How 'Strip Down, Rise Up' Fails Strippers

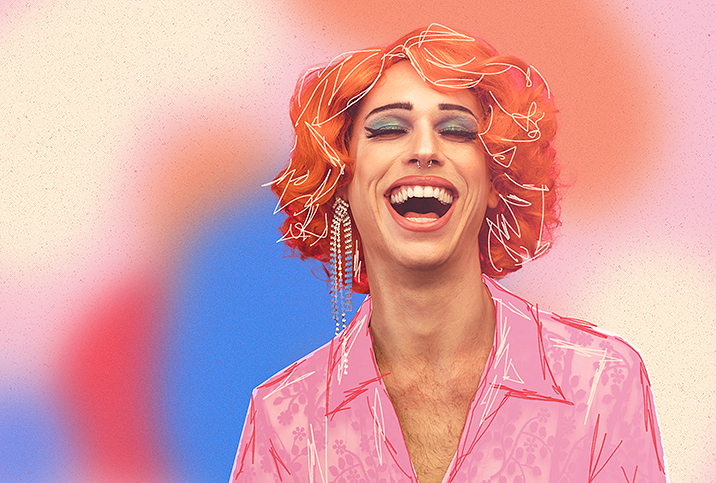

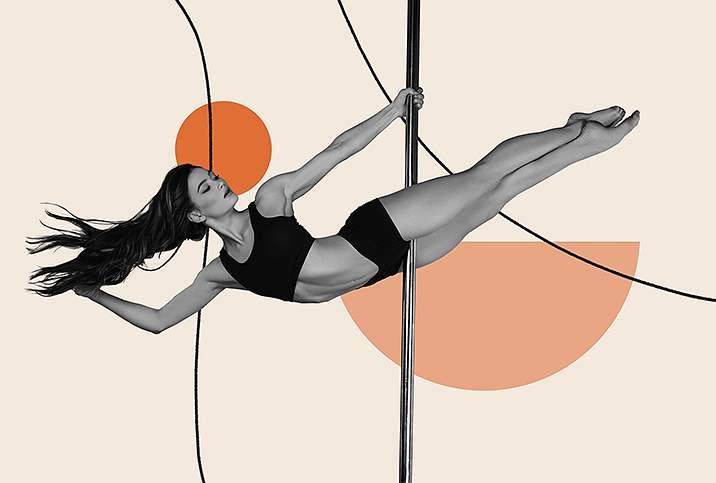

In the Netflix documentary "Strip Down, Rise Up," actress Sheila Kelley is on a mission to empower women through a "feminine-lifestyle practice." In less woo-woo terms, and more specifically, this means pole dancing at Kelley's national chain of workout studios, S Factor.

S Factor repackages pole dancing for a predominantly white, upper-class clientele, with the buzzworthy selling point of "healing benefits."

Both the film and the pole-fitness industry's efforts to package the art form in this way raises the question: When we commodify an art form born from strip clubs and tailor it to meet non–strip club needs, who suffers and who benefits?

A journey to wholeness?

With the conviction of a cult leader, Kelley shepherds women on a journey to "wholeness" through pole dancing. Kelley is quick to capitalize on the trauma many of the women express in class. However, Kelley doesn't have the credentials to discuss trauma—she's not a therapist, though she did play a role on "The Good Doctor." Rather, Kelley performs what she calls "body whispering" for her students, coaxing them to tap into their erotic power while offering intuitive readings as she hovers over their bodies.

At one point in the film, Kelley brings a triad of "heightened-conscience men" into a dimly lit studio for the women to confront, hug or cry at. Kelley fails to provide a metric for men having "heightened conscience," and subtly juxtaposes the difference between dancing for these men, who she deems "safe," versus men in a strip club—an action she refers to as dancing for the critical male gaze, thus not on-brand with her notions of feminine empowerment.

Exclusionary gendered messages frequently occur throughout the film, as when Kelley reprimands a woman for being overly masculine, critiquing her for "protecting herself with a masculine body."

Myopic, heteronormative views of gender and retraumatization aren't the only problematic parts of Kelley's pole journeys depicted in the film, directed by Michèle Ohayon. Despite the documentary's name, Kelley fails to include those who made pole dancing popular: adult entertainers—specifically, strippers. She doesn't pay homage to this lineage once or give a stripper or current sex worker a voice in the film.

