. at Children's National Hospital in Washington, D.C.. "The average age of adolescent-onset is 14 years old, while adults are between 60-65 when tumors and dementia come in."

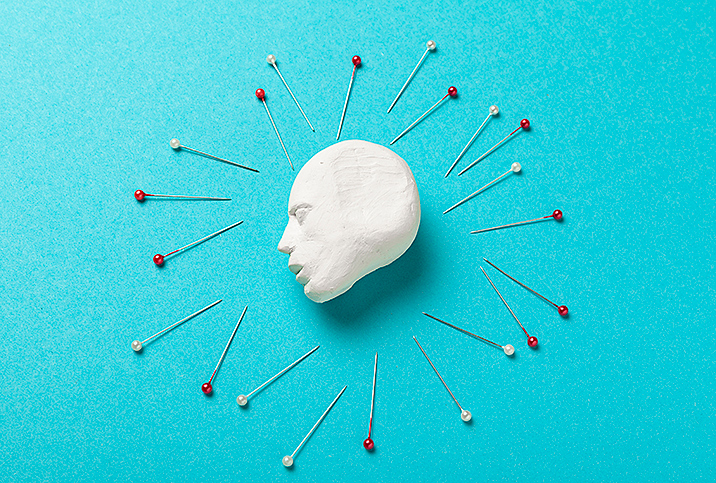

A seizure is caused by abnormal electrical activity in the brain, and people with epilepsy suffer them chronically. There are more than 30 types of seizures, but they fit into three classifications: focal onset, generalized onset and unknown onset. About 60 percent of people with focal epilepsy have temporal lobe epilepsy, where seizures start in one temporal lobe in the brain and progress to the other.

A seizure is caused by abnormal electrical activity in the brain, and people with epilepsy suffer them chronically.

Seizures affecting both halves of the brain are called generalized; these are the convulsive episodes most typically associated with epilepsy. It is possible for folks with TLE to experience generalized seizures, which can lead to the discovery of neurological disturbances.

Focal seizures are categorized into focal aware seizures and focal impaired awareness seizures. Both are brief, lasting no more than two minutes. During a focal aware seizure, the person remains awake, aware of themselves and their surroundings, whereas in a focal impaired awareness seizure consciousness is compromised.

For both focal and generalized seizures, people typically experience a postictal state, which occurs when a seizure ends and continues until the person returns to normal. Depending on the type and severity of the seizure, this period can last from seconds to days. Symptoms of exhaustion, weakness and memory loss are frequent—epileptics rarely remember the time during and after a seizure.

If the seizure was generalized, the risk for harm is high. Head trauma, bone injuries and bitten tongues are not uncommon. As a point of reference, I often bite my tongue to the point of bleeding and scarring during a seizure. Additionally, emotional and mental disturbances have been reported during generalized seizures, including agitation, confusion and verbal impairments.

My life with TLE

Over the years, I've experienced both focal and generalized seizures. Prior to my diagnosis, I brushed off my focal seizures as bizarre occurrences, which I thought little of because I've had them my entire life without knowing each was a sure sign of temporal lobe epilepsy.

Here are some of my own strange experiences:

- Feelings of déjà vu

- Speech incomprehension

- Memory impairments

- Unresponsive staring/daydreaming

- Nausea

- Olfactory and gustatory hallucinations

- Unprovoked anger and fear

- Hyperreal, dreamlike vision

My generalized seizures have been sporadic. The first occurred when I was 17 years old, without a definitive cause. My second seizure, also seemingly unprovoked, came at age 20. Then, I made a neurologist appointment, but before I could attend I had another episode that progressed into status epilepticus, defined as a seizure lasting longer than five minutes, which is a medical emergency that could lead to permanent brain damage. I seized more than a dozen times in a row and had to be put into a drug-induced coma to stop them.

Despite the massive fit, my brain scans were normal and my TLE diagnosis wasn't confirmed until I received results from a 48-hour electroencephalogram (EEG). I tried several medications unsuccessfully before finally landing on lamotrigine, which helps keep my seizures at bay; I am very fortunate, as one-third of people with TLE are drug-resistant.

Aside from extreme fatigue, lamotrigine doesn't give me any other adverse side effects. However, many epileptics report adverse reactions to antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) including rashes, headaches, insomnia, depression and sexual dysfunctions—almost a third of men have some type of erectile dysfunction (ED), and women often experience painful intercourse and vaginal spasms.

Needless to say, because of this, people with TLE could struggle with relationships and sex.

Diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis

A TLE diagnosis necessitates brain examinations, with the first step being an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan to check whether anatomical abnormalities, infectious/inflammatory processes or neoplastic processes (tumors) could be the cause of the disease, although they may not necessarily be present. The next stage would be to have an EEG during which electrodes are attached to the head to measure specific electrical activity in the brain—this test is crucial for determining where, when and for how long seizure activity occurs.

Once TLE has been established, a neurologist will draft a treatment plan, the first choice will probably be to prescribe antiepileptic drugs.

"If the MRI is clear, try medication first," Gaillard said. "After two medications you should think about epilepsy surgery, because after that there's a 2 to 8 percent chance of others working."

If medicine is unsuccessful, a temporal lobectomy may be performed to surgically remove the region where seizures begin.

"If there's a correlation to explain the epilepsy, surgery is first," he explained. "Now we see things that wouldn't have been operable in the past."

While there is no cure for TLE, management is possible.

Alternatively, there are implantable devices using deep brain stimulation (DBS) to reduce seizure activity or even halt one once it starts. Aside from using caution against TBIs, there are no preventative measures for TLE.

"Do not be complacent, the goal should be seizure-free," Gaillard continued. "Try to have some common sense of safety, but it's also important to live your life and not be intoxicated by your medications."

The best thing to do is to monitor your seizures and adhere to a treatment plan, as every case is different. Avoiding common seizure triggers is a good proactive approach and Gaillard strongly emphasized getting adequate sleep.

While there is no cure for TLE, management is possible. Consult with your neurologist if you have a seizure or before making any changes to your treatment plan. Tell people around you about seizure first aid so they can help during an emergency and take precautions concerning known seizure triggers. If you are on AEDs, check for any drug interactions, including over-the-counter medication, vitamins and supplements, and double check your dosage amount with your doctor.

Most importantly, remember you are not alone—there are abundant resources geared towards epilepsy, and you can have a full life in spite of adversity.