Prostate Cancer Detection Gains a New Imaging Technique: PSMA PET Scan

"Knowing is half the battle," an old adage says.

When fighting cancer, knowing where to find the lesion may constitute even more than half the battle.

Pinpointing the exact location of cancerous cells can change a person's life. That's especially true for prostate cancer patients who have a recurrence after treatment or whose cancer may have spread.

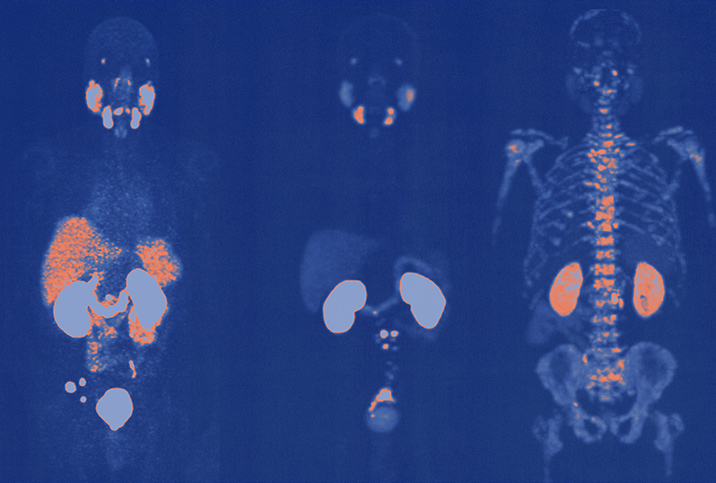

That's why the PSMA PET (prostate-specific membrane antigen, positron emission tomography) scan has healthcare providers so optimistic. This innovative and highly accurate new technique for prostate cancer detection is moving toward wider implementation.

We'll look at how PSMA PET works, how it differs from older imaging techniques and why it's so groundbreaking in the world of prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Imaging then and now

"When we talk about imaging for prostate cancer, we talk about two buckets," said Peter Reisz, M.D., a urologic oncologist with Lehigh Valley Physician Group in Pennsylvania. "One, where we're doing pretreatment staging for a newly diagnosed patient to make sure they don't have metastatic disease. And two, those who have a recurrence or PSA [prostate-specific antigen] recurrence after treatment, and in looking for the source of that recurrence."

Traditional imaging techniques for most types of cancer include an array of scans.

CT scans

A computed tomography (CT) scan uses software linked to X-rays to get 3D images of soft tissue, bones and blood vessels.

Bone scan

Changes in your bone structures may indicate cancer has spread, so this scan looks for bone turnover.

MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used more often in conjunction with biopsies in prostate cancer diagnosis. MRI scans can better target suspicious lumps and nodules and spot enlarged lymph nodes.

PET scan

A positron emission tomography (PET) scan uses injectable radioactive tracers attached to sugar molecules that show unusual metabolic activity indicative of cancer.

PSMA PET takes imaging to the next level

PET scans have long been used for imaging a number of cancer types. Until recently, though, they weren't usually part of the imaging toolkit for prostate cancer.

It wasn't until 2020 that the Food and Drug Administration approved a drug that was tagged to prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA), a protein found on the surface of prostate cells. The technology uses PET scans to identify those cells.

"PET scans work great when you have a great target, but you have to develop a specific target," said Brian K. McNeil, M.D., the chief of urology at the University Hospital of Brooklyn in New York City. "It's taken us some time to figure out what makes a great target to scan for prostate cancer. And so with PSMA, the medical community is like, 'OK! This is our target. Let's use it.'"

Taking the guesswork out of it

Understand that prior to the advent of the PSMA PET scan, imaging for prostate cancer spread was largely based on educated guesses. When prostate cancer spreads, it commonly follows a specific path, heading directly for the pelvic lymph nodes and then the bones. But imaging these areas with CT scans or an MRI usually can't reveal definitively if there's cancer—only that the structure has changed.

"What we're looking for with a CT scan is enlarged lymph nodes in the pelvis because that's the first place prostate cancer usually spreads," Reisz said. "If there were an enlarged lymph node on a CT scan, that could be a sign there's metastatic prostate cancer in that lymph node. But this is strictly based on size on a CT scan, which is very nonspecific. You could have enlarged lymph nodes for a wide variety of reasons."

The same principle applies with the MRI, although it offers a bit better imaging than a CT scan.

Getting to the root of the problem

Not only is the PSMA PET scan aimed squarely at prostate cells, it's also targeted at a protein found in much higher concentrations on prostate cancer cells.

"It's not just a general sugar molecule that gets taken up," Reisz said. "It attaches specifically to this prostate-specific membrane antigen, which is a protein that sits on the membrane of prostate cells. You can almost say it's specific for prostate cancer cells because prostate cancer cells express this protein at much higher levels than regular prostate cells, on the order of 100 to 1,000 times higher."

Another way the PSMA PET scan changes the game is it allows clinicians much more certainty in diagnosing the parameters of a patient's recurrence of cancer if they show elevated PSA levels after treatment. PSA is a protein produced by both normal and cancerous prostate cells, and elevated levels in the blood can possibly indicate the presence of cancer. Studies show it takes only a tiny amount of cancer cells in, say, the lymph nodes or bones to light up the radiotracers on a scan.

"The PSMA imaging helps us to determine if they truly have localized disease, and two, to detect the metastatic or recurrent lesion," Reisz said. "If it's present in the pelvis, or even in the prostate after radiation therapy—since we leave the prostate in the body after radiation therapy—we can then plan our salvage therapies."

Not only that, they can see exactly where those cells are with a remarkable degree of accuracy.

The next phase

The PSMA PET scan is a tool that is becoming more and more accessible. Currently, a limited number of sites around the country have the tools and training to use the technology, but this number is rapidly changing, since PSMA PET was just approved for use in 2020.

"Even in the two years of my fellowship, patients were having a hard time getting these PSMA scans at the beginning of my fellowship," Reisz said. "By the end, we were ordering it for—I don't want to say everyone—a very large percentage of patients with higher risk disease and, specifically, recurrent disease."

American Urological Association (AUA) guidelines stipulate that the PSMA PET scan is appropriate for men with suspected recurrent disease but not at the outset of their original diagnosis.

Many healthcare professionals hope the recommendations change soon.

"If you're a person newly diagnosed with high-risk prostate cancer, wouldn't you want to know if it's maybe involving the lymph nodes or the bones, even if you may not be able to see it with other modalities?" McNeil said. "So even though that's not an official recommendation now per the AUA, I think that's something we may reconsider in the future as the PSMA becomes more available."