When we commodify an art form born from strip clubs and tailor it to meet non–strip club needs, who suffers and who benefits?

Instead, she denigrates them.

"The second you say 'pole dancing,' you immediately think where men go to smoke cigars, drink and women do lap dances for money," she says in the film.

Kelley fails to give strippers any autonomy here, instead deciding to promote the notion that the "men are paying" and strippers dance for them. Kelley insinuates more troublesome polarities when she juxtaposes pole fitness against strip clubs throughout the film. Pole dancing at S Factor is empowered; dancing at a strip club is not. Strippers dance for the male gaze; S Factor students dance for themselves.

Some strippers publicly took issue with the film. For instance, in an article published on Buzzfeed, stripper April Haze explained that her own experiences are much more nuanced than the black-and-white realities outlined by Kelley in the film.

"I use the male gaze to empower myself and reclaim my sexuality," Haze said. "You can go ahead and do that by yourself in a room with no mirrors. I'm going to go ahead and do it onstage."

Stripper erasure is everywhere

"Strip Down, Rise Up" is just one example of how stripper erasure works, but it's speckled throughout the entire pole-fitness industry. Disparities between the use of the pole for labor versus fitness always end with the same result: divorcing pole dance from its roots and hurting strippers.

Pole dancing for fitness isn't the issue—or even the point. Rather, it's that pole-fitness enthusiasts often dismiss these origins entirely. This detachment contributes to stigma, hurting the fight for strippers' labor rights.

And it's not just structural—it's social as well. In 2016, a pole-fitness dancer started the hashtag #notastripper on Instagram, which speaks to how ashamed gym-goers are to acknowledge pole dance's strip club roots. In the film, a pole dancer exclaims, "I want to live in a world where you say you're a pole dancer, and the first thing someone says isn't, 'Are you a stripper?'"

Disparities between the use of the pole for labor versus fitness always end with the same result: divorcing pole dance from its roots and hurting strippers.

That last statement could be read as an example of whorephobia, or, "The hatred of, oppression of, violence toward and discrimination against sex workers; and by extension derision or disgust toward activities or attire related to sex work." Whorephobia extenuates stigma, and stigma leads to violence.

The world of pole fitness was quick to capitalize on pole dancing and rarely acknowledges its founders. There is now a national competition devoted entirely to the sport held by the Pole Sport Organization (PSO). On PSO's website, there is not one mention of the history of pole dance. There is, however, a category that pokes fun at stripper erasure, called Shadowbanned.

The term "shadowbanned" refers to Instagram hiding images that include "photos, videos, and some digitally-created content that show sexual intercourse, genitals, and close-ups of fully-nude buttocks."

For strippers, shadowbanning and FOSTA-SESTA impact income and their livelihood. Strippers use social media to promote their work, share their whereabouts with loyal clients and gain access to new clients, and as you can imagine, they frequently face shadowbanned posts and deleted accounts.

When strippers' accounts are shadowbanned, it is detrimental to their ability to promote their livelihood.

Like shadowbanning, FOSTA-SESTA, two laws passed by Trump, aims to crack down on sex trafficking and adversely equates sex workers doing consensual sex work with sex traffickers. FOSTA-SESTA made it harder for sex workers to find work, vet clients and post schedules because the laws specifically target online spaces.

PSO responded to shadowbanning with the following description for a performance category:

"SHADOWBANNED: Is your style getting you shadowbanned on Instagram? Bring it here. The only rule is the nastier, the better. Get dirty with it on the pole and be classy or trashy, we'll take it all."

When strippers' accounts are shadowbanned, it is detrimental to their ability to promote their livelihood. When pole-fitness enthusiasts are shadowbanned, it impacts their ability to promote their talents. These two experiences of being shadowbanned are not equal, due to the gleaming privilege of pole dancing as a hobby rather than for labor.

By failing to recognize this critical difference, PSO neglects to acknowledge the impact of stripper erasure on the whole, digging a deeper ditch for those in the profession.

Acknowledge the roots

The pandemic heightened the lack of protections for strippers through sex-work-exclusionary COVID-19 loans, higher competition for online work and the closure of strip clubs, leading to reduced or no income.

Pole-fitness enthusiasts have a responsibility to strippers because pole dance was theirs first. When you sever pole dancing from stripping, it creates a capital that leaves founders in the dust. If we're ever to truly support a stripper's right to make a living, respecting their work as theirs is a good place to start